A War Zone Pediatrician on What Comes After the Horrors of a Gaza Emergency Room

Dr. Seema Jilani Reckons with the Hypocrisy of Western Liberal Institutions

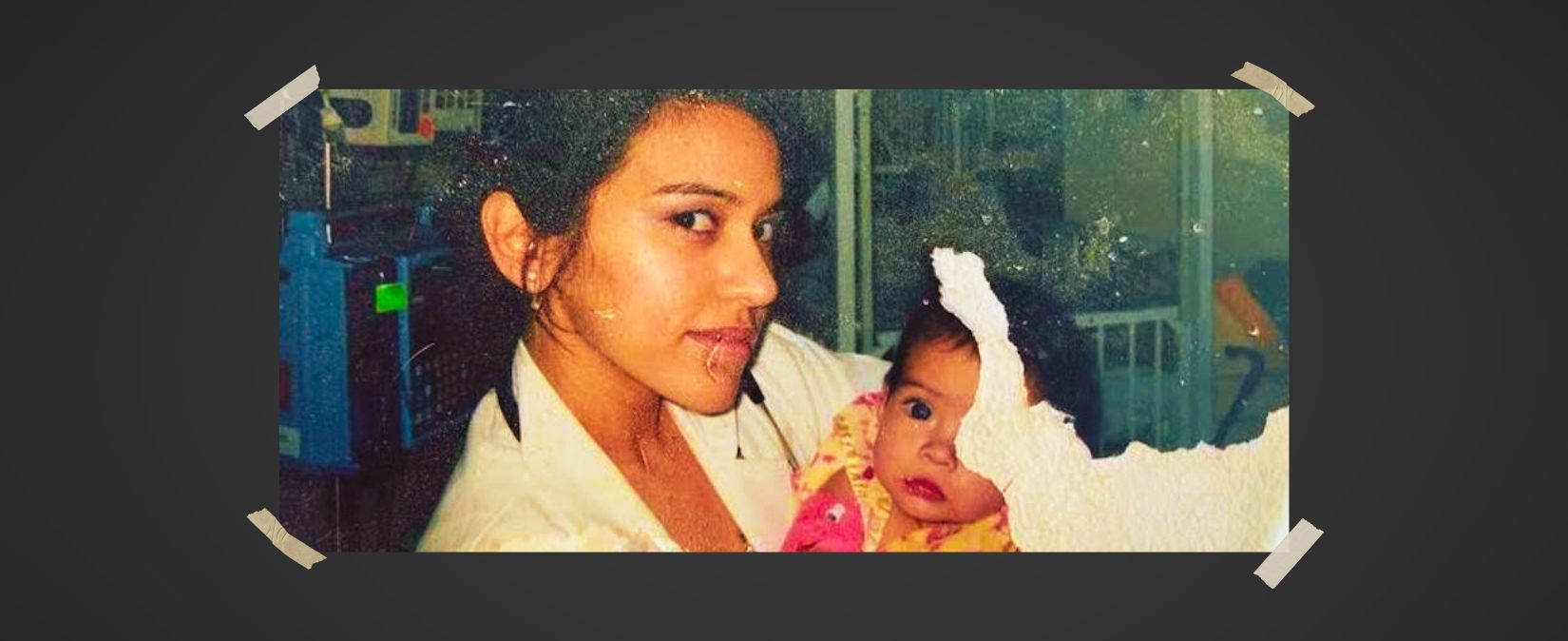

Image above: Dr. Jilani with one of her pediatric cancer patients. The photo was damaged in a 2020 blast in Beirut.

* * *

I scroll aimlessly on my phone, stumbling onto video footage of Shaban Al-Dalou, a 19-year-old man engulfed in flames outside Al-Aqsa Hospital in Gaza. I immediately recognize the hospital and nearby flimsy tents crammed with displaced families. I had worked as a doctor on those very grounds, which became a makeshift village with its own subculture.

A barber had set up shop outside the clinic, promising a sharp shave alongside patients needing wound care. The coffee man walked the alleys with scalding cardamom qahwa, the ladle jangling as I tiptoed over sewage to get to my emergency room shift. The video, in which Al-Dalou is burned alive while clutching his IV tubing, left me utterly devastated, and wondering who else might have succumbed to the fire.

