A Vanishing World: On Europe’s Disappearing Peasantry

Patrick Joyce Explores the Social and Cultural Transformation of Rural Life

You travel north from my father’s house on the Galway-Mayo border in Ireland’s far West. North and west of you and never far away lies the Atlantic Ocean. Belderrig is reached after a long drive, for the county of Mayo is big, and the narrow country roads take long to travel. Though not as long as in the days of J.M. Synge, that great theatrical fabulist of peasants, who over a century ago took the same roads as me as he went north into Mayo in search of rural Ireland.

Along the way the land is thinly populated, less than 10 percent of the population density of England, less than a third that of Ireland as a whole. Once, before the Great Famine of the 1840s, the county teemed with people, so many that the famine could not take them all. Despite its catastrophic failure in the 1840s, the potato crop kept them alive after that time just as it had done so before.

In Mayo the ridges on which the potato was grown centuries ago are still visible in the landscape, still there, but now grown over. There is an old Irish proverb about potato ridges: three times the life of a whale is the lifespan of a ridge, and three times the life of a ridge is the lifespan of the world.

Belderrig (Béal Deirg) is a tiny and remote settlement at Mayo’s northern Atlantic margin. It lies 4 miles to the west of Céide Fields, a prehistoric landscape of field systems and domestic and ritual structures created by Neolithic farmers and said to date back 5,700 years. Céide Fields is recognized by UNESCO as the most extensive Stone Age monument in the world and the oldest enclosed landscape in Europe. The low straight piles of stones are an indication of land cleared for pastures, and perhaps for crops too.

Certainly, later on, there are clear indications of the arable “Celtic field” type common in north-western Europe and lasting from the later Bronze Age (two and a half millennia ago) for almost 2,000 years. The blanket bog under which the 5 square miles of the Céide Fields lie is up to 16 feet deep in places, as it slopes down in a great horizontal arc to the North Atlantic below.

The ending that was the vanished world of the isolated hill bachelors is only one vanishing in this place of many vanishings.

In 1974, Seamus Heaney composed a poem called “Belderg.” Here are two stanzas from it:

A landscape fossilized,

Its stone-wall patternings

Repeated before our eyes

In the stone walls of Mayo.

Before I turned to go

He talked about persistence,

A congruence of lives,

How, stubbed and cleared of stones,

His home accrued growth rings

Of iron, flint and bronze.

Iron, flint and bronze: the ages of human culture, going back 3,000 years and more before Christ, the rings accruing around a home that is, however now, in the present. The words speak of recurrence, of persistence and of a congruence of lives over great stretches of historical time, the ghosts of the past not deserting us. The potato ridges speak about a time that is shorter, but it is the same things that are spoken of. For the potato is still sown here around Céide Fields just as stone walls are still built.

The site was discovered in the 1930s by the local schoolmaster Patrick Caulfield when out cutting his own turf (turf is peat, cut then in Ireland by all for fuel, but these days by fewer and fewer). His son Seamus, an archaeologist, went on to excavate the site and so to end this long vanishing, even though the bog remains relentless in its annual growth, fed as it is by the immense wetness of the place. The houses are built to withstand the Atlantic winds, which are as constant as the Atlantic rains.

It is Seamus the son who talks in the poem, it is his home that is mentioned. And it is Seamus the poet who listens, the poet who was the son of a small farmer like those around here, a man who had a deep affinity with this agricultural landscape. Heaney’s father farmed further north, although Mayo’s north is well on the way to Heaney’s, and Belderrig’s churchyard is full of the “Macs” who proliferate in the North.

My father came from the same kind of people as live and lived here and, 50 miles to the south, in Galway’s north, in Rosshill graveyard beside the village of Clonbur, lie many Joyces. For this part of Ireland has of old been called the Joyce Country, Dúiche Seoighe in Irish. Dúiche is derived from Dúchas, which is a term akin to “patrimony” in French. It is an Irish language noun that fuses the sense of the innate quality of a person or a way of life with the idea of these being located in a particular place. The idea of an inheritance handed down is also present, one that makes one truly a native of a place. The word conveys much more than “country” in its English translation (“duchy” is also there, in the English word), more than the sense of “home” also, which it nonetheless embraces.

