Darren and Vinny were cruising back home, and now, before our Cambo prohs merge onto the 405 and then the 710, where their shadows will be flitting across the very lane where Peou died, it’s worth digressing to pay homage to what awaits them in Cambotown. Given their impending and official mourning, even I have to ask myself: What stream of history were the cousins about to step into, for the first time, as unknowing adults? What invisible current will be knocking them into the rapids of life, and toward what exactly will they be rushing forward?

The first Mas and Gongs to face death in the United States were primarily concerned with accruing enough old-school karma to ensure that nothing as horrible as an autogenocide would strike them in the new reincarnated lives they had ahead of them. In terms of authentic Buddhist traditions, they demanded their funerals be equipped with the works—a whole week of every close relative sleeping together on the floor of the deceased’s home, burning as much incense as possible, an army of monks (even the monks known to be assholes, the ones who greeted templegoers by blowing cigarette smoke into their faces), fulfillment of the divine requirement for grandsons to shave their heads and live in the temple with the monks for at least three days, subsisting on nothing but cold rice and the smell of ash and enough home-cooked food to feed the entirety of Cambotown to nourish both its bodies and ghosts, its past and future souls, its every generation for all the decades to come.

As the years went by, though, it became harder to accommodate these traditions. Some Cambos had second and third jobs to work. Others had become too accustomed to their luxuries of air-conditioning and extra-soft mattresses and premium cable. Sleeping on the ground with thirty other relatives for a weeklong wake was hardly sustainable, especially when so many Cambos were plagued with PTSD-fueled nightmares—or even just sleep apnea—disorders that caused them to scream in the middle of the night, to gasp for air amid their dreams. And as generations of new Cambo-Americans enlarged each family, funeral homes stopped being so lenient. It was one thing, in the 1980s, when a party of thirty Cambos rolled into a funeral home, took off their shoes, and started droning unintelligible chants that rang through the entire neighborhood, but when thirty mourning Cambos increased to fifty, and then one hundred, and then several hundred, it became a different story.

With these difficulties came a lingering doubt that these traditions were worth keeping, a skepticism of whether anyone could actually remember with any accuracy what was and wasn’t in line with true Khmer, true Buddhist, true Cambo-gangsta values, and a disbelief in the entire premise of reincarnation or karma in the face of Americanized teenagers who were taking AP Chemistry and Biology, who learned about scientific concepts, such as evolution and the laws of thermodynamics, on their way to becoming rational, educated members of U.S. society. By the time of Peou’s death, the point of praying for a week straight for the dead, among other funeral rites, had slipped from our grasp, remaining out of reach while still taunting us with its presence, like a fish tangled in a line, thrashing to evade the fisherman’s hands, trying to jump back into the ever-elusive depths of the ocean beyond.

But with this skepticism came a contingent of Ohms, Mings, and Pous determined to combat this loss of culture, to overcome what they saw as an endemic amnesia. This led to impressive feats of overcompensation. The inability to find willing funeral homes to accommodate their needs prompted the tripling of the amount of authentic Khmer food prepared as offerings for the spirits of the afterlife, those poor suckers stuck between death and reincarnation. Plates of prahok were left to rot even further at the base of altars, the stench of fermented fish mixing with the aroma of incense. Parents began forcing grandsons of the deceased to stay in the temple not for the traditional week, but often for almost a month. Once, a friend of mine refused this obligation as a grandson, explaining that he was an atheist and also that he was not about to shave his head just weeks before prom. In response, his mom brought a monk home to live in my friend’s room, evicting him from his own bed for what turned out to be years, as two weeks into this arrangement, the monk decided to forgo his Buddhist calling. “My name is now Bradley,” the monk stated, and naturally, my friend’s mom felt too bad for Bradley to turn him out into the streets.

The next phase in the trajectory of Cambo funerals was open competition. Middle-aged Cambos started throwing funerals the way one would a wedding, say, or a graduation party—lavishly enough to prove they were better, richer, and more enlightened than the rest; not only were they the most Cambodian, but they also had the money to actualize this Cambo-ness. One year, a family hired a live band to accompany the Buddhist chants intoned during prayers. Another family flew famous monks straight from the homeland to grace Cambotown with the authority of their presence, the authenticity of their blessings. At the funeral of my second cousin’s Gong, the eldest son of the deceased supposedly paid thousands of dollars to import supposed holy water from the secret wells of Angkor Wat. That same eldest son ended his eulogy for his beloved mother by forcing this holy water down his own throat, which sent him straight to the bathroom, where he stayed for the remainder of the funeral, shitting his brains out.

Planning a Cambo funeral, this is all to say, meant plunging into a deep chasm of conflicting cultures and shifting value systems, forced assimilation to standard American practices, superstitious paranoia about karmic destinies tempered by a burgeoning nihilism toward a universe that allowed millions of Cambo deaths, and competitive one-upmanship to prove the prominence and economic legitimacy of one’s family unit. Imagine, then, the anticipation, the buildup, the utter trepidation thundering through Cambotown when it came to planning Peou’s funeral. She had been the underlying adhesive keeping Cambotown together, after all, the very lynchpin of the Circle of Money.

It would have to be the funeral of all funerals, the party of the year, and in planning this event, Peou’s older sisters drove themselves, each other, everyone around them absolutely insane. Not only did Ming Won and Ming Nary have to worry about traditions, honoring Peou’s deep legacy, preparing food for hundreds of guests, and trying to determine whether they trusted Darren and Vinny to stay in the temple without embarrassing them, even as they coped with their own grief and pulled together the thousands of dollars to cover the funeral costs, but they were also well aware of the fact that every Ming and Ma in Cambotown was now hovering over them, waiting to sink their teeth into each minor mistake, before shaking their heads and whispering, What a shame. Peou deserved better than what those two sisters call a funeral.

__________________________________

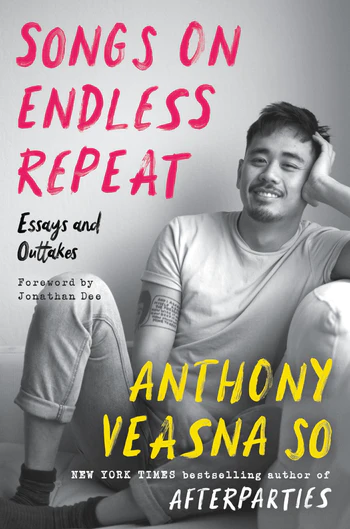

From Songs on Endless Repeat by Anthony Veasna So. Copyright © 2023 by Ravy So and Alexander Gilbert Torres. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.