In my time working as a pediatrician in Gaza, I saw starving babies gasping for air and reaching for their mothers, who were buried under rubble. I treated an entire family who had sustained third degree burns. Eyes blistered shut. Children’s genitalia scorched and disfigured from bombardment.

In trying to fathom the unfathomable scenes of human tragedy in Gaza, I have turned to women whom I knew would not offer performative allyship or suggest moderating my tone of anger; nor would they diminish my tears or silence my voice as so many do. They have, not coincidentally, also been prominent women whose identities have been sculpted by Western colonialism. I have leaned on Fatima Bhutto, a writer and novelist who hails from one of South Asia’s most intriguing political dynasties, the Bhutto family of Pakistan. I have confided in Najla Said, actor, playwright and daughter of the Palestinian American intellectual Edward Said. His work implored the West to leave behind exotified images of Asia and the Middle East, seeing them as mirages which exist only to justify Western colonial aspirations. Said had a transformative influence on the humanities with his landmark book, Orientalism, which upended the prism through which postcolonialism would be studied.

I chose to leave my seven-year-old daughter behind to treat war-wounded children who resembled her, except that their limbs hung by a thread of flesh and their bodies were charred black beyond recognition.

People like myself, Fatima, and Najla are daughters born of colonization. We have been forced to face a deep reckoning with the silencing of our voices on Gaza, enduring threats to our livelihood, our families, and even our own safety. Model minorities and children of refugees like us are the forgotten corollaries to dead empires. We are exotified, tokenized, sexualized, and lauded as consummate children of the diaspora.

One might find us on the covers of university brochures, a brown face to showcase diversity, but rarely are we allowed into boardrooms. Whether we are deployed into war zones, or dispatched to the fringes of society, we have worked relentlessly to hold institutions accountable for their failures. It is a grueling and often risky task, which few in elite circles dare to dabble in. When it comes to speaking on the issue of Palestine, though, our voices are routinely quashed. Our very humanity is placed under a microscope whenever we choose to raise our voices above the fray.

With trembling fingers, I texted them both after watching Al-Dalou ablaze. Fatima spoke to me on the phone from her home in London. I was still in my scrubs, post-night shift at the children’s hospital I work at in Houston. My night consisted of taking care of a teenager with leukemia, a child with sickle cell anemia admitted for severe pain crisis, and an adolescent who had tried to end her life. Fatima had just completed a marathon nursing session with her ravenous infant son. I hung my stethoscope up as her baby whimpered in the background. The soft coos transported me back to those wondrous early days with my own daughter.

The war in Gaza has taken its toll on us as mothers. I chose to leave my seven-year-old daughter behind to treat war-wounded children who resembled her, except that their limbs hung by a thread of flesh and their bodies were charred black beyond recognition. One of my patients in Gaza even shared the same name as my daughter. I once watched a fly drown in the blood of a one-year-old child whose limbs had been blown off. Fatima found herself between baby feeds, blown-out diapers, and night awakenings, watching the atrocities against Palestinians unfold in the palm of her hand.

Watching Gaza quite literally burn to death without so much as a collective sigh from those who are complicit, Fatima and I have never been more cognizant of the fact that we are, and always will be, on the outside. Tomorrow, it could be our children, we said to each other.

Those brown children in far off lands are as much ours as any others, and we had foolishly hoped others would recognize their innocence as well.

“It has been extraordinary to watch Western journalists talk about Israel’s pager attacks in Lebanon—which, by any definition of the word, was terrorism—with awe,” Fatima said. The attacks were largely framed as a spectacular feat of glorified warfare. The New York Times lauded it as Israel’s “Trojan Horse,” and praised Israel’s “tactical success” and “technical prowess.” The Associated Press called the operations “sophisticated, deadly attacks that targeted an extraordinary number of people.” Emily Harding, a veteran of the CIA and the US National Security Council, described the attack as an “intelligence bonanza.”

