A Real-Life Fitzgerald Hero, Too True for the Jazz Age

On Hobey Baker, and the Beginning of the American Century

Unless you’re a hockey nut or you went to Princeton, you probably haven’t heard of Hobey Baker. Timing is everything, and history has a way of obscuring people who were born for the wrong age.

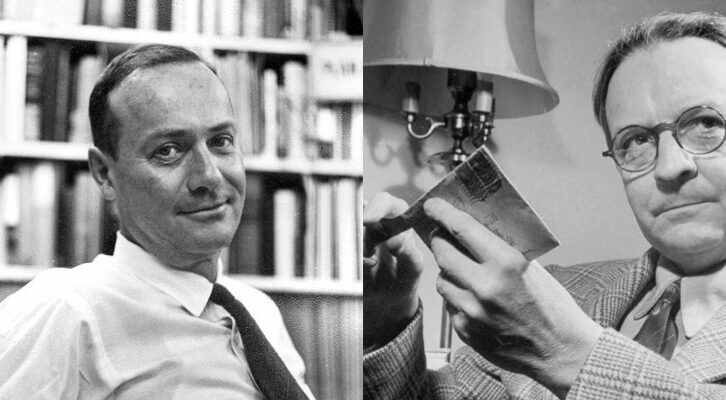

In his day, though, everybody knew Baker. He remains the only man inducted into both the College Hockey Hall of Fame and the College Football Hall of Fame. He was a freak of nature, an athletic genius who—like the fictional Graham Pendleton in my novel A Hundred Summers—excelled “at all sports, even the ones he hadn’t tried yet.” Except Baker was the real deal, a golden-haired Adonis who never wore a helmet, modest to the point of self-effacement, a gentleman who adhered to such fantastically archaic codes of sportsmanship that the one time he earned a penalty in a hockey game, he afterward visited the opposing team’s locker room to apologize. The newspapers worshipped him. So did F. Scott Fitzgerald, a Princeton freshman during Baker’s senior year. The godlike football hero Allenby in This Side of Paradise is modeled after Baker, and Fitzgerald bestowed Hobey’s middle name—Amory—on the main character, a thinly altered version of Fitzgerald himself.

But Hobey Baker, who graduated Princeton in that watershed year 1914, was not made for the modern world. Offered dazzling stacks of cash to turn professional, he declined. Games, he believed—take note, Christian McCaffery—should be played for love of sport and school, not for money, and the professional athlete was a disgrace to athletics. So he embarked on a dutiful Wall Street career after college, like you do, but his heart remained on the playing fields, locked in honorable combat. When the United States finally declared war in 1917, he jumped to attention. Having already trained as an aviator during his spare time from the office, he joined the United States Army Air Service and, by the second week of November 1918, had four confirmed “kills” on enemy aircraft, one short of ace designation.

Then the war ended.

Now, imagine for a moment that Captain Hobey Baker returns to New York at the dawn of the Roaring Twenties, the Decade of Disillusionment, the Jazz Age. He slips back into his Wall Street office, marries someone suitable, watches the old code of manners and morals crumble around him, finds (as Fitzgerald observes in This Side of Paradise) “all Gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man shaken.” There’s a novel there, but it’s not a happy one. There are no heroes in it. In four black years, the world had moved on from idealism to realism, and the very notion of heroism was now a quaint, laughable relic. Thinking people didn’t write or read or sing about heroes. Virtue was a joke. There was no point in aspiring to an ideal, or in creating ideals to aspire to. That was all a racket for the masses. “And so,” as Frederick Lewis Allen wrote in 1931, in his brilliant history Only Yesterday, “the saxophones wailed and the gin-flask went its rounds and the dancers made their treadmill circuit with half-closed eyes, and the outside world, so merciless and so insane, was shut away for a restless night.”

And that’s the challenge with writing books set in the 1920s: there’s hardly anyone to root for. The stakes are so meaningless. Prosperity arrived, crazes came and went, Babe Ruth hit some home runs, Lindbergh flew across the Atlantic, and what for? Even the villains were a kind of anti-hero, sticking it to Prohibition. Any good, true fiction set in the decade can’t be satisfying, and yet people want satisfaction. It’s in our blood. We are made uneasy by dangling threads, by stories left unfinished, by evil left unpunished, by the imperfect segregation of good and evil. We want closure. We want to be right. We want to fight something and win.

The Depression came, the Nazis came, and though the years became black again, fiction regained its purpose. You could draw lines, you could fight something real, and the world begged for its heroes back. By then, Hobey Baker was long gone. A month after the Armistice, carrying his discharge papers in his pocket, hours away from his return to New York, he decided to make a final flight—a test flight of an aircraft that had just been repaired—and he crashed to the damp French earth.

And maybe it was an accident. Maybe Baker was just doing what any good squadron leader would do, assuming the risk on behalf of his men. Or maybe he was a prophet who foresaw the years that lay ahead.

The age that had no use for him.

Beatriz Williams

Beatriz Williams lives with her husband and four children near the Connecticut shore, where she divides her time between writing and laundry. Her books include Overseas, A Hundred Summers, The Secret Life of Violet Grant, Tiny Little Thing, Along the Infinite Sea, and The Forgotten Room.