A Room Without a View: How to Create Space (and Time) for Creativity (on the Toilet)

Daniel Wallace on His Father’s Writing Space

My father taught me how to write. Not to write, but how to create the space and time where a moment of inspiration can be captured and made real on the page through language.

He would be saddened to know he had this affect on me. He never wanted me to write books; he wanted me to come to work for him and write invoices. It was tempting. He was a successful importer of things, a jaunty world traveler, with a jet and many homes. Enticing, his life, but I decided to become a writer instead, and the result of that decision, made in 1983, meant years of icy distance between us. We were beginning to warm to each other again when he died, in 1997, a year before I sold my first book.

One of the prerequisites to becoming a writer is, I think, a love of language, of words, plain and simple. Every family has its own idiom, peculiar expressions that aren’t necessarily unique to it but feel unique, a linguistic identifier, and they can brand you.

This too I inherited from my father. He had a lot of those expressions.

That and fifty cents will get you a cup of coffee.

Makes no difference if he is a hound, better quit kicking my dog around.

Champagne taste, beer pocketbook.

Doesn’t know his ass from deep center field.

These are all expressions I attribute to my father, even though he didn’t make them up, one of a million to use them. If I left the front door open, allowing the air-conditioned inside to flow into the hot and humid outside, he would ask me if I was “born in a barn.” I love this expression now, and the idea that I might have been born in a barn, and that somehow being born there made me incapable of closing the door to a real house. It didn’t make any sense, but still.

Another: You could screw up a one-car funeral. This was a favorite of his and while I understand what it’s supposed to mean—I messed things up, a lot, who doesn’t—I could never understand how this really works, the significance of a funeral this small, or in what way I could possibly have anything to do with one and what I could do to ruin it.

But surely his most beloved expression was this, the vulgar version of Fish or cut bait. Which is this: Shit or get off the pot.

There was no limit to the number of life-moments this expression could be applied to. It can mean take action! Which is the positive take on it. Or it could be read as more critical, meaning take action or forget about it, move on, give someone else a chance, I’m sick and tired of you not doing anything around here.

Here’s the thing: my father traveled a lot. The sad anonymity of hotel rooms blocked him up. He missed the comfort of home, and so, when he returned, he went to the bathroom. This is where he went when he came home, and where he stayed, for a good long time, until he left again on business. He had a real office a few miles away, but at home the bathroom was his office, and, not unlike Lyndon Johnson, he had an open-door policy for us all; in fact, the door was rarely closed.

Anyone—me, my sisters, my mother, the maid—could, and did, walk past the bathroom and see him there, sitting on the toilet, light blue boxer shorts collapsed around his ankles, hiding the tops of his feet, hairless and white. His back was hunched forward, and his elbows were resting on his knees. In his hands were six or seven squares of yellow toilet tissue, which he folded, unfolded and folded again, carefully at the perforations.

Most of the time he sat like this, staring at the tissue, a thoughtful, sometimes anxious expression on his face. To one side was the bathroom sink, and on the tile beside the sink was a cup of steaming hot tea. He didn’t wear his wristwatch but had it sitting beside the sink, and would check on the time now and again while he smoked his cigarettes, Benson & Hedges, cigarettes that scarred the bathroom tile as they burned when he balanced them there for too long. The toilet was his ashtray. If the cigarette was extinguished during a quiet time, you could hear the red-hot ember—the rock—splash and sizzle in the water.

The deep acoustical echo of my father’s voice, calling out: I will never forget that.

On the floor near his feet were a yellow legal pad and a gold Cross pen. My father made notes to himself, drew pictures, added and subtracted three- and four-digit numbers, or he made lists of things to do. But these things, unless they could be accomplished from his seat on the toilet, remained undone. Odd jobs, household chores, errands and family outings all placed a distant second. This, his time spent here, was the important thing.

Still, even under these strange circumstances, it was easy to gain an audience. If you had some specific need or desire to speak with him, he would accommodate you. He would listen to whatever you had to say, and respond accordingly. Sometimes he was otherwise engaged, and at these times conversations were understandably kept to a minimum.

But if he hadn’t made any “headway,” as he put it, one might spend as much as three or four minutes in there chatting with him. He called out sometimes—for the newspaper, cigarettes, another cup of tea. The deep acoustical echo of my father’s voice, calling out: I will never forget that. It was also possible simply to pass the bathroom and take a look in, see how he was doing. Sometimes he wouldn’t notice, so involved was he with his tissue folding, and thinking, and making notes. But other times he’d smile and wave, and ask what’s up. Not much, you’d say. How about you? Not much, he might say. Not much at all.

And so went his day. When he got a telephone call the cord was stretched to the very end of its length. Through the morning my father talked on the phone, read the paper, took notes, doodled, smoked, drank, and folded his soft yellow squares of toilet tissue while thinking about something—possibly me; I mean, why not me?—until, finally through for the day, he depressed the small metal handle there, and the rumbling roil of the churning water full of all the crap he could fill it with began. You could hear it in the pipes.

“Done!” he proclaimed, standing, taking a breath in deeply. Then he washed his hands beneath a stream of hot water, glancing up at his reflection in the mirror, pleased. He was pleased because the job he had come here to do had been done. After a long, possibly arduous day he could look at himself and say he had achieved his goal.

The next day he would be there again, and then the next or possibly the next, he would be gone on a trip, sometimes for weeks.

We don’t learn from people telling us things. We learn by watching them. We learn from experience. Long before I knew it was even happening I had started to become a writer, which is the way it is with most things: we start long before we know we’ve started, and only by looking back can we tell when the beginning really was.

Because I didn’t know for a long time that the one indispensible thing I learned about writing I learned from him. That all you need is a pen and a piece of paper, a cup of tea, a small room where you can get some privacy when you need it, and a comfortable place to sit. And then you don’t move. You sit there until what you came there to do gets done. And then wake up the next day and do it all again.

__________________________________

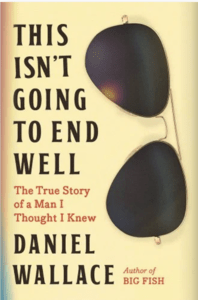

This Isn’t Going To End Well by Daniel Wallace is available now.

Daniel Wallace

Daniel Wallace is the author of six novels, including Big Fish, which was adapted and released as a movie and a Broadway musical. His novels have been translated into over three-dozen languages. His essays and interviews have been published in The Bitter Southerner, Garden & Gun, Poets & Writers and Our State magazine, where he was, for a short time, the barbecue critic. His short stories have appeared in over fifty magazines and periodicals. He was awarded the Harper Lee Award, given to a nationally recognized Alabama writer who has made a significant lifelong contribution to Alabama letters. He was inducted into the Alabama Literary Hall of Fame in 2022. He is the J. Ross MacDonald Distinguished Professor of English at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.