“A Source of Amyuzmint.” On the Use of Bad Spelling in Early American Comedy

Gabe Henry Considers the Creative Intentions and Class-Based Undertones Behind Phonetic Writing

“I attrybute my suksess in life to mi devoshun to spelyng.”

–Josh Billings

*Article continues after advertisement

Simplified spelling looks silly. There’s no getting around that. For most readers today, the mere sight of words like “nolej” or “edukayshun”—or any of the countless others pushed by the “simplified spelling movement” in its centuries-long quest to phoneticize English—instantly sets the funny bone a-tingling, and no matter how logical the argument for spelling reform, they’ll never see it as anything but a source of amyuzmint. In that sense, not much has changed since the 1800s.

As the simplified spelling movement gained ground in the nineteenth century, America’s humorists couldn’t resist poking fun at the pedantic craze. Wits like Artemus Ward (“Toosday nite I peared be4 a C of upturned faces in the Red Skool House”) and Petroleum Vesuvius Nasby (“I hev bin in the Apossel biznis more extensively than any man sence the time uv Paul”) capitalized on the growing appeal of simplified spelling by turning it into an irreverent form of wordplay (letterplay?) and eventually into its own micro literary genre.

In 1864, when Josh Billings failed to find an audience for his “Essay on the Mule,” he rewrote it as “Essa on the Muel” and it launched his literary career. Suddenly, Billings was the comedic superstar of misspelled literature. “I attrybute my suksess in life to mi devoshun to spelyng,” he once wrote, and he wasn’t kidding: spelyng, or rather “misspelyng,” became his brand.

While dialect writing serves to bring depth or authenticity to a character, simplified spelling humor aimed merely to entertain.

He found his calling in 1870 with his “Farmer’s Allminax,” an annual parody publication that offered phonetic advice to young men (“Dont be diskouraged if yure mustash dont gro”) and monthly “horoskopes” (“The yung female born during this month will show grate judgement in sorting her lovers, and will finally marry a real estate agent”).

Billings, Nasby, and Ward were known collectively as the “Phunny Phellows”—humorists who cashed in on the inherent silliness of simplified spelling. In the 1880s, critics began grouping another author with them: Mark Twain. Twain had been toying with quasi-phonetic spelling for years, but it was his 1884 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn that earned his induction into this merry band of misspellers. “The Widow Douglas, she took me for her son,” says the ruffian Huck Finn, “and allowed she would sivilize me.” For Billings and his ilk, simplified spelling was not only an easy laugh but a mark of socioeconomic class.

With their laffably low-class, comically uncouth spellings, the Phellows turned phonetic orthography into a marker of indignity.

Simply by simplifying the spelling of a character’s speech, they could indicate their humble background. The simpler they spelled, the less sivilized they were. Simplified spelling humor is a close cousin of “dialect writing,” a literary device that uses distorted spelling in the vernacular of a (usually low-class) character. Eliza Doolittle might be the eternal archetype: “Ow, eez ye-ooa san, is e?” she warbles in her signature cockney, dutifully transcribed by her author George Bernard Shaw.

“Wal, fewd dan y’ de-ooty bawmz a mather should, eed now bettern to spawl a pore gel’s flahrzn than ran awy atbaht pyin. Will ye-oopy me f ’them?”

The techniques of the simplified spellers are there, if subtle: flowers rewritten as flahrz, girl rendered as gel. But while dialect writing serves to bring depth or authenticity to a character, simplified spelling humor aimed merely to entertain. It was primarily a visual gag, not an expression of dialect. It was more for the eye than for the ear. Jokey misspellings had been on the rise since the 1830s, when a brief orthographic fad captured New England’s journalists. Certain writers would amuse themselves with an inside joke: First, they would deliberately misspell a short phrase. “No go,” for instance, would be “know go.” Then they would abbreviate that misspelling, as though communicating with each other in insider shorthand. “Know go” thus becomes KG. “No use,” respelled as “know yuse,” was abbreviated as KY. OW meant “all right” (“oll wright”) and OR meant “all wrong” (“oll rong”). NC was “enough said” (“nuff ced”). And OK—the Lone vestige of this lingo—meant “all correct”— that is, “oll korrect.” “OK” debuted in a Boston newspaper on March 23, 1839 (“OK Day,” to those who observe) and quickly caught on. A year later, the Boston Daily Times printed a poem on the trendy sensation sweeping New England:

What is’t that ails the people, Joe?