Dúiche Seoighe is essentially the northern part of Connemara, and so, like Belderrig, Irish-speaking. The last remnant of the little that is left of the old Gaelic culture. The Joyces lie with ample numbers of Coynes, Flynns, Lydons and others, the family name in Ireland still a great marker of place. The Bowes of my mother’s side of the family lie with the Kents, Corishes, Englishes and Sherlocks in a different Ireland, that of Wexford in the island’s south-east corner. But, in one sense, that Ireland is pretty much the same as Joyce Country—it too is the land of the small farmer, though there the farms are bigger if not greatly prosperous, at least around the 50-acre mark of my mother’s place, the “home place” as the house and farm are called in Ireland.

Unlike Heaney’s parents, mine were forced to leave Ireland in the 1930s. My father first went to England in 1929, then back and forth for a while working, as they all did, on “the buildings” (construction). Then finally he settled in London, marrying my mother, Kitty Bowe, in 1944. Three years younger than my father, she first went to England in 1932. Kitty was the daughter of a farmer better off than some around him, though what advantage the family had in terms of good land, and more of it than in the West, was whittled away by the ten mouths that had to be fed (those being the mouths that survived, four children dying very young), and by a father, a spoiled only child by all accounts, who is said to have drunk away the equivalent of three farms of land.

Four out of five of my father’s siblings emigrated, three to the USA, for long the favored destination of the western parts of Ireland. On the somewhat more benign, eastern side of my mother’s Wexford, three out of the ten who survived left for England, and most of the girls who did not go to England were spread around Ireland and far from home. Born to leave, as they say, at least then, emigration having been the pattern for centuries, especially in the post-famine West.

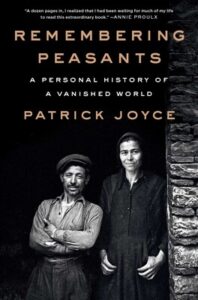

This is the face of one of those who stayed, a face I loved. The photograph above is of my cousin Seán Joyce (1941–2002), Seán Seoighe, a small farmer-cum-peasant. A man of whom it was always said that he was of the old school, even by the old schoolers themselves. He was the youngest child, and the only son, and thus the one who inherited. A “peasant proprietor,” in fact, a figure that in the Ireland of his childhood and youth was the ideal of the newly independent state, a nation only nineteen years old when he was born. This state, made in the image of the imagined peasant, was conservative and clerical. It is an image many of the Irish now prefer to forget. This forgetting, understandable in part, is in larger part a loss of the greatest magnitude.

There is a certain distance to Seán’s outward gaze: the photograph was taken by a holidaying American “stranger” (with no Irish connections but those in the head). It seems to me the sitter would have found it awkward to present himself to the camera, unlike the posing of the holiday “snap,” for which he would have tidied himself up (the Sweet Afton cigarettes bulge from the pocket of his none-too-tidy shirt). His hands, just visible here, tell of the peasant, for they are big, made big by toil.

Seán was a big man, 6 feet and 5 inches. At work early, as the children were then, he left school early too, a farmer at thirteen years old, his father Stephen dead before his time, just like Stephen’s brother, my father Johnny. Seán sits in the kitchen of my father’s house, the house he had to leave, the new house of 1905, nearer the road (but still a long way up Kilbride Mountain) than the old one before it. The mountains took Seán’s life, for he worked all hours, in all weathers, until his legs gave way and he could walk no longer. He lived his life alone, a bachelor, well cared for by his kin, who managed his obduracy as best they could. Seán was a hill bachelor, as such men are called in William Trevor’s literary account. The ending that was the vanished world of the isolated hill bachelors is only one vanishing in this place of many vanishings, vanishings past and present, those of famine and massive migration.

The Joyce Country is a small block of land to the east of which are two wide lakes, Corrib, and Mask, to Corrib’s north. On the other, western, side lies the Atlantic Ocean. Hemmed in and separated by water as it is, it is a remote and difficult region to access. The area straddles the county of Galway in the south and Mayo in the north. Immediately to the south of it once lay the single biggest landed estate in Ireland, the almost 200,000 acres known at the time of the famine as the Martin Estate. The late Tim Robinson was a renowned chronicler of Connemara and its vanishings. In 1995, Robinson edited the journal of a survey of the Martin Estate made in 1853, the aim of the survey having been to present to potential buyers an investment opportunity of unrivaled possibility, now that the estate was free of the encumbrance of living souls. This is a passage from the journal:

The very dogs which had lost their masters or were driven from their homes became roving denizens of this district and lived on the unburied or partially buried corpses of their late owners & others, and there was no help for it, as all were prostrate alike, the territory so extensive, and the people so secluded and unknown.

