“A Solid, Blue-Black World.” What William Beebe Found at the Bottom of the Ocean

Brad Fox on the History of Deep Sea Exploration

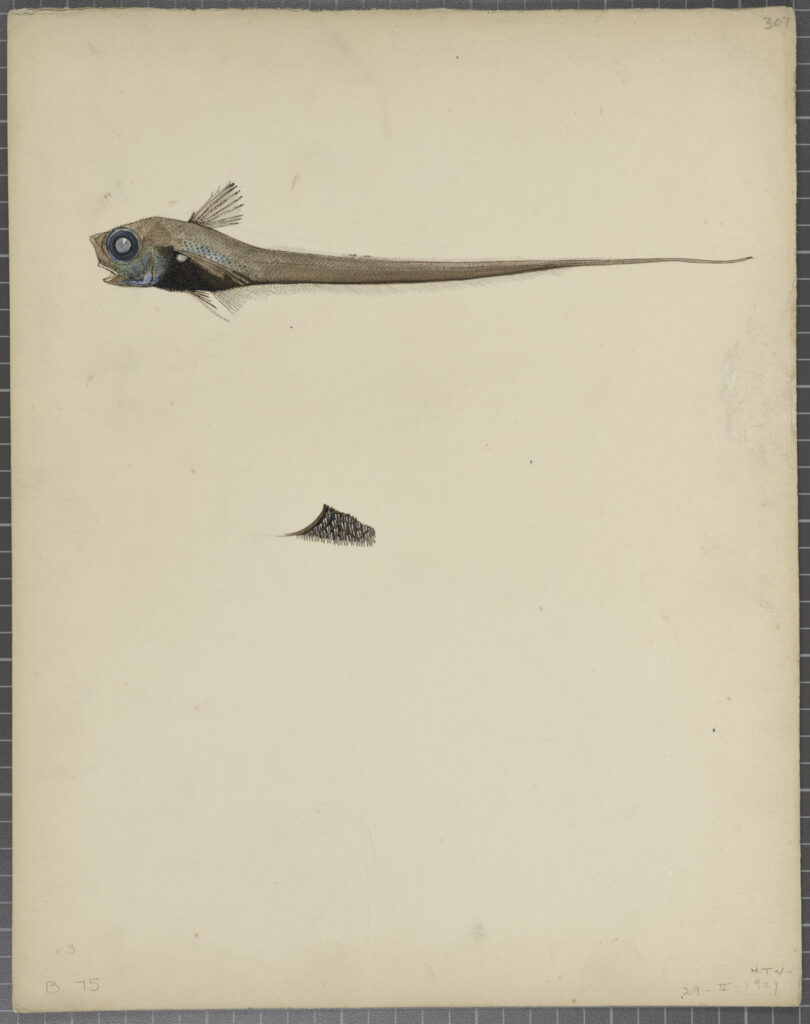

Linophryne arborifera

I saw a tremor run through the body—the fin waved two or three times, the tree-like growth of chin tentacles… a tangled snarl, then stretched wide to many times their contracted length, the mouth opened and partly closed, and the light went out of the great, staring eyes. What would I not have sacrificed to have been told what those eyes had seen in the black depths, what that great mouth had engulfed, what enemies had been avoided, what part might have the luminous head bulb played in courtship or in war, why the huge fangs should be luminous, why a great tree of hundreds of medusa-tentacles was necessary—why? why? Why?

Instead of which there lay my lifeless little dragon, perfect in all his parts, with his secrets hidden.

Beebe on a scrap of white paper, undated.