Both Fatima and I recalled one detail simultaneously. One of the pagers sat hinged on the waist of a father who was taking his ten-day-old son, Aiman, to his pediatrician for the newborn visit. As Aimon weighed in at about seven pounds on the doctor’s scale, his father’s pager sounded. When it detonated, shards of shrapnel darted through the examination room and blew the doctor to the corner. Metal pierced the father’s abdomen and two of his severed fingers lay scattered on the ground. Explosive debris lacerated Aiman’s face and left him with injuries, but he survived. The attacks killed at least 37 people—including two young children—and wounded thousands more.

I remember my first doctor’s visit with my baby girl. I had placed a dainty lavender floral headband in her hair. The pediatrician was so tender while she listened, ever so gently, to her heart, sweeping the hair from her forehead. That is the memory I wish for every new parent. Those brown children in far off lands are as much ours as any others, and we had foolishly hoped others would recognize their innocence as well.

Dr. Jilani examines a newborn baby in southern Syria in 2024 during the Assad regime’s “starve and siege” campaign. Working with the Syrian Emergency Task Force, she was the first pediatrician to see patients in the Rukban Camp.

Dr. Jilani examines a newborn baby in southern Syria in 2024 during the Assad regime’s “starve and siege” campaign. Working with the Syrian Emergency Task Force, she was the first pediatrician to see patients in the Rukban Camp.

Both Fatima and I have roots in Pakistan. I was born in New Orleans to Pakistani parents and was raised mostly overseas—in Saudi Arabia, England, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Venezuela—due to my father’s job as an oil and gas engineer. My family finally settled in Texas, home of Big Oil. My childhood was entrenched in the folklore of Western exceptionalism; assimilation was the only way for me to garner respect.

My cowboy boot-wearing father did not allow us to speak Urdu. Thankfully, my mother taught us in secret. My dad hung an American flag outside our home and diligently took it down when it rained so it would not soil. I had memorized more lyrics to Erykah Badu songs than verses of the Quran, and my work ethic would have been the envy of the pilgrims. I am America’s immigrant poster child: a child and grandchild of refugees who had vaulted continents and oceans in search of a better life for us, which allowed me to claw my way up the ranks to become a physician.

Fatima’s girlhood was spent in Damascus. She and family lived in Syria while her father was in exile during the military and fundamentalist regime of General Zia-ul-Haq in Pakistan. Her life did not include the fantasy of American freedom. She is the daughter of politician Murtaza Bhutto, niece of former Pakistani Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, and granddaughter of former Prime Minister and President of Pakistan Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. “My father’s father had been toppled in a CIA-backed coup. The West’s dark side was always present for me. In Pakistan, thousands were killed, arrested, and public floggings occurred at the behest of an American- and British-backed dictator. We never had a romance about what the West represents.”

When I speak of the atrocities I witnessed in Gaza, I must qualify my words with false neutralities and the impotence of the passive voice; both serve only to exonerate the aggressor of their crimes.

Fatima’s book, Songs of Blood and Sword, published in 2010, is a captivating novel that traces one of South Asia’s most enigmatic political families—her own. She was lauded for her tenacity and bravery in speaking truth to power in Pakistan, holding to account some of Pakistan’s highest-ranking military and government officials. She even alluded to her aunt and uncle being responsible for the murder of her father, who stood to be the most daunting threat to Benazir Bhutto and Asif Ali Zardari’s reign.

“I spent many years writing about power and corruption in Pakistan. My book accused a sitting Prime Minister of murder, and I was living in Pakistan at the time. That did not feel as risky to speak about as it does to talk about Gaza,” Fatima said.

The muzzling can be authoritative and naked, or nestled in the recesses of polite society. Either way, the effect it has on people in the diaspora, whose life has been shaped by the brutality of imperialism, is menacing. After working in Gaza, one observation I made in interviews with media outlets was that I had expected the majority of the wounded to be young men. However, the reality in Gaza was that my patients were disproportionately children, unlike any other conflict zone I had ever worked in.