They’re in a kurious way,

For every where I chance to go,

“Affurisms” by Josh Billings (a selection)

“Laffing iz the sensashun ov pheeling good all over, and showing it principally in one spot.”

“There iz only one good substitute for the endearments ov a sister, and that iz the endearments ov sum other pheller’s sister.”

“A good reliable sett ov bowels, iz wurth more tu a man, than enny quantity ov brains.”

“There iz 2 things in this life for which we are never fully prepared, and that iz twins.”

“Suckcess iz az hard tew define az falling oph from a log, a man kant alwuss tell exackly how he did it.”

“Flattery iz like Colone water, tew be smelt ov, not swallowed.”

“Most ov the happiness in this world konsists in possessing what others kant git.”

“I don’t know ov a better kure for sorrow than tew pity sum boddy else.”

“He who wears tite boots will hav too acknowledge the corn.”

There’s nothing but o.k.

They do not use the alphabet,

What e’er they wish to say,

And all the letters they forget,

Except the o. and k.

I’ve seen them on the Atlas’s page,

And also in the Post,

When both were boiling o’er with rage,

To see which fibbed the most.

The Major has kome off the best;

The Kurnel is surprised!

The one it seems meant Oll Korrect,

The other, Oll kapsized!

Processions have been all the go,

And illuminations tall;

Hand bills were headed with k. o.,

Which means, they say, kome oll!

The way the people sallied out,

Was a kaution to the lazy;

And when o. k. I heard them shout,

I thought it meant oll krazy.

…This theme has on Pegasus’ way

Most wantonly obtruded,

And now, with joy, I have to say

It’s o. k. oll konkluded.

Yet four more lines I needs must write,

From which there’s no retreat,

O. k. again I must endite,

And—lo!

It’s oll komplete!

Newspapers played a pivotal role in relaxing the spelling norms of nineteenth-century America. Confronted with the dual demands of capturing reader attention and navigating narrow column space, editors began adopting abbreviated, catchy headlines. Words were shortened, and alternative spellings like thru and nite became common practice. The Phunny Phellows were all former newspapermen themselves, and they used the tricks of their journalistic trade in their comical storytelling. Eventually, the Phunny Phellows found they could make more money taking their humor writings on the road and “performing” them for audiences.Their rough-speaking, semiliterate, jargon-heavy characters made for great one-man comedy (even if the phonetic spellings didn’t translate to the stage), and humor-lovers around the country paid top dollar to watch the Phellows present their works in colorful vernacular. Dave Chappelle and George Carlin owe a great debt to the Phunny Phellows. They were the first comic monologists, the first literary funnymen to earn a living as live entertainers, and as a result are often considered the first stand-up comedians. Artemus Ward, the first of the Phellows, is hailed by many as the original king of comedy.

Phonetic antics of the Phunny Phellows would cast a long shadow over the simplified spelling movement. With their laffably low-class, comically uncouth spellings, the Phellows turned phonetic orthography into a marker of indignity, a style of writing closer to Huck Finn than to Ben Franklin. The Phunny Phellows would forever taint simplified spelling in the eyes of the world.

__________________________________

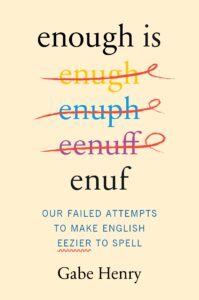

From Enough Is Enuf: Our Failed Attempts to Make English Easier to Spell by Gabe Henry. Copyright © 2025 by Gabe Henry. Reprinted by permission of Dey Street Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Gabe Henry

Gabe Henry is the author of Eating Salad Drunk: Haikus for the Burnout Age by Comedy Greats and the history-humor compendium What the Fact?! 365 Strange Days in History. Eating Salad Drunk was featured in The New Yorker in February 2022 (“A Smattering of Haiku for the Burnout Age”) and ranked one of Vulture’s Best Comedy Books of 2022. Henry’s work has been published in New York Magazine, The Weekly Humorist, The New Yorker, Light Poetry Magazine, and the Motion Picture Association’s magazine The Credits. In 2021 he co-created the trivia gameshow “JeoPARTY” (jeh-PAR-tee) with NPR’s Ophira Eisenberg. He lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.