A Stone You Never Put Down: The Secret Languages of Grief

Carol Smith on Finding a Lexicon Beyond Words After Unimaginable Loss

In the country of grief, none of us speaks the same language.

We have all kinds of ceremonies that come with long-standing traditions to help the bereaved through the initial shock of loss. Funeral processions and memorial services, wakes and shivas, second-line parades—each of these has its own language and customs. But what follows those public outpourings is a long, private stage of mourning. And for that, each of us develops our own secret language.

After my son Christopher died unexpectedly at age seven, words failed me. There is no dictionary for grieving. No word for the crushing weight of absence, no word for the instant of disbelief in the morning just after you wake, or for the fatigue beyond exhaustion that hollows out the bones. In Macbeth, Shakespeare writes, “Give sorrow words; the grief that does not speak knits up the o-er wrought heart and bids it break,” My grief was unspeakable. I lacked the vocabulary.

When well-meaning people asked how I was doing, I lied. “Fine,” I’d say. It was too hard to explain otherwise. Still, I craved some way to convey what I felt. I began searching deep into the roots of words for clues.

The word grief, for example, comes from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root gwere for heavy. Gwere – to even say it (as we would pronounce it today) is to exhale sharply as though trying to catch a heavy, falling stone against the stomach, which is indeed what it is like to discover a loved one has died. Gwere evolved into old French grever, the more immediate ancestor of our term for grief. Grever, meaning burden. Yes, that is what it is like. A stone you never put down.

According to online etymology sources, the word sorrow may derive from the word swergh, the PIE root for sickness. That, too, made sense to me. The physical symptoms that stem from mental anguish—nausea and weakness, confusion, the stuttering heart rhythms that leave you faint, the ruthless insomnia—this was what sorrow felt like, my body trying with every cell to reject this new and certain reality.

Loss, in turn, descends from the ancient root leu, meaning “to cut apart.” Mourners in some Native American cultures cut their hair off as a sign of their grief. It used to be customary in New Guinea for some members of the Dani Tribe to cut off the tip of a finger upon the loss of a family member or child. I understood this impulse. Losing my child felt like an amputation.

Yes, that is what grief is like. A stone you never put down.Years later, I would hear the poet Richard Hoffman, author of Half the House and no stranger to grief, say that the word “overwhelm” derives from over-helm, as in the helm of a boat—the feeling of being cast overboard. That, too, approached my feeling during the early days after my son’s death. The sense of drowning.

I thought if only I could explain, maybe someone, in turn, could give me language to staunch my pain. But there were equally no words that comforted me.

Well-worn euphemisms and platitudes—“sleeping with angels” or “he’s in a better place,” or “God doesn’t give you more than you can handle”—had the unintended effect of enraging me. Shortly after Christopher’s death, I opened a letter sent by a woman I didn’t know well, a friend of a friend who had never known Christopher. She wrote how she was sure Christopher was playing with her grandmother in heaven, how she could picture him sitting on her grandmother’s lap. She intended it to be a comfort, I’m sure, but the letter left me seething, as though she had stolen my child for her selfish fantasy. I stalked around the house, rehearsing hurtful, sarcastic replies to her and all the others who tried to comfort me with clumsy words that wounded instead, who said at least he went fast, who said I should be happy to have had him as long as I had, who said I was strong enough to handle this.

I wasn’t strong.

I grasped at metaphors to try to make sense of what was happening. Grief is a hard wall that imprisons, a high wall that shuts out the light. My journals from the early days after Christopher died are filled with these fragments. Grief is consuming, like fire. A riptide that drags you out to sea. A vortex that tears you apart.

Many years later, my cousin was killed in a gliding accident. I struggled with what to write my aunt and uncle, thought of all the words of comfort that hadn’t comforted me after Christopher died. I sat down and wrote:

Grief is like a sharp rock embedded somewhere inside you. At first it cuts no matter which way you turn. But over time, the edges of it soften—like a rock tumbled in a river…

My aunt Mary Lou never opened my letter, or any of the others that arrived. Nor did she open the ones that came after my uncle died a few years later. She did not want to read condolences. She went behind the wall.

Eventually, I found my own kind of consolation in a language deeper than words—a private lexicon of symbols.