I was explicitly directed by my NGO leadership not to use this phrasing; they were afraid that it made it seem like my intention in going to Gaza was to treat Hamas fighters. Clearly, as a pediatrician, this didn’t even make sense. Later, when Jewish Voices for Peace asked me to participate in a webinar, my NGO leadership decided it was too political an organization to collaborate with on the topic of Gaza.

“It operates very forcefully and it operates in the silences as well. You understand that to say certain things means you will not get certain jobs.” said Fatima.

The echo chamber of elite Western media stands as a chilling fortification of colonial condescension towards brown people. Platforming only those who hail from generational wealth and privilege eats away at our collective morality. Perhaps the most formidable mechanism of this is self-censorship, which reflects the internalized grip colonialism has over our psyche. When I speak of the atrocities I witnessed in Gaza, I must qualify my words with false neutralities and the impotence of the passive voice; both serve only to exonerate the aggressor of their crimes. In our media landscape, Palestinian children are routinely “found dead,” whereas Ukrainian children are brutally “killed” by Russian aggressors. When the Israeli military releases a statement and prominent American newspapers serve as its stenographers, the erasure of Palestinian perspectives etches into the historical record.

The war in the Gaza Strip has laid bare many uncomfortable truths, none of which are foreign to those of us who grew up in the shadow of colonial powers and the wars and coups they instigated.

As brown women in particular, we are relegated to two phenotypes: eroticized and worthy of being (briefly) heard, or intellectually honest but dismissed. This is a relic of legacy media, which helicopters Western journalists into war zones so that they can depict us as caricatures palatable to Western audiences: mute and in burqas, or feisty and fetishized, pleading for our humanity.

The war in the Gaza Strip has laid bare many uncomfortable truths, none of which are foreign to those of us who grew up in the shadow of colonial powers and the wars and coups they instigated. Compassion for Palestinian children has been subsumed by rage and hatred. Antisemitism and Islamophobia are both on the rise, but the epithet of “antisemite” has been used to demonize critical voices, mutilate the first draft of history, and decide whose perspective commands respect in the halls of power. Voices like mine have been ignored.

The establishment has even resorted to intimidating us into silence, often calling the veracity of eyewitness accounts, including mine, into question. After returning from Gaza, I spoke publicly throughout the spring of 2024 about what I bore witness to—mostly the nightmarish injuries children endured from Israeli bombardment. My work—which has been featured in The New York Times, NPR, PBS News Hour, and The New Yorker—has resulted in death and rape threats, career instability, and a profound fear for my safety which continues to the present.

Last November, I was invited to speak alongside Arwa Damon, former CNN Senior International Correspondent, by the Columbia Human Rights Initiative Asylum Clinic, an organization of medical students and faculty at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons which is committed to a human rights-centered approach to medicine. The subject of our panel discussion was healthcare in Gaza and the audience was made up of medical students from all over New York City. The organizers informed me of the risk of the lecture being canceled at the last minute. The week before, a similar lecture had been canceled without a known cause.

As speakers, we had asked permission for our own guests to attend; those requests were denied. The guests who were not allowed to attend our talk had one common affiliation: being members of the media or in the communications fieldofficers. Our lecture also required extra security. The very notion of needing additional police officers for security because we were discussing the “G” word—Gaza—is emblematic of the muzzle. That it was occurring at the storied home of Edward Said would have been comical if it didn’t feel so dystopian.

Recently, Najla Said and I sat on the stoop of an Upper West Side brownstone, coffees in hand, watching strollers, nannies, and women zoom past us en route to spinning class. Najla wore a newsboy cap over her deep brown hair, which cascaded down her shoulders. Najla has searing auburn eyes with eyelashes almost to her cheeks. Chic, even when dressed in simple black leggings and a coat, she clearly inherited her father’s daring charisma. She told me how her father’s office, which used to sit in Columbia’s Hamilton Hall, was once fire-bombed, and how heartbreaking the past year has been, from losing friends and opportunities to worrying if her family in Lebanon is safe from Israeli bombardment.

