A Recipe Must Do Many Things: Writing a Cookbook With Chef Kwame Onwuachi

Joshua David Stein on Moving from Cowriting a Memoir to Cowriting a Cookbook

I first met Kwame Onwuachi in August 2016, after he had sold what would ultimately become Notes from a Young Black Chef to Knopf but before the book had taken shape. The editors at Knopf and Kwame were looking for a co-author and called me so I met him on a hot Friday afternoon at the PRH tower in Midtown. Despite the inherent weirdness of the meeting—it’s like a first date but observed, high stakes and professional—we hit it off.

One reason, I think, is because since I’d been around and writing about chefs for so long, I didn’t relate to him as a Bright Up-and-Coming Chef, which he was, but as a human being, as I came to find, a wonderful human and wonderfully complicated human being. This, the actual seeing of another person, is perhaps the most necessary thing as a collaborator and one reason, I think, why Kwame and I have worked so well with each other for so long.

Notes started as one thing and became another. When we began work on it, Kwame was in the midst of opening Shaw Bijou, his first fine-dining restaurant in Washington D.C. The general trajectory of the narrative was a steady triumphal slope upwards. (The original title was Chasing Happiness.) Naturally, as a writer, I worried about this. I knew immediately one of my challenges would be to help Kwame see—and to admit to and to explore the idea—that a) that smooth line was probably not an accurate representation of his life’s path and b) a compelling memoir a smooth line does not make.

As it turns out, we didn’t have to work too hard to manufacture a more nuanced arc after all. Shaw Bijou closed shortly after it opened under a hail of criticism. As Kwame’s friend, I was gutted. But as his co-author, I was in some ways relieved. Notes couldn’t help but be more interesting, more human, more relatable, after it grew to include this setback. One reason that book resonated with so many readers is that it didn’t shy away from portraying the self-doubt, the challenges, the insecurities all of us face in one form or another without appending an artificially rosy conclusion to it. Kwame’s story is Kwame’s unique story but it also resonates in a universal way.

As Kwame’s friend, I was gutted. But as his co-author, I was in some ways relieved. Notes couldn’t help but be more interesting, more human, more relatable, after it grew to include this setback.

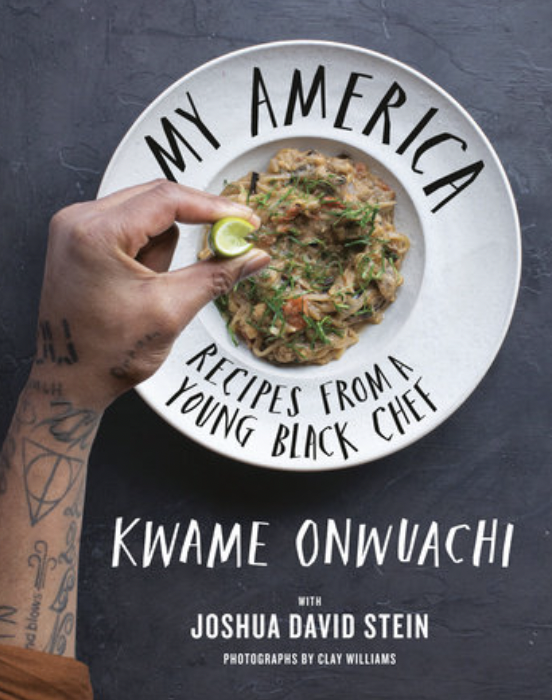

By the time we started the cookbook, My America: Recipes from a Young Black Chef, Kwame’s life had grown more complicated and expansive. Notes had been a success and had helped situate Kwame in a broader cultural context. The book had gotten picked up to be made into a movie, starring Lakeith Stanfield as Kwame. (Who plays me? I wonder!) Kwame was fielding many offers for many projects. He was living in Los Angeles—Hollywood, I think—and was no longer tied to a restaurant. I, however, was still in my apartment in Brooklyn, hustling.

