A Secular Sacrament: Domenica Ruta on Terminating a Pregnancy

“What I desire now more than anything is that feeling of control I first discovered in my abortion.”

“Do you know why they say there is so much breast cancer in the United States?” the nurse asks me. A small medical device like an ugly sadistic broach pierces the skin just above my heart. It hooks me to several bags of chemo, including one known colloquially as the “red devil,” that have been dripping into my veins for hours. I am a captive audience if ever there was one. And I have breast cancer, so yes, I want to know.

“Because of all the abortions,” the nurse says.

“That’s not true,” I snap, fury on a taut leash. Once upon a time she would have scared me witless, but I know in my body what is true. I always have, though it took time to get here.

*

Access to safe, affordable legal abortion freed me from the burden of raising a child at a time when I was too young, too alcoholic, and too broke to do it. It allowed me to continue living an adventurous life of interesting temporary jobs while I was figuring out what it meant to be a working artist. It made space for me to leave a relationship with the man I was dating at the time, years afterward, without the lifelong tether of joint custody to complicate things for either of us.

The socioeconomic impact of abortion cannot be overstated, but for me, it engendered a transformation that I think of as sacred. In another universe, another life, abortion would be a secular sacrament, bloody, holy, a threshold that people could walk through on the way to becoming the person they were born to be.

For the first two and a half decades of my life, my body did not belong to me. I grew up with a narcissist mother who gouged away any and all boundaries between herself and me to such an extent that I still find myself, decades later, a mostly self-actualized adult, picking tendrils of her flotsam out of my hair. During this childhood under her reign, I was sexually abused by a trusted adult, a firebomb to the central nervous system, to any sense of bodily safety. “If I feel this I will die,” I thought in the wordless lizard stem of my brain.

And I lived. I wrote my spelling words three times each, I cleaned my parents’ ashtrays and folded the laundry, I watched thousands of hours of television, I grew up. To do that—live—I had to elect a hazy mental erasure, though this, like so much else, didn’t feel like a choice. My mind, like my body, was something I had no control over; it did what it wanted, remembered what it wanted, blacked out what it wanted.

For years and years it was like this. Things happened to me. I got my period, a passive reception, inevitable and shameful. I threw away my underwear at those first streaks of blood, as though this could make it go away and never come back. When I realized I was powerless to stop it, I tried to hide it from my mother. I failed, and she humiliated me by telling everyone she could. Hair just grew all over my pale skin, not in the downy light brown and neatly contained areas like other girls but black, coarse, persistent, growing back less than a day after I shaved.

I had sex as a teenager (luckily enough by choice, sadly in a world where such autonomy is considered “lucky”), but having is not the same as doing, because first, there was a rotating cast of good and awful boyfriends to whom I was always ceding control, then there was that moment when I took off my clothes, when someone touched me, and little earthworms of repressed memory wriggled into the bed, mucking up the sheets, exposing to my partners, to myself, what trash I really was. I never touched myself. The thought didn’t even occur to me. How could I? All this stuff hanging off my head, my body, that wasn’t really mine to touch. That wasn’t really me.

Until my abortion my body existed in three states—hated, terrorized, or numb. What little agency I believed I had I used in pursuit of numbness. Here was a thing I could do, an action I could take: alcohol, Benzos, opiates. Anything from the family of downers was my chosen family. They didn’t make me feel good. That was never the point. Drugs and alcohol gave me something more important than pleasure—relief. Once relieved of all the fear and pain, the nagging questions, the shame, I could do anything. I was free.

Then, at twenty-four years old, having avoided gynecologists for years and trusting foolishly in the precision of my menstrual cycle, I got pregnant. This was the final betrayal. I was enraged. My stupid disgusting body, never following orders. As soon as I saw the positive pregnancy test I went and bought a pack of cigarettes. I had quit smoking two years earlier, and those first drags made my head feel both bludgeoned and detached from my body. I sat smoking on my windowsill, looking at the dumpsters in the alley below, on that horrible edge of needing to vomit but holding it back. “I hate you,” I said out loud to my stomach. Not to the blastocyst inside but to everything surrounding it.

My mind, like my body, was something I had no control over; it did what it wanted, remembered what it wanted, blacked out what it wanted.Again, I was lucky, and again, it is utter stupidity that we still live in a world where a totally normal, safe, affordable abortion should be considered lucky. But I was particularly lucky, because Boston’s central branch of Planned Parenthood was a short walk from my apartment. I passed through the metal detectors, still lightheaded from my first cigarette in years, and got an appointment on the spot. The staff there was professional and kind.

After taking another pregnancy test I was assigned a counselor, a woman a little older than me but lifetimes away in term of coolness. She had short bleached blond hair with deliberately dark roots, pierced and tattooed at a time, the early 2000s, when not everyone was pierced and tattooed yet. She was beautiful and sexy and looked like she actually ate food when she was hungry, like she did whatever she wanted on her own terms because it felt good.

When I told her I was certain I wanted this abortion, she did the most amazing thing: she believed me. I was so used to doubting and numbing and repressing my own feelings, let alone desires, that her calm acceptance of me at my word was revolutionary. A new way of existing became possible, even if I didn’t know what that meant yet.