“My father taught me the word ‘solidarity,’ while holding my hand, standing in front of Hamilton Hall. Columbia always stood by my father’s right to free speech. It was a wonderful institution.” she said, full of melancholy. “When I was a kid, I thought the word ‘campus’ meant playground because that’s where we went to play. When my dad took me to nursery, he would take me the long way so he could walk through the campus. I loved that campus. Now it’s closed off and unless you have a student ID you are not allowed there.”

The hurt in her voice gutted me. “If he were alive, he would be out there shaking his fist, like he always did,” she laughed. Najla is fully cognizant that this is not personal, but it doesn’t change the way it feels, like “a deliberate attempt to erase my dad, someone who was a bastion of knowledge, arguments, intellectualism, and someone who was pro-Palestinian.”

In early 2010, a then thirty-five-year-old Najla stepped on stage at the Fourth Street Theater for her first one-woman show, Palestine, a cathartic exploration of her complicated relationship with Palestine. Said hypnotized the audience with her personal tales of meeting Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, covertly kissing Jewish boys in her Upper West Side neighborhood, and wrestling with post-9/11 paranoia. The show ran for eight sold-out weeks and secured vital financial support from Daniel Barenboim, who, along with his friend and collaborator Edward Said, had sought to encourage conversations between Arabs and Israelis.

Palestine sustained a successful run with enthusiastic reviews and audiences keen on more. But that is where it ended. The play was never picked up by further investors, nor was it shown in other cities. As time went by, the phone calls dried up. For most other playwrights, the show’s triumph would have solidified Said’s stature as a promising star in New York’s theatrical ecosystem. Instead, any hopes of reviving her play in the future have come to a halt amid the current unsettling climate of discourse around Gaza.

Najla relayed to me how her father conscientiously made the choice not to politicize himself until he was highly regarded, fulfilling the tenets of the fairytale we had both bought into. To instigate change as someone from colonized lands, first, you must navigate the labyrinth the colonizer has laid out for you.

“When I attended Princeton, dad said, ‘You have to charm your way into these worlds, know the people, and work for change from there.’” For Najla, the rules of engagement changed the minute she flirted with wider success or had the audacity to stand against the war in Gaza.

The fabric of so much modern Western culture—academic, intellectual, scientific, and artistic—has been fashioned from the work of refugees and dissidents from oppressive regimes who made their homes here. Whether creatives who keep a society’s spirit afloat, doctors who garnered applause during the pandemic, or writers who fill the literary canon with its most fertile prose, our success is still so often dependent on how vocal we are in our critique of those in power.

I had steered my ambitions with agility throughout my career, making myself palatable with my American accent and my straightened hair, clawing up the ladder to the rarefied air of elite spaces where legacy admissions were the norm. I interviewed for medical school in the aftermath of 9/11, at the height of Islamophobic hysteria. From Chicago to Boston to New York, I was asked in interviews whether my father taught me how to make bombs, if I would wear a burqa when I became a doctor. For decades, I was just grateful to be allowed a seat at the table.

I have worked in conflict zones from Afghanistan to Ukraine, and even on refugee rescue boats adrift off the coast of Libya, but nothing could have prepared me for a Gaza emergency room.

Our parents, traumatized by war, crossed oceans to get us here, to the land of the free. Now each of us, in our own way, has been trying to find out who we really are: going back to war zones our parents fled, returning to offer solidarity, trying to feel some remnant of what might feel like home, neither here nor there, writing books about the legacy of Western backed coups that resulted in a father’s exile and eventual death, and representing Palestinian and Arab women in theater.

We have been searching for what we were promised. The naked hypocrisy around Gaza has torched that promise.

In the enduring images of Al-Dalou clutching to IV tubing, suffering from asphyxiation in a desperate attempt to escape the flames, I recognize something of myself. Perhaps he thought he would be protected, that he could rely on his proximity to a hallowed, sacrosanct building, a hospital. Our proximity to elite institutions of prestige did not save us any more than his proximity to a hospital did.

Dr. Jilani and her father, Airaj (Reg) Jilani. Airaj was born in India and then traveled by boat as a refugee to Pakistan during Partition, then immigrated to the UK, and the US, thereafter. He remains a proud Texan.