Animal Light

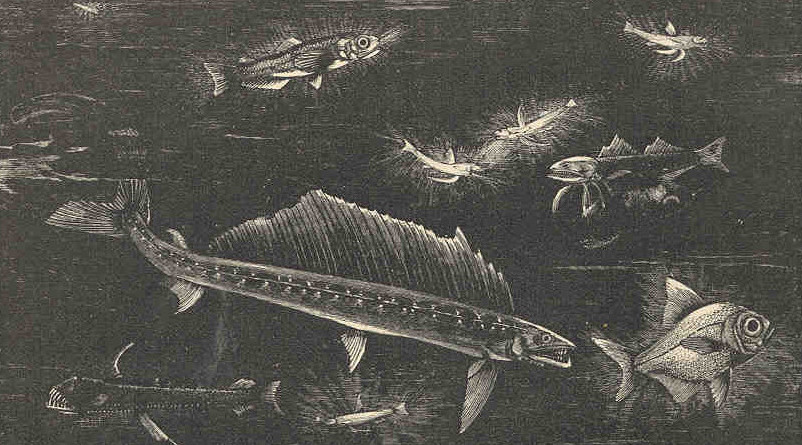

On a dark night twenty-five hundred years ago, a young Greek philosopher was out rowing off the city of Milet, near the mouth of the Meander, when he noticed swirls of light set into motion as his oars stroked the sea. Anaximenes, as he was called, was a student of the philosopher Anaximander, who had taught him that everything in the universe was made of the same indefinite substrata. Anaximander called it apeiron, but his own teacher Thales had taught him it was regular water that was the origin of things. Considering the swirls of light within the water, Anaximenes suspected it might be air that was condensed into water and eventually stones and animals and clouds and everything else. How else could there be light in the water?

The writers of the Sanskrit Vedas and early Chinese odes described the luminous bodies of insects and worms, but such creatures were rarely mentioned in the Mediterranean. Pliny wrote of strange glowing creatures called nyctegretos or nyctilops, but it wasn’t until the thirteenth century, when the Andalusian botanist Al-Bayṭār described an animal called alhubahib—a winged insect that lights up at night—that fireflies appeared in the history of the West. Al-Bayṭār recommended collecting their shining bodies, grinding them in rose oil, and dropping them into the ear to stop pussing wounds.

Books of medieval science soon filled with glowing animals. The forests of Bohemia were reportedly full of waxwings whose red-tipped feathers shone like the sun. Fiery vapors gathered around temples and especially cemeteries.

Cool light, like what shone from the mixture of sulfur and acid, was a matter of grave paradox.

Alchemists like Albertus Magnus and Paracelsus recommended burying the glowing abdomens of fireflies in manure and allowing the mixture to ferment. This produced what was called liquor lucidus, a glow-in-the-dark ink only visible at night or in pitch-black rooms.

The Swiss editor Conrad Gesner thought all glowing creatures were powered by the moon. He collected a thousand drawings of lunar animals before he died of the plague in 1555.

Twenty years later an English professor of divinities named Stephen Batman published an encyclopedic work on the natural world that contained an entry on the glowworm, a little beast that “shineth in darkness as a candle, and is foule and darke in full light.” Batman believed all these strange glowings were works of the devil and wrote about them in his book The Doome Warning All Men to Judgment.

Luminous fish appeared in the Margarita Philosophica of George Reisch. Glowing lamb’s flesh was reported in Padua. There were glowing eggs, glowing stones, and glowing clods of earth.

Francis Bacon saw light in the snap of a sugar cube, and Descartes believed cats could beam light from their eyes. The linens of honorable men, it was said, luminesced when removed in darkness.

Athanasius Kircher described sea creatures that could be rubbed on sticks so they glow like fire.

He had seen it himself in Marseilles and Sicily.

Thomas Bartholin claimed that humans, too, have been known to shine, especially when full of desire. His examples included Theodoric, King of the Goths; Carolus Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua; and an Athenian sex worker called Lampyris.

There were luminous minerals like the diamond, ruby, and carbuncle; there was the light emitted by dried cod. Light erupted when a woman combed her long hair in the dark. And all this was the result of fermentation. Sand on the beach was fermenting, cat’s fur was fermenting. The sun was a giant fermentation pot, a model to meteors and the air around the high mists of ships.

But unlike the sun, this light gave off no heat. Cool light, like what shone from the mixture of sulfur and acid, was a matter of grave paradox. Light was an exhalation of effluvium mixed with air, the attrition of gems; light was a corpuscular material body. There was cold fire confined in ætherial globules, calcined belemnites, in the boring mollusk brought to Bologna by Marsigli.

