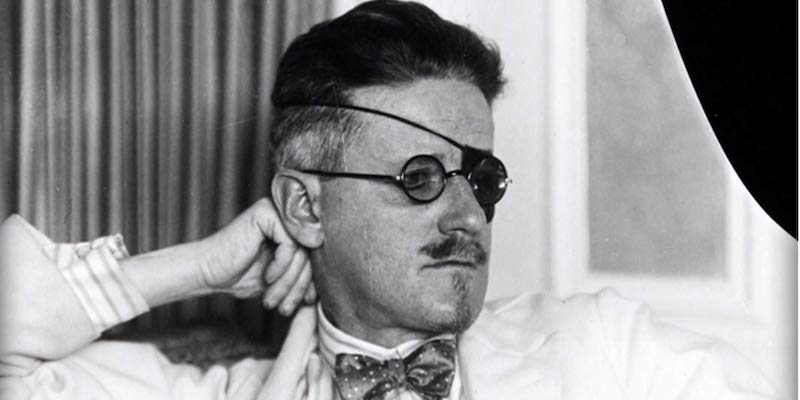

A Queer Reimagining of James Joyce's Ulysses in Northern England

Helen Palmer on Why She Chose 1990s Blackpool for the Setting of Pleasure Beach

The town of Blackpool conjures a particular multisensory reaction that is hard to convey to those who live far away from its sticky seaside scope. Or perhaps it isn’t so hard. Blazvegas: an upside-down Coney Island headrush, a ride that defies gravity, a windswept concrete strip of stalls selling sweets and plastic. A Golden Mile of pubs, clubs, casinos, and amusement arcades. A history of sea-bathing and smut. Stag and hen party heaven.

A hedonism hub, as it is described in Pleasure Beach, the sheer number of ways to get “messed up” within one weekend spent in this town is staggering. So why choose this location for a queer romantic reimagining of Joyce’s masterpiece set in 1999?

The polarization of the two main characters in Joyce’s Ulysses—Dedalus and Bloom, the mind and the body, the son and the father, the Catholic and the Jew—this was something I wanted to reimagine and somewhat dissolve in Pleasure Beach, and most importantly, with female rather than male voices. A queer love story between two young women, Rachel and Olga, and a third interlocutor, Treesa, seemed the perfect way to do this: bodies, minds, desires and intensities flow between the characters and their environment in this place of sensory overload.

Anyone visiting Blackpool now would find it a place of queer celebration and communion: recent research has shown that the town has the highest number of trans young people in the U. K. Gender multiplicities and all type of relationships are affirmed in Blackpool’s contemporary environment, albeit sometimes with a brazen northern English charm offensive that in Drag Race terminology would be such a thorough “reading” that a whole new department of the library would have to be built.

On 16th June, 2023, we launched Pleasure Beach in Blackpool on its very own Bloomsday. Late into the night in a gay bar, the collective and individual heckling that our group endured from a local DJ drag queen for being a group of international “lesbians” in that space was incredible: quickfire, hilarious, scorching. Far from being designed to injure it was part of an ancient code that says: welcome, you are one of us.

The sea here is everything. It is vital to point out that the “snotgreen” Irish Sea which laps on the shores of Sandymount Strand in Joyce’s Dublin is the very same Irish Sea which laps on the long stretches of Blackpool’s own sands. As a prime location for convalescence through “taking the water” in the nineteenth century, the sea is the original historical-geographical reason for Blackpool’s existence. The Irish Sea connects the two places and is vital to both places’ imaginaries.

The polarization of the two main characters in Joyce’s Ulysses… was something I wanted to reimagine and somewhat dissolve in Pleasure Beach, and most importantly, with female rather than male voices.

Joyce’s “scrotumtightening sea” becomes the “organgrinding sea” in Pleasure Beach: a nod to non-binary corporealities as well as the old-fashioned image of the organ-grinder, the entertainer playing the barrel organ on the streets. As I wrote about in my book Queer Defamiliarization, the most famous organ of Blackpool is the Wurlitzer organ to be found in Blackpool’s Tower Ballroom. This organ playing the traditional song “Oh I Do Like be Beside the Seaside” is the quintessential Blackpool sound.

I have long considered that organs occupy a central position in Blackpool’s cultural history, and organs of all kinds: from instruments to bodily components. The monolithic tentacle which now adorns the Blackpool Promenade is a sensory organ and a musical instrument: a High Tide Organ or sea organ, played by the tides as they rush in and out. The focus on the body is something I wanted to develop from Joyce’s rendering of it in Ulysses.