After Christopher died, I wanted a touchstone to remember him by. I settled on a little compass star I wear around my neck. It reminds me of how we loved to watch the night sky together, counting stars and searching for familiar constellations—the Big Dipper and Orion’s Belt. When I touch it, I can almost smell his little boy scent of crayons and green apples. Almost feel his breath against my throat when he’d snuggle against me while we read a book. When I think of him, I touch the star, and now it acts as a kind of synecdoche—a talisman that conjures all kinds of different memories. It protects me from the finality of his absence, the fear that I will somehow, someday forget the sound of his laugh or the weight of his sleepy body when I carried him to bed.

The custom of wearing talismans and amulets for remembrance and protection has been with us for centuries. During the pre-Georgian era, people wore jewelry worked with images of skulls and grave-diggers’ tools. These pieces often bore the motto: Memento Mori. Remember death. They let the wearer consider their own mortality on a daily basis, perhaps as a way of inoculating themselves against the inevitability of loss. Or softening the shock of it when it struck their inner circles.

In the eras that followed, the practice of wearing jewelry to signify grief moved away from images of death. Queen Victoria lost her husband Albert when she was forty-two and grieved him the rest of her life, giving rise to a cultural passion for mourning dress and jewelry. Like a “widow’s weeds,” mourning jewelry was often dark, made of jet or black enamel. Instead of memento mori, the inscriptions became “In Memory Of.” Instead of skulls and bones, they bore portraits of the bygone.

After my great-aunt Mabel died, my mother inherited a small box of her jewelry. We used to go through the box together, fingering each delicate piece and wondering about its story. There was a gold locket with a weeping willow and an urn enameled on the front as well as an oval brooch encircled with seed pearls said to symbolize tears. We puzzled over a small gold heart, no bigger than a thimble, cross-hatched with woven hair like a tiny basket. Or the long delicate braid of hair fashioned into a chain. These mementos seem a little macabre by modern standards, and yet, I sometimes wear another locket of hers that contains a picture of her brother – my grandfather – and remember how he used to pretend to pull a quarter from behind my ear on hot Houston nights, then send me and my brothers outside for lime popsicles from the ice cream truck.

Decades later, our tastes in mourning symbols have shifted yet again. Rather than wearing literal reminders of our loved ones—their portraits or their hair—we more often choose a code of our own making, something that has meaning only to us—a star, in my case. For someone else, it might be a hummingbird or a rose, a fairy or a phrase their loved one used to say. These words and images get stamped in silver or gold or tattooed somewhere on the body. There are as many ways to grieve as there are people to mourn.

Though no one would know but me, a walk through my house is a gallery of my losses, but also of what remains, the imprint of love these people left on me, a palimpsest.Over time, a whole personal vocabulary of grief emerges, too, one that reflects the many losses that accrue to us as we grow older. Sometimes it’s not even a conscious vocabulary. I keep a bowl of fresh lemons in my kitchen and many years later, I realized it’s because they remind me of my grandmother’s lemon cake. I keep a little globe that belonged to my uncle tucked next to my travel guides and touch it for good luck when I leave on a trip. I plant paperwhites to bloom for the holidays because I have a favorite memory of Christopher picking me a blossom from a bowl I’d just gotten to bloom.

When Christopher was little, he dropped a fragile purple sea urchin shell I’d given him to look at. It smashed into pieces on the tile bathroom floor. As I swept the pieces into a dustpan, he cried as though his heart had shattered. He insisted on keeping a small purple shard. What is broken can’t be made whole, but we carry the fragments with us anyway. I keep a similar shell on a shelf next to my bed to remind me that it’s my heart that shattered.

Though no one would know but me, a walk through my house is a gallery of my losses, but also of what remains, the imprint of love these people left on me, a palimpsest. These secret gestures bring me comfort.

These symbols are how I give my sorrow words.

_______________________________________________

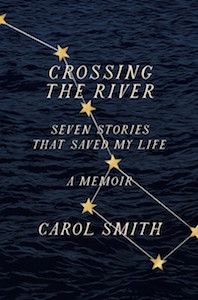

Carol Smith’s Crossing the River: Seven Stories That Saved My Life is available now via Abrams Press.