That light was a kind of matter was proved by the electroluminescence of evacuated vessels or mercury shaken in a glass tube. There were pyrophores and there was phlogiston; there was the phosphorus of Kunkel in the Torricellian void. Light shone from borate of soda, sulphate of argil, tartrite of potash, and silicious stones.

Bronislaus Rodziszewski found that compounds containing the triphenyl gloxaline ring give off light when dissolved in alcohol and shaken with air.

In 1799, Alexander Von Humboldt stimulated a jellyfish.

Darwin contemplated the bright thoraxes of Elateridae and the shining abdomens of Lampyridae. He thought animal light served to attract mates and food and confuse predators. MacCulloch thought it was to see in the darkness of the deep ocean.

Afloat on a small boat near Haiti a few years before, Beebe had noticed phosphorescence in the water and sent for a shotgun. He fired straight down, then marveled at what looked like a comet of glowing shot, arced into the deep and swept by a “train of trembling paleness.”

When he saw bioluminescent fish darting outside the bathysphere, they looked to him like “stars gone mad.”

The Blue Light of the Sea

The incandescence of animal light thrilled Beebe, and the chance to see exploding shrimp and glowing tentacles alive and undulating in their liquid home was one of the great thrills of the dives. But it was the luminous blue water, its ceaseless frequency like a maddening hum, that transfigured his being. He had read that below two hundred feet, blue was gradually replaced by violet. Below four hundred feet, violet was said to be dominant. But when he arrived at that depth, he didn’t see any violet. Instead, the blue deepened and became even more brilliant. He knew this was impossible, but he knew that’s what he saw.

Beebe was not looking through a chunk of glass but the entire ocean.

He read over an experiment where a scientist had shone ultraviolet light through a chunk of black glass. When light struck participants’ eyes, most saw a violet haze and were unable to see anything else. But others did not see the haze. Instead, they saw clear blue. It sounded like what happened to Beebe at depth.

Was it an aberration? An ability or disability?

Beebe was not looking through a chunk of glass but the entire ocean. No laboratory could reproduce such conditions. It was up to him to form and measure a reality as they descended.

What actually happened to the light as they fell?