Joyce turns readers into voyeurs as we witness Leopold Bloom’s intimate bodily organs, expulsions and emissions, from his ejaculation while watching Gertie MacDowell on the beach, to the “languid floating flower” of his penis floating in the bath, to the sound of his flatulence which he masks by timing it exactly with the passing tram. For a queer feminist reimagining of such embodied writing, it felt fitting to place the story within a town where bodies of all shapes, sizes and levels of sunburn are on show, but also the flows, surges and hormonal fluctuations within the body’s cavities.

My adaptation of Joyce’s schema for the novel adds new categories to his existing list: in addition to each chapter illustrating an organ of the body, for example, my own schema also contains a hormone, a substance, and a ride at the Pleasure Beach theme park for each chapter. The hormones in particular are important because they themselves are the tidal surges that course through the body and its organs, causing ebbs and flows of feeling. This is the internal Pleasure Beach that I wanted to create in the book: the rollercoaster of human experience, spoken through the chemical messengers inside the body that determine how we feel.

If it is bodies in Blackpool we are talking about, then, both insides and outsides are important. The famous Glasgow meteorological expression of “taps aff” (translation: a temperature hot enough that men walk around with no T shirts on, which in both Scotland and northern England is usually around 15 degrees C / 59 F), is just as applicable in Blackpool due to the massive influx of Glaswegians who have been coming down to Blackpool for decades to party. Between sunbathing bodies and groups out on the razz and dolled up to the nines (translation: partygoers dressed up ready for the pubs and clubs), it is impossible to escape bodies and skin.

In Pleasure Beach my aim was to go beyond the skin, to not stop at the surface and to get underneath. I wanted to imagine what happens inside the body’s bloodstreams and organs when cigarettes are inhaled; when enough sugar is consumed to produce a sugar rush; when alcohol causes a person to vomit. To my knowledge, vomiting is one bodily expulsion not covered by Joyce in Ulysses, and it is something that happens several times within the twenty-four hours spanning Pleasure Beach because it would not be Blackpool otherwise.

With rollercoasters that project you up into space and back down again within seconds, whirling waltzers and upside-down loop-the-loops, added to vast amounts of greasy pier food and alcohol there are, as it says in the novel, “more reasons to vomit per square mile than anywhere else in Great Britain.”

Joyce plays with sound and language in Ulysses in innumerable ways. The sounds of words and the words of sounds are ingeniously manipulated especially in his “Sirens” chapter, so the challenge for me was to depict the Blackpool soundscape at the very end of the twentieth century. Pleasure Beach is a continual soundscape that contains multiple genres but is hugely dominated by the commercial late-1990s trance that was playing in the Blackpool clubs at this time.

The utopian promise of early 90s rave culture had been commodified by this point, and this was the point from which I was writing. What we heard in the Blackpool clubs in the late 90s/early 2000s was commercial trance music.

Despite the character Rachel’s rather snobbish comments related to this music as she is overwhelmed despite herself by the frenzy of a choon that is Silence by Delerium, what I hope the novel conveys is that commercial trance carries its own magic, its own euphoric bluster, upon which I myself was carried as a youth in the Syndicate superclub with its epic green lasers and revolving dancefloor. If you know, you know.

Someone asked me if it had been healing to place this queer coming-of-age storyline in my hometown, in my past. The answer was undeniably yes.

Slowly, as the twentieth century proceeded and international travel became more and more affordable, Blackpool lost its glamorous sheen as the premium holiday destination of the North and people started flying off to Benidorm or Magaluf for their jollies. The Irish Sea was polluted in the 90s when I was growing up there, and did not have the safe “Green Flag” status that denotes a sea clean enough for humans to swim in.

Once the main reason for Blackpool’s existence was rendered obsolete, what was left? Hedonism. The pursuit of pleasure for its own sake sounds more romantic than the reality. Excessive consumption of sugar, grease, alcohol and narcotics makes a blast of a weekend, but it is interesting to consider how it feels to live in a place famous for its permissiveness and the forgetting of “normal” life.

A hybrid word I conceived of that didn’t make it to the final cut of Pleasure Beach: the seedside. The seedy underside of the seaside. The naughty things, the sometimes-sordid things, that go on underneath “normal” life everywhere, can be found streaked across Blackpool’s surface. But in Pleasure Beach, there is more than the seedside—there is healing.

Someone asked me if it had been healing to place this queer coming-of-age storyline in my hometown, in my past. The answer was undeniably yes. A queer 1990s Ulysses in Blackpool? It could not have been anywhere else.

______________________________

Pleasure Beach by Helen Palmer is available via Prototype Publishing.

Helen Palmer

Helen Palmer is a writer from Blackpool. She is the author of Deleuze and Futurism: A Manifesto for Nonsense (London: Bloomsbury, 2014, and Queer Defamiliarisation: Writing, Mattering, Making Strange (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press). She is a 2023 Interdisciplinary Resident at the Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Virginia, USA. She currently lives in Vienna. Pleasure Beach is her first novel.