She presented all my options for terminating a pregnancy with perfect equanimity and in a cool and empathetic way asked me how I was feeling. “Honestly,” I said, “I feel bad about not feeling bad about this.” Lots of women she worked with felt the same way, she assured me, invoking that magical combination of words where all healing begins: you are not alone.

The method I chose was a combination of misoprostol and mifepristone pills, known then as the French abortion. The counselor told me it was 97 percent effective, noninvasive, relatively painless, and that I could do it myself at home. She encouraged me to stock up on ice cream and other treats and rent some movies beforehand, which proved to be the wisest of prescriptions, then sent me home with a follow-up appointment scheduled for a week later. Because of my income at the time, the whole thing cost me around fifty bucks.

I did exactly what she said. I told my boyfriend what was happening and that I wanted to be alone, so he made himself scarce while I watched documentaries and comedies, ate Thai food, and napped. I bled enough to know that the pills had worked but not so much that I was scared something was wrong. I didn’t feel like running a marathon but I experienced no pain. All in all it was blissfully ordinary, just a pleasant Saturday alone with myself, alone with my body.

*

For years I chased what I thought was relief through drugs and alcohol. If there was anything I desired it was that escape. I now know that what I had wanted all along was control, and getting high offered a believable substitute. The equation was deceptively simple. Drink this, wait twenty minutes, feel better. Snort this and seconds later feel something new, something I bought and paid for, something I chose. It worked well until it didn’t. At a certain point in my progressive alcoholism, I could no longer manipulate the formula for the desired effect. My body had betrayed me again and then all I wanted was to die.

I’ve spent the past thirteen years in recovery from addiction. As passive as abstention seems on the surface, sobriety is a conscious daily rejection of both the passivity and the delusion of control I found in drinking. It requires work, lots of it, and a fearless consciousness of myself and my desires inside that work.

I have to choose to be sober every day, which is another way of saying I choose to be here, in this life, in this body: the one where I am pregnant with my first child, opting for single motherhood over a more traditional life with a partner who is not right for me; the one where I am pregnant with my second child, conceived on purpose with a partner I loved enough to marry; the one where I am telling the surgeon that I don’t want a lumpectomy, I want to remove both my breasts, because they are mine and I get to decide what happens to me; the one where I am fighting for my life in a little cubicle of the cancer center, hooked up to all those bags of chemo, immobile but no longer powerless, telling the nurse with the sureness of everything in my body that no, abortion does not cause cancer.

*

Love can be just as excruciating as fear in the body of a trauma survivor and reality in all its vagaries is fucking bleak even in the best of times. Despite all my growth, all my tools, what I desire now more than anything is that feeling of control I first discovered in my abortion. I want the power I felt then, the knowledge that my body would do exactly what I wanted it to do. I would happily sign away all my money, forgo every word I will ever write, give up all sex and bliss for the rest of my life to know that I had the same control over my children’s bodies in the way I had of that first pregnancy. I want the power to ensure that they will never get sicker than I have the ability to cure with the generic syrups I have in my bathroom cabinet, that their bodies will never be broken by a careless driver, or a falling air conditioner on a New York City sidewalk, or the craven gunshot of a racist cop.

Give me a 100 percent guarantee that no human being will ever touch their bodies the way my childhood abuser touched mine, that they will only have sex when they want to, and that it will never feel shameful and frightening to them in the same greasy, sinister way it can sometimes still feel for me. I want them both to explore our planet, or what’s left of it by the time they are adults, and feel nothing but a combination of curiosity and compassion for the life that surrounds them, instead of the dogged anxiety that follows me to this day, whispering mostly, sometimes screeching, “You will never be safe, not in that body of yours.”

I want that, forever—the power of choice not as microcosm or metaphor in a Planned Parenthood office but a discrete and tangible act, a bloody rite, a routine procedure I can undergo that will allow me to keep my family whole and happy, sane and productive, adventurous and safe, for the eight or so decades I feel is our due. I want control, both inside and surrounding us, a magical placenta where we have not only the right but the power to choose what happens to us.

The work of smashing my delusions never ends. Life makes sure of that.

The week my second child was born, the death toll for the Coronavirus was at its peak in New York City, where we live. I walked into the hospital with a plan for how this baby would be born—as naturally as possible, at his own pace and mine—but the hospital staff had other ideas. A nurse whose face I never saw because of our masks told me that yes, my birth plan was wonderful, realistic even, but not today, not with a pandemic and morgue truck parked outside. They were going to force me to have this baby as quickly as possible, which meant administering Pitocin, which meant getting an epidural, all the things I was hoping to avoid.

If abortion taught me for the first time that I had control over my own body, childbirth taught me how to let go of that control, and cancer was a lesson that neither of those things, control or surrender, are mutually exclusive. So I did what the nurses said. I agreed to their plan. My baby was born, an act that was both totally mine, of my body alone, and in collaboration with forces outside me. Something I did, something that happened to me, happened to us.

__________________________________

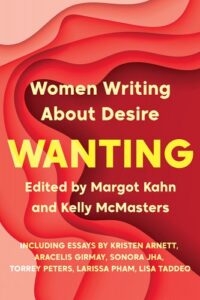

Excerpted from Wanting: Women Writing about Desire, edited by Margot Kahn and Kelly McMasters. Copyright © 2023. Published with permission of Catapult Press.