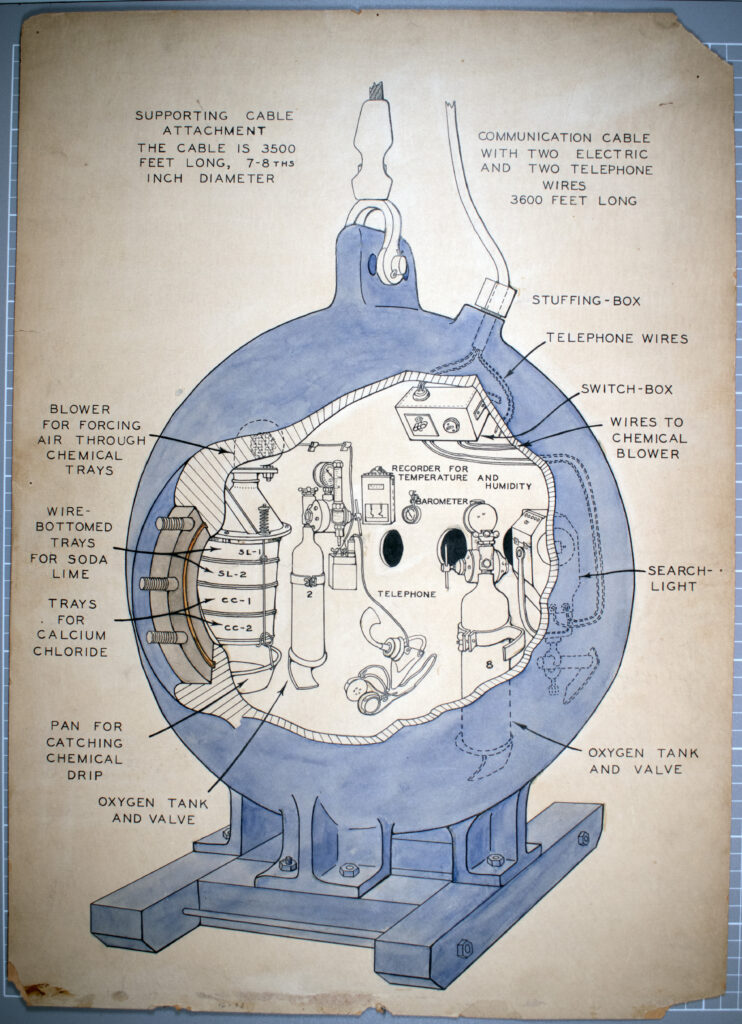

Beebe had the inside of the bathysphere painted black, and on the next dive, he resolved to pay close attention to changes in the spectrum of visible colors. He did this with the help of a spectroscope—a small telescope-like device with a prism, lens, and meter registering values—and by holding up color cards, trying to match what he saw with his eyes.

Hollister was back on deck to record Beebe’s observations, which began as soon as the steel ball hit the water:

Surface red dimming

20 ft Thin line of red, mostly orange

gone from 700 to 650 reading of

spectroscope. See hull plainly.

50 ft. Red absolutely gone. Orange at 625. Other

bands as usual. 3 big Bonito-like fish about

15 inches long

100 Orange much narrowed at 600. Rest of spectrum normal

but dim.

200 No orange present, faint yellow; less green

than at the surface, less blue and more violet.

250 Violet and blue same as above.

Green dim but almost as wide.

Rest dirty yellow with brown edge.

300 Psenes silvery white with no blue at all.

Whole spectrum dim.

Yellow-green almost gone,

its dirty brown edge towards red end.

Violet narrower than at the surface.

350 Brown edge of green gone completely.

50% of spectrum blue-violet, 25% green,

25% colorless pale light.

Red all gone.

450 Still see #30 at lowest aperture faintly.

Blue all gone. Nothing but violet and faint faint green.

3 Eels. 4 Cyclothones in light, but

absolutely invisible without it.

500 Every color of spectrum has gone except violet.

If I didn’t know there was green at the other end, I

could not have named it. On circular color chart

there is not any color that can possibly be named.

600 Two Pilot fishes.

Color still dim. No color.

700 Thermometer a little above 70 degrees

Light light glow where violet was.

Fading off on each side toward the blue.

No color whatever.

When Beebe read these notes later, he found them frustrating. They made no reference to the actual impression of the color. The bathysphere descended to 800 feet, where again he could register no color using the spectroscope. But when he looked outside he saw the deepest black-blue imaginable. He thought of it as something beyond language, requiring a whole new system of descriptors. It was “a solid, blue-black world, one which seemed born of a single vibration.”

When people asked Beebe how low he hoped to go, he always told them something specific—a quarter mile, a half mile. But really, he admitted, what he wanted was to go deeper than the sun’s rays. The horizon of his desire was a step beyond solar light.

On September 22, 1932, he and Barton sank lower than seventeen hundred feet, and when Beebe held the spectroscope, it showed no glimmering of light. Outside it was black with no hint of blue.

He set down the spectroscope and bathed in darkness. No waves at all. That’s what he’d wanted.

Except for the dull and lessening power of the spotlight, the only visibility was provided by the animals themselves, oxidizations of luciferin and luciferase casting their glow of desire.

Facing away from Barton, whose fiddling and whose breath he could still hear, Beebe faced the encompassing blackness out the window. Memory of all other colors fell away and he lolled in the inarticulate shine. There was no explanation and it illuminated nothing.

__________________________________

Excerpted from The Bathysphere Book: Effects of the Luminous Ocean Depths by Brad Fox. Copyright © 2023. Used with permission of the publisher, Astra House. All rights reserved.

Brad Fox

Brad Fox is a writer, journalist, translator, and former relief contractor living in New York. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, The Paris Review Daily, Guernica, and other venues. His novel To Remain Nameless (Rescue Press, 2020) was a finalist for the Big Other Fiction award and a staff pick at the Paris Review.