This next image is a different sort of photograph. An “art” photograph, one might say. It is titled “Irlande 1972.” It is from a collection of the great Czech photographer Josef Koudelka entitled Exiles. The three men kneel at the summit of Croagh Patrick in the far West of Ireland, the Atlantic Ocean immediately below. Croagh Patrick has been a site of pilgrimage for over a millennium and a half. In the background is Clew Bay, and the town of Westport lies only a few miles east of here. There is no mistaking Koudelka’s employment of the imagery of the Crucifixion in the photograph.

The man on the right of the image is my cousin Seán Joyce, then only twenty-eight years old. Again, as in the first image, he looks out at the camera and the man who holds it with some suspicion. On the left of the central figure is Paddy Kenny (Pádraig Ó Cionnaith), who was married to Seán’s sister Sally. In the middle is a close friend and neighbor, Martin Mangan (Máirtín Maingín). Again, the size of their hands is apparent, the sign of those who work the land. They lean on blackthorn sticks, which they will have fashioned with these hands. I do not know for sure if that year they had walked the twenty and more miles over the hills from the Joyce Country, but they did this often, as was the custom (there were precious few cars around locally in 1972 anyway). Many did and still do make part of the ascent of Croagh Patrick on their knees.

My kin have somehow become epic, monumental…. They have become as monuments to the vanishing of peasant Europe.

The men seem separated from the others around them, not only by distance but by the gravity of their demeanor; the other figures seem to be admiring the view, the three men are aware of this holy place, where St. Patrick is held to have appeared. The dark hair of the three men is striking, like so many from the West. They wear suits, to us perhaps a strange garb for such a journey as theirs, but this is a sign of their respect, of gravity realized. My kin have somehow become epic, monumental. Such is the power of the photograph. They have become as monuments to the vanishing of peasant Europe.

My eyes look up from these photographs of Seán Seoighe, and I see that the span of his lifetime is essentially the same as that of the end of peasant Europe.

The urban-dwelling proportion of the world’s population has increased from just over 20 per cent of the total in 1950 to approaching 60 per cent today. Most of these people live in the cities of the Global South, once the locations of little but the vast peasant millions. The pace quickens: between 1991 and 2019 the proportion of the world’s population engaged in agriculture fell from 44 per cent to 27 per cent. And yet not so long ago the world looked very different.

Within my own span of years, as an adolescent I saw the Spanish peasantry laboring in the fields in the poverty-disfigured Spain of the early 1960s, riding for days and nights the fourth-class wooden railway carriages of the time, the people of the land I passed through constantly getting on and off the train, something easy to do, given the slowness of the passage through the great open spaces of Castile and Andalucía. And I remember the delight and kindness shown us by these peasant fellow travelers as they came and went in the darkness of the night, ever ready as they were to share their food with us, and pass their goatskin-covered wine casks to those reciprocally delighted working-class Irish London boys, visitors from another world now united in the comradeship of the fourth-class carriage.

Between 1950 and 1970 the Spanish peasantry almost halved in number. Yet this still seemed to be a world that had changed little over centuries and would continue to survive into the future. We did not know then that it would end so abruptly. In Spain agricultural workers formed just under half the population in 1950. This was reduced to 14.5 per cent by 1980 (to 17.6 per cent from a similar earlier number in Portugal), and to less than 5 per cent of the workforce by 2020.

The Andalucíans had gone to neighboring Catalonia, Barcelona especially, and spread out across Europe; the Portuguese to France and beyond. In the Ireland of the 1950s perhaps as much as a fifth of the population left for the British cities. This was the story everywhere in Europe, even in the Communist East, where the decay of the peasantry was not so marked. Italy, too, was transformed very early after the war by the vast movement of people from the rural South, the Mezzogiorno, to the rapidly industrializing North.