Dr. Jilani and her father, Airaj (Reg) Jilani. Airaj was born in India and then traveled by boat as a refugee to Pakistan during Partition, then immigrated to the UK, and the US, thereafter. He remains a proud Texan.

I have worked in conflict zones from Afghanistan to Ukraine, and even on refugee rescue boats adrift off the coast of Libya, but nothing could have prepared me for a Gaza emergency room. As I exited Rafah, my nose hair still tingled with the smell of the singed flesh of a young girl. Her face was molten and charred and her neck was crusted black as she cried out for her mother, who, we couldn’t bear to tell her yet, had been killed in an Israeli airstrike.

I had cradled the body of a Palestinian UNRWA staff member and whispered some words of comfort in his ear as he took his last, anguished breaths in my embrace. The near constant sounds of airstrikes near our guesthouse were deafening. I would spend nights trembling, watching tornadoes of smoke rise to the sky. But after two weeks working in a besieged Gaza hospital with Israeli forces closing in on us, I had made it out alive.

The ceaseless hum of the Israeli drones began to fade away as we sped out of the Gaza Strip and across the Sinai desert to safety. The jarring buzz of the drones—a constant reminder that our lives were always in peril—gave way to the husky voice of Egypt’s beloved singer Umm Kulthum coming from the speakers of our van. Working alongside Palestinian doctors, having closely coordinated with the UN, the World Health Organization, and the Israeli authorities, I helped design our medical team deployment into the Gaza Strip on a life-or-death pilot project for the International Rescue Committee to see if we could safely send doctors into one of the world’s most dangerous war zones.

Our IRC guesthouse was supposedly “deconflicted,” meaning that parties to war had agreed that its specific geographic coordinates were off limits from military air strikes. Shortly after I left the Gaza Strip, the guest house was bombed with a US weapon by the Israeli military, facts confirmed in a UNMAS investigation. The home had children staying there as well as our team, including international doctors, security staff, a team leader, and others who sustained injuries in the bombing. The Israeli government has since given no less than six different explanations as to why a deconflicted coordinate was attacked.

Within the IRC itself, some colleagues blamed me for the bombardment, insinuating that it happened because I spoke about the horrors in Gaza to the media, which drew widespread attention to our work. Those accusations haunt me. I have replayed the sequence of events in my head over and over to see if I was in any way responsible. Wracked with guilt, I relentlessly mapped out the timeline of my media engagements to see whether correlation could imply causation. But the only rational conclusion is that the responsible party is the Israeli military, the actual people who bombed the deconflicted IRC guesthouse. Any other explanation linked to my speaking out on Gaza serves only to intimidate and silence me, maintain the unquestioning innocence of the perpetrators, and absolve the Israeli military of a war crime.

I left Gaza several pounds lighter, with a shattered spirit and a suitcase full of crimson-stained scrubs. After washing the grime out of my hair in Cairo, I sat down at my computer to update my supervisors and discuss our plans to debrief David Miliband, the former former British Foreign Secretary and current President and CEO of the International Rescue Committee.

As senior advisor and organizer of the Gaza health mission, I expected the main debriefing duties would fall to me. The prospect of explaining our successful mission to Miliband was motivating. IRC leaders were already considering sending me to brief the National Security Council and discussing the possibility of meeting with then Vice President Kamala Harris. But my supervisors had other ideas. The briefing of Miliband, they told me, should be attended by one of the British doctors who worked with me in the Gaza hospital as well.

“Miliband needs to hear this in an Oxford accent,” one of my bosses told me in an online meeting with two of my superiors.

I was stunned. I have worked intermittently in the Middle East for twenty years, including in the West Bank, Gaza, Egypt, Lebanon, Syria, and elsewhere. When I advocated for women’s rights while working in Afghanistan in 2010, my voice mattered. I was praised in 2013 for putting a spotlight on draconian Pakistani Muslim extremism and bravely standing up against the Taliban’s regressive brand of Islam.

