A New Life or a Different Death? How Immigration Splits the Self

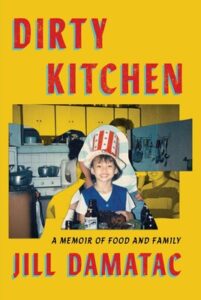

Jill Damatac on the Timeless Paradox of Leaving Home For a Foreign Land

The first time I cleaved from the earth and saw oceans, I was nine. We left the Philippines six years after the end of the His and Hers Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos. Hidden by night, Mama, my three-year-old sister, and I traveled by airplane. We arrived at our final destination after three airplanes and thirty hours in the sky. We went back in time by one mortal day, August 13, 1992. The longest day of my life, in both time and space.

Lay the sangkalan, ideally made of strong sampalok wood, on a flat surface.

On that journey, I saw the dawn gate in the east, the one between sky and sea, where all life begins. Where gods and spirits are born. As each day begins, they stride across the heavens on wind-light feet, cloud to cloud. They walk westward, towards death, the dark gate at dusk that leads to the underworld. They reemerge, immortal, the next morning, in the east. Start the journey anew.

By some trick of Mak-no-ngan, who my I-pugao ancestors say created our earth, we began our new life by flying eastward, against the direction of the gods. We flew from Manila, by the dawn’s early light, and reemerged in Newark, New Jersey, at the twilight’s last gleaming. We remained for two decades in the underworld known as the West. Worry sat in my belly during our flight, hurtling beneath the Sky World’s garden of stars. Were we headed for a new life, or merely a different death?

We were to present ourselves as good immigrants. The kind that would never overstay a tourist visa, then mouth off about it in a book three decades later.

Miles below the belly of our plane, currents of deep, heavy water pulled down on my soft, growing bones. I strained forward in my window seat. I hoped to see the glint of water, or the stars, or the unknown land that lay ahead. I saw nothing. There was only my reflection, cut in two by the double-glass window.

*

I was reluctant to leave Manila, forced to travel in the middle of August in my hand-me-down hot wool dress, a relic from the 1970s. The white ruffled bodice, long sleeves, and high neck itched at my summer-sweaty skin. The shame of being all wrong, a feeling that would become my only lifelong friend in America, reddened my face. My American cousins’ donations were twenty years old, smelling of the mothballs packed in the balikbayan box. The dress was made for winter, an alien concept for my tropical blood.

Prepare a half cup of lemon juice or white vinegar.

“And what will you be doing once you’re in the United States?” said the solemn white man with mud-brown eyes, dirty-blond hair, and a mustache to match. The US Embassy building in Ermita, Manila, was once the residence of the United States High Commissioner to the Philippines, the headquarters of American colonial control. It was built by the US Treasury Department, for our islands were a stream of revenue for America. Next door is where the Spanish had executed José Rizal the century before. He was accused of inciting colonial rebellion through his books, pamphlets, essays, plays, and poetry. Shot to death by firing squad. His dying wish was to face east, towards dawn. The commemorative statue that now stands where he stood faces west, towards the sun, as it sets each day over Manila Bay. Sentenced to gaze upon death forever.

“I wanna go to Disneyland!” I said, my smile blackened by a missing front tooth. Mama had instructed that I was to be agreeable, for once. This was my earliest lesson in how to please the Americans: do not be yourself, do not be contrary, do not be a challenge. We were to present ourselves as good immigrants. The kind that would never overstay a tourist visa, then mouth off about it in a book three decades later.

With a rag dipped into the lemon or vinegar, wipe the sangkalan clean.

Saying goodbye to family at Ninoy Aquino International Airport—another monument for another man shot to death for inciting rebellion—I hid my tears in my Lolo Pedring’s arms. His warm belly muffled my sobs. He promised to visit often. I miss my grandfather’s bedtime stories to this day. I hope that he reads this and sees himself in the way I let a tale unroll itself. The elders do say that we are always accompanied by our most kindred ancestors. Perhaps Lolo is mine.

“OK, time to go,” Mama had said, gently pulling me away, straightening my collar, not-so-gently pounding my upper back. “Stop slouching.” Good posture, cleanliness, and beauty were very important to Mama.

Her excitement at seeing Papa again gleamed from her heavy-lidded brown eyes. He had been away from us for more than two years. My last memory of him was blurred by tears: before walking into the departures door, the same one we were about to enter, Papa had turned around one more time, left hand hoisting his bag over his shoulder, his right hand waving goodbye, his eyes red, brimming with tears. The echo of my voice, lost in the crowd, shouting stay, stay, stay. The gods’ itak slashing down mercilessly, taking away the Papa I knew and loved forever.

Rinse the sangkalan with clean water. Wipe dry with a soft cloth.