In the intervening years, I had written a slew of cookbooks (The Nom Wah Cookbook, with Wilson Tang; Il Buco: Stories & Recipes, with Donna Lennard; Vino: An Essential Guide to Real Italian Wine, with Joe Campanale; Cooking for Your Kids) and a few children’s books (The Invisible Alphabet and Solitary Animals). I was generally and still very much hustling. Our lives had taken somewhat divergent paths. And yet we were both very excited to work together again, especially on a cookbook. Though Notes had some recipes, it was overwhelmingly a prose-based text. Prose being my wheelhouse, my hand was felt in wrangling Kwame’s stories for the page. But in a cookbook, recipes are the central mode of communication. Recipes being the thing as which Kwame excels, we were both excited to take advantage of this new form.

The processes of writing a memoir and a cookbook aren’t that different. In either case, one must find the idea that animates the entire project. Sometimes that idea is waiting at the threshold of the project, ready to welcome you in and show you around. Sometimes that idea doesn’t become clear until later on. I view my task as a co-creator—not just with Kwame but with all the authors with whom I work—to help sharpen, refine and reveal this idea so that it shines as brightly as it can, offering both illumination and direction to the work.

In My America, Kwame naturally wanted to express his story—and the story of his family—through recipes and this meant going both deeper and wider. Whereas Notes had been primarily about his own journey from child to chef, My America expanded the scope from his own personal journey to the journey of the generations before him. My America combined essays and headnotes with over 125 recipes. As any cookbook author will tell you—and as any cookbook reader knows—the recipe must do many things. The ideal recipe is appealing, actionable, and expressive. It must answer what and how, of course, but also why? Why is this recipe from all the others that could be made fit here, in this book?

We created the recipe list that encompassed the sort of diasporic cuisine that ran through Kwame’s family tree and tested it. For that year, this food kept me fed. Confined largely to my house by the pandemic, it was a lifeline.

Working with a wonderful team that included David Paz, Kwame’s right hand man, and Caroline Lange, a top-notch recipe developer, we created the recipe list that encompassed the sort of diasporic cuisine that ran through Kwame’s family tree and tested it. For that year, this food kept me fed. Confined largely to my house by the pandemic, it was a lifeline. I, like everyone else, had adopted a pandemic doggie, a rescue from Puerto Rico who came named Hermione. Caroline, who lived not too far from me in Brooklyn, would drop off a carefully labeled bag of recipes she had tested at the dog park. Thus it was that the height of COVID was softened with crawfish pie, buljol, fufu, moimoi and Mom Duke’s Shrimp.

Every week, Kwame and I would meet and he would walk me through the story of each recipe. More often than not, these stories were personal to him: memories of eating, for instance, Groundnut Stew with his mother in Le Petit Senegal in Harlem. And then I would combine that embodied knowledge with research, tracing, for instance, how the groundnut made it to Africa in the 1500s from Brazil, flourished in West Africa and then came back to the United States aboard slave ships.

Just as how during Notes, we pushed each other to make connections perhaps otherwise left unsynased, so too in My America did this combination of augmenting Kwame’s lived experience of his food with my researched knowledge connect the dots for us between, for instance, Nigerian jollof and Creole jambalaya. As we write in the introduction, “They are not islands but part of the same river.”

By March the text was in good shape. Clay Williams had shot the book beautifully and we were in the home stretch. The only thing missing was a title. On one hand, Kwame was a big enough name it could, conceivably, be called Kwame. But this wasn’t just his story anymore. And while it was diasporic cuisine, that title was too both too broad and too narrow. We had barely touched South America or North Africa or a thousand other lights of the diaspora’s reach. Further, much of Kwame’s food isn’t what you would call traditional. It’s a heady blend of technique and ingredients that could only happen here and with him. And that’s where we landed: My America, an America made up of many voices, streams, rivers, spices, ingredients, joys, sadnesses and recipes.

______________________________

My America: Recipes From a Young Black Chef, by Kwame Onwuachi and Joshua David Stein, is available now from Knopf.

Joshua David Stein

Joshua David Stein is an author and editor. Among his works are Notes from a Young Black Chef and My America, with Kwame Onwuachi; the Nom Wah Cookbook, with Wilson Tang; Il Buco: Stories & Recipes, with Donna Lennard and the cookbook Cooking For Your Kids. He is also the author of many children’s books, most recently of Solitary Animals: Introverts of the Wild. He lives in Brooklyn, NY, with his two sons.