Not only was Seán Seoighe’s span of life led concurrent with the vanishing of peasant Europe. The bachelor life he led was itself a sort of emblem of what happened far beyond Irish shores. Pierre Bourdieu, born in 1930, was the son of a village postmaster in the ancient province of Béarn in France’s extreme south-west. Béarn neighbors the Basque regions and the Pyrenees, and the land is pastoral and upland, like the West of Ireland. It is, or rather was, an area with long-established traditions of peasant landownership, traditions much older than Irish ones. Bourdieu is generally regarded as one of the major intellectual figures of his time, a great sociologist. In a book called The Bachelors’ Ball, he collected his work from the early 1960s to the 1980s on his native region.

Bourdieu had a deep care for the people of the world he was born into. He writes that he wanted to protect his people from ill-intentioned or voyeuristic readings. He is full of anger at what peasant France had become in his lifetime, a treasury of relics to be consigned to the theme park. In France, as in Ireland. Almost despite himself, Bourdieu confesses his “pent-up tenderness” in the description he gives of what is the symbolic center of his story, his account of the “ball.”

It’s a small-town dance night, in which the peasant bachelors assemble in the hope of finding wives, an unavailing hope, for who wanted a clumsy peasant from the back of nowhere in the modern days of the 1960s and ’70s? The peasant ball, the country dance, becomes in his hands the great symbol of the death of the peasant world. Failure to marry removes the central axis of peasant culture, he says. Failure to marry because the young women had almost all gone, drawn by employment opportunities open to women in the cities.

These peasants were raised in a culture where male and female society was much more strictly demarcated than in ours, and where to us now relations between the sexes seem to have lacked naturalness and freedom. Church, school and rural custom were the policemen of the division. In the towns and the villages of Béarn, a more liberal culture was taking hold, making the peasant’s body a burden to him and a deterrent in the marriage market. In the ballrooms of rural and small-town Ireland similar things were being enacted at the same time. These ballrooms of romance have been described by William Trevor as places where the bachelor felt the heavy weight of his own body.

In his account of the ball, Bourdieu catches the gaucheness and discomfort of the peasant body and demeanor when confronting a culture that is not his own, meeting people not like him, but still part of his local world, one from which he hopes to find a bride. The author captures the mixture of pride and shame the peasant feels at the ball, or, if not always shame, then an acute awareness of his shortcomings.

Contempt and homage are mingled together before the people of the town, the ball a reflection of everyday life. In his ordinary dealings the peasant is clumsy and embarrassed facing the townspeople. Peasants’ bodies are like that of Seán Joyce, possessed by the labors they must perform. In these French upland areas, these bodies bear heavy loads across uneven and sloping ground, so that they are slow and ponderous in movement, not to the men themselves, but to outsiders.

Bourdieu tells of how the peasant internalizes the devalued image that others form of him through the prism of urban categories, and comes to perceive his own body as an “en-peasanted” one, burdened with the traces of agricultural life. He sees his body through the eyes of the beholders at the ball. The consciousness that he gains of his body leads him to break solidarity with it and to adopt an introverted attitude that amplifies his shyness and gaucheness. In a phrase that is truly terrible the author writes of this as a social mutilation, bachelorhood inducing in many cases an attitude of resignation and renunciation resulting from the absence of a long-term future. Peasants use the same words of insult upon their own kind as are directed to them: cul-terreux, plouc, péouse and others. Earth, territory, heavy clods and heavy gait, the peasant even speaks with an accent du terroir.

In Béarn as elsewhere in peasant Europe, the house—”la maysou” in the Béarnese dialect—and the family name were the same, the lineage and patrimony of the family house (“la maison”) together. The name and the house live on together even when the family that personifies and perpetuates them has gone. The house carries the name, even if uninhabited. But with time the uninhabited house falls into decay and the name is gone, the bachelors’ ball now long a thing of the past.

__________________________________

From Remembering Peasants: A Personal History of a Vanished World by Patrick Joyce. Copyright © 2024. Available from Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Patrick Joyce

Patrick Joyce is Emeritus Professor of History, University of Manchester. He is a leading British social historian and has written and edited numerous books of social and political history, including The Rule of Freedom, Visions of the People, and The State of Freedom. Joyce is also the author of the memoir Going to My Father’s House, a meditation on the complex questions of immigration, home, and nation. The son of Irish immigrants, he was raised in London and resides beside the Peak District in England.