Before his soul was cut in two, Papa was a trained architect and virtuoso musician. Like many, he was forced by Marcos’s law to become what Filipinos call an OFW: an Overseas Foreign Worker, required by law to send half of his earnings home, propping up the government’s malfeasance with his own body. He traveled by sea to places with names that meant nothing to me: Philadelphia, Curaçao, Aruba, the Bahamas, Manhattan. He sang and played the piano and guitar with his band. He entertained the ship’s white British and American officers just enough to escape their cruelty, which they reserved for what they deemed to be lesser crew. Papa mistook this for friendship. He would later tell me that those years were some of the best of his life.

“We were in a new place every few days, and we could disembark and go to so many different beaches, visit the towns, see New York City. And the Caribbean! The sand was pink, or white…” He would trail off, disappearing into a different self I would never meet. A self that forgot his wife and two small daughters far away, missing him. A different self, photographed—we would discover decades later—with many women, fingers intertwined, arms around waists, foreheads touching, legs draped over laps on the same beach lounger, or sitting together, T-shirts only, hair rumpled, in a shared bed. A smile that we would rarely see in America.

For Papa, it was better to go to white and pink sand beaches in the Caribbean, strawberry-blond girlfriend in tow, than to our humble, brown-sanded one, the kind that Western tourists never deigned to visit. Better to sing at lunch and supper in cruise ship dining rooms full of pale, wrinkled tourists and adoring female crew members, I suppose, than to lie in bed with his tired, hardworking wife, than to sing to his small daughter, his number-one fan, every night. The Beatles’ “I Will” at bedtime for six years in a row can get a little old, after all.

Take a whetstone, one made of strong mineral from our home soil, and wet it with cool water.

In the years Papa was away, I sleepwalked at night. I went down the stairs in the house on Madasalin Street, where Mama’s family lived. I sleepwalked past the dining room, into the sala. Lolo Baldo, my mother’s father, once found me on one of the sofas, sitting upright, my eyes open and blank. He followed me as I stood up, walked to a window, arms hanging by my sides. Outside, there was nothing and no one that he could see. Lolo Baldo did not wake me. To do so might upset whichever benign engkanto had visited my body, taken me for a walk around the house.

My grandfather sat, tired from a full day’s work, and waited. He told me that each time he found me this way—sometimes in the sala, sometimes in the kitchen—I would eventually shuffle upstairs, back to the bedroom I shared with Mama and my sister. He made sure that I lay back down onto my banig, the floor mat I slept on. I unrolled this woven palm leaf mat each night on the floor next to the raised twin bed, which Mama and my sister shared. We had left our own house, the big marble house, months before, after Papa had boarded the ship in early 1990. After strange men began to watch our windows, circling like stray dogs. After Mama became too afraid to live alone with her two small daughters.

At night, my spirit led flesh through space, searching for a time that would never return. In search of our own kitchen, with its breakfast nook and the stools I sat on every morning. In search of our own dining table with its lazy Susan, all of us within arm’s reach of each other, Papa slicing open the mangoes from our tree as dessert. We would each have a whole mango, Papa crisscrossing each half in the special diagonal way that he knew I loved. In search of our own sala, cavernous and cool on the hottest Manila days, warm and dry during typhoons, long before such storms began to regularly flood the marble house. In search of the tall double doors that opened to our cool back garden, where chickens roamed, clucking among the banana and avocado trees.

In search of Mama, content and sitting, legs tucked into a rattan armchair, flipping through her favorite magazines. In search of Papa playing his piano, or restringing his guitar, telling me to stand far back, just in case one of the strings lashed out. In search of my baby sister, having just learned to walk, toddling on fat legs from one piece of furniture to the next, giggles and drool, wearing only white cotton diapers. My helpful engkanto friend and I must have sleepwalked in search of them, the family that I had lost and would never have again. A future together lost in pursuit of an alternate American reality.

Choose an itak with a sharp edge and a firm grip. Wipe the itak clean. Run its blade through water.

Waiting to board one more flight, I scratched again at my wool dress, which made me stand out from the American children at San Francisco International Airport. They stared at my wilted collar, patent leather black Mary Janes, and bowl-cut hair, recently trimmed by my yaya in the dirty kitchen. I marveled at their translucent skin, flaxen hair, tie-dyed T-shirts, light-up sneakers, and constitutional confidence. It wasn’t just the TV: white people really did look like that. How did they get to be so pale? Does living on this land do that to you? These children ignored their parents, ate Dunkin’ Donuts and Burger King, played Game Boy while we waited. I nibbled at a pack of Sky Flakes from Mama’s handbag, read a komik book of myths Lolo Pedring had given to me a few nights before our flight to America.

“The Greek myths I read to you? They are very good, but look at these,” Lolo had said.