When I wrote in The New York Times about two young girls shot alongside Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai, or about survivors of the Srebrenica Genocide in Bosnia, or about treating patients on refugee rescue boats off the coast of Libya, I was heralded for taking a principled stance. When I speak of the horrors visited upon the people of Syria by the Assad regime or of those Russia perpetrated against the people of Ukraine, it is considered a righteous indignation. When my own daughter was injured in the Beirut blast of 2020 and I called for accountability from the Beirut government, my outrage was ensconced in morality.

Working with the Syrian Emergency Task Force, Dr. Jilani was the first pediatrician to enter the Rukban Camp and was flown in via US military Chinooks and C-130s, under Operation Syrian Oasis, to Al-Tanf Garrison in southern Syria.

Working with the Syrian Emergency Task Force, Dr. Jilani was the first pediatrician to enter the Rukban Camp and was flown in via US military Chinooks and C-130s, under Operation Syrian Oasis, to Al-Tanf Garrison in southern Syria.

I have had an entirely different reception when I try to talk about the basic indignities of undergoing a Cesarean section with no pain medication in a Gaza hospital under bombardment, or the reality of seeing the insides of a Palestinian toddler’s brain mashed on her scalp, her hair tangled with congealed blood. I can be trusted to care for an American child with a brain tumor, but not trusted to share what I saw with my own eyes in a Gaza Emergency Room. Even though I had designed and led the pioneering Gaza mission for IRC, I was explicitly prohibited from talking about Gaza at several speaking engagements by my boss, a progressive white woman.

Then, in a group meeting discussing our humanitarian action in Gaza, one of my colleagues announced that the IRC would be sending its “first program staff” into the Gaza Strip.

“I know you went into Gaza, Seema,” my colleague said on the group call, “but you don’t count because you went in as a doctor.”

You don’t count.

Immediately after hanging up from the meeting, I burst into tears. I thought I had counted when, shortly after exiting Gaza, I was invited to a private briefing of member states at the United Nations Security Council. As I was preparing my statement for the UN briefing, my boss reminded me I had the option of simply reading the statement online remotely instead of traveling to the United Nations in person. This, she said, was “for your own mental health.” I have held dying children in my arms for the better part of twenty years. There is nothing more corrosive to my mental health than to remain distant or quiet about violence committed against children. I remembered what Palestinians in Gaza explicitly asked of me: “When you leave, do not forget us. Tell our stories to anyone who will listen.”

In war, I said, we talk of the fall of cities. The Fall of Mosul. The Fall of Saigon. I asked when it became normalized to speak of the Fall of Hospitals.

Wearing an oversized suit in Manhattan, I sat in a room full of UN, MSF, and WHO representatives, as well as dozens of diplomats and their staff. I was the only woman of color in the room. I read my statement at this UN Security Council briefing, detailing my time in Gaza with pediatric patients, and marveling at how the rules of engagement for war have been altered to accommodate Israel. I told them that of all the war zones I’d worked in, I’d never seen the magnitude and scale of devastation as vast as this, and that the proportionality of war-wounded children was higher than any other war I’d worked in.

One day, four of the five patients we were resuscitating from the brink of death were under the age of fifteen. I told them of the Palestinian doctors—forcibly displaced multiple times and forced to scavenge for shelter, food, and water for their families—who would still show up to work. How, stethoscope in hand, they pronounced their own family members dead, took a moment to weep, and then returned to treating patients.

I recounted how I could feel Israeli forces closing in on the hospital—the whooshing sounds of airstrikes pounding louder, closer. One day, a bullet whizzed through the ICU. The next day, the road to the hospital was deemed unsafe for us to use. The Israeli military then dropped leaflets designating areas surrounding the hospital as a “red zone.” Given the history of attacks on medical staff and facilities in Gaza, our team was unable to return. Patients evacuated in panic.

I told them how this targeting of hospitals should offend every sense of civility in us all. I don’t know if my patients got out. What of the orphan missing a leg? How do the siblings with facial burns and eyes swollen shut see well enough to evacuate? What happened to my babies in the neonatal ICU incubators?

In war, I said, we talk of the fall of cities. The Fall of Mosul. The Fall of Saigon. I asked when it became normalized to speak of the Fall of Hospitals. The Fall of Al-Shifa. The Fall of Al-Aqsa Hospital. Voyeuristic onlookers to grief, we watch the landslide, somehow accepting that these are the new rules of engagement, all the while pretending to be a rules-based society. This grotesque disregard for life has birthed a generation of amputated orphans. Finally, I made sure they knew that the fate of these children lies in their hands now.

One of Dr. Jilani’s patients in a Gaza ER suffering from traumatic amputation of his right arm and right leg due to Israeli bombardment. December 2023.

One of Dr. Jilani’s patients in a Gaza ER suffering from traumatic amputation of his right arm and right leg due to Israeli bombardment. December 2023.

Afterwards, I called my father, a boat refugee from Partition, and told him I had delivered on his fantasy, fulfilling his American dream of earning a seat at the table. What I did not tell him was that I went into that room seeking their validation and, when I left, I did not need it anymore.

I was apprehensive about meeting Miliband, but he surprised me. Myself and three British physicians, including two with Oxford accents, briefed him in an online meeting. Sharply dressed, with a library of books behind him, Miliband was curious and full of praise for our team. The assumption about him needing an Oxford accent to take me seriously was clearly false. He listened in earnest, dutifully taking notes.

Afterwards, I wondered if he, the IRC, or any of the other institutions that I had spoken to would do anything with my recommendations. But that would be their burden to carry, not mine, and their hypocrisy to wash away. I was not the imposter.

I have since left the IRC. While still continuing to work in war zones, I have also resumed my clinical medical work in Texas, another kind of frontline, where different freedoms are under assault, whether through draconian abortion laws or undocumented immigrant health care at risk. I make life or death decisions for these children. I can order blood transfusions for kids with cancer, call a code blue to get them to the Intensive Care Unit, or even pronounce them dead. But I still cannot speak out on Gaza and have it result in meaningful change.

Now I can focus on dismantling the systems of subjugation, the very systems we believed would free us.

Fatima cauterized things with surgical precision when she told me, “The soft power of the West was very alluring. The sense that it was a place of freedom, had this scope for voices like ours, that someone cared about diversity—those ideas were seductive. Gaza has shattered the myth of these institutions I respected. I don’t think it will ever be possible to see them in that light again.”

“I’m not defeated by it because it really frees us from imagining that these are the only places that matter,” Fatima continued. “Our worldview just expanded enormously if we can let that go now. New things are already being built. People are investing their time and grief and heartbreak to change spaces.”

Gaza has lifted the thin veil of polite discourse. My realization came late, but this is only a repetition of the shattered illusions of so many people from the Global South who have put their trust in Western values. It has left me feeling unburdened, allowing me to bury the ghost of the grateful, model minority, never to be resurrected.

While still vital to speak up in the rooms where powerful people make decisions, I know the role of people like Fatima, Najla, and myself is much broader, and the burden far heftier; getting access to the room is no longer the goal, begging to be seen as equals is beneath us. Every child of a refugee knows that we must be smarter, fiercer, grittier than our counterparts; we do not have the luxury of making mistakes. I am now fortunate to be disabused of the notion that achieving success on the Western barometer could ever guarantee that I have any true influence.

Now I can focus on dismantling the systems of subjugation, the very systems we believed would free us. Now we can stop swallowing the indignities of erasure just to worship at the altar of respectability politics. The saving grace as a people for whom imperialism is sewn into our very DNA is that we have an arsenal of ancestral fury to draw upon, with which to build anew.

Though Fatima and I commiserate over the sting of this betrayal, she is heartened. “The West has lost its authority over us,” she told me. As we spoke, the next generation of our diaspora—her infant son and my young daughter—summoned each of us. Just before leaving to refocus our attention on them, she told me, “It has no moral authority, no political authority, no spiritual authority. It has nothing for us to aspire to anymore. It has been very liberating.”

Seema Jilani

Seema Jilani is a pediatric specialist who has worked in Afghanistan, Gaza, the West Bank, Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, Egypt, Bosnia, and on refugee rescue boats off the coast of Libya. Her radio documentary, Israel and Palestine: The Human Cost of the Occupation, was nominated for the Peabody award.