He had feigned nonchalance, handing me three thin books. The books were stapled at the spine and, unlike the colorful Marvel and Archie Digest comic books Papa sent me, these komiks were in black and white ink on pulpy newsprint, which smeared ink on my fingers. The cover bore intricate drawings of gods, aswang, engkanto, dwende, and sirena, beautiful against the backdrop of a giant balete tree.

Clutching the thin book of komiks from my grandfather, I stepped off the airplane at Newark, my spirit cut into two, forever.

“You should know these stories too. If you like them, I can send more.”

Lolo Pedring had watched while I riffled through the pages, sat down to read the first one. A small, satisfied smile had creased the corner of his mouth. I remembered him as I sat there, unaware of San Francisco, just outside. I looked up at the airport gate that led further into the West, further into the underworld. Would Lolo be asleep by now? I had wondered. Would he, too, be wishing he could tell me a story from memory, as he often did?

*

In the myth of the divided child, the goddess Bugan descends from the highest realm of Sky World to join her beloved, a mortal man. At a hut near his village, they begin a family of their own. She bears him a son, and for a time, they are happy. But not long after, Bugan is made to feel unwelcome by the villagers. They fear her power, envy her beauty. They poison her garden so that she cannot eat. Their sharp words are knives at her back. Sad and lonely, Bugan decides to take her mortal husband and half-godly children back to Sky World. But her husband is afraid and refuses to go. Bugan makes a fateful choice: she tears their son in two, keeping the boy’s lower half for herself, the upper half for her husband.

“This half, with the heart, will be easier to raise on this earth,” Bugan tells him. She ascends home with her half.

Weeks later, a stench reaches the highest level of Sky World, where Bugan and her son live. Terrified, she rushes down to earth.

“What have you done?” she asks her mortal husband. Unaccustomed to caring for a child, he had neglected their son. The boy died not long after Bugan’s departure.

In rage, Bugan tears the dead body into pieces with her bare hands, needing neither itak nor sangkalan to do so. Her grief brings her to the edge of the forest, where she throws the pieces away. An ear lands on soil, turns into the first mushroom. An arm transforms into the first snake. The boy’s skin, I-pugao dark and brown, becomes a winged creature, that which we now call the kukuk bird. In fury and despair, we conjure great and startling things.

With even, long strokes, run the itak’s blade, wet with water, across the stone. Repeat along the length of the blade until sharp, catching on the skin-edge of a finger.

On that flight to America, I listened to one song, louder than my little sister’s cries for more milk. I had discovered it on the flight from San Francisco to Newark, blaring through the airplane’s free headphones. I did not know what the piece was called, but I knew how to find it through my seat’s menu buttons. I had a favorite section. Two-thirds of the way through, a piano in adagio gave way to a blossoming string orchestra. It ushered in a feeling of optimistic wonder, a brief comfort on a journey I didn’t want to take. The floating strings were legato and unhurried, dropping down to create space. I snuggled into the window and watched the clouds pass beneath me—at dusk, over the Pacific as we flew over Taipei, then again at dawn, as we approached California. The rhapsody peaked to a dreamlike crescendo. I imagined that I was a goddess from Sky World, discovering new lands. How lucky the United States was to be heralding my arrival. Bugan, disguised in a hot, itchy-as-hell wool dress smelling of mothballs. But unlike Bugan, my family would be back together again.

That dreamy, violin-ribboned, trombone-draped passage—Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, I would discover years later—was brief. It lasted for less than three minutes. Played on repeat, it felt like the forever I had wanted for my sister, my parents, and me. When we touched down in America, the song ended, cut off halfway by the pilot’s announcement. The flight attendant collected our blankets. With a gentle hand, she took back my free headphones while I jabbed at the control panel. Please, just one more play of the song.

The itak is now ready for use. Rinse once more, under running water, to remove any small, sharp metal shavings.

Clutching the thin book of komiks from my grandfather, I stepped off the airplane at Newark, my spirit cut into two, forever.

__________________________________

From Dirty Kitchen: A Memoir of Food and Family by Jill Damatac. Copyright © 2025. Available from Atria/One Signal Publishers, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.

Jill Damatac

Jill Damatac is a writer and filmmaker born in the Philippines, raised in the US, and now a UK citizen, she lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. Her film and photography work has been featured on the BBC and in Time, and at film festivals worldwide; her short documentary film Blood and Ink (Dugo at Tinta), about the Indigenous Filipino tattooist Apo Whang Od, was an official selection at the Academy Award–qualifying DOC NYC and won Best Documentary at Ireland’s Kerry Film Festival. Jill holds an MSt in Creative Writing from the University of Cambridge and an MA in Documentary Film from the University of the Arts London. Follow her on Instagram @JillDamatac.