A Most Rare Compendium:

An 18th-Century Guide to Magical Treasure Hunting?

Hereward Tilton on the Strangest of Manuscripts

We do not know who owned the manuscript before 1928, when A Most Rare Compendium was sold to the Wellcome Library by the Viennese antiquarian bookseller V. A. Heck for 1,200 Swiss francs (48 pounds sterling). Heck’s sales announcement describes it as an “exceedingly curious” and “artfully illustrated Höllenzwang manuscript” that “undoubtedly” originated in Austria circa 1760, and that concerns “the conjuring of spirits, chiefly for the purpose of treasure-hunting.”

While the orthography of A Most Rare Compendium suggests that it is indeed Austrian, Heck’s description is problematic for a variety of reasons.

First, the Compendium was created at a somewhat later date than that proposed by Heck, or indeed by Samuel Moorat, who suggested “circa 1775” in his catalogue of Wellcome Library manuscripts. The psychedelic ruminations that open the main text of the work are derived from the Catholic theosopher Karl von Eckartshausen, who in his Aufschlüsse zur Magie (Disclosures on the Subject of Magic, 1788–92) bemoans the flashbacks caused by his careless experimentation with the art of psychedelic fumigation.

Likewise, the closing passage of our manuscript allegorizing the popular topos of the veiled statue of Isis is derived from the final volume of Aufschlüsse zur Magie, and the date of this volume’s first publication—1792—provides a terminus post quemfor the composition of A Most Rare Compendium.

Second, A Most Rare Compendium is not only “most rare”—it is unique, as its creators knew full well. Our manuscript did not evolve from an earlier relative, a fact that is highly unusual for the magician’s manuals now popularly known as “grimoires.” While Heck interpreted the Compendium as a “difficult-to-access” grimoire akin to the medieval Clavicula Salomonis (Key of Solomon), such manuals are typically compilations of textual fragments drawn from related (and similarly fragmentary) compilations.

By contrast, our manuscript is a one-off work of artifice derived principally from printed sources that its creators had to hand; for instance, its extracts from the Arbatel, Ars notoria, Trithemius’s Liber octo quaestionum and Agrippa’s De occulta philosophia are all drawn from the first volume of Zetzner’s 1630 edition of Agrippa’s Opera. Indeed, the very title of A Most Rare Compendium suggests its creators were trading on its (absolute) rarity, which constitutes something of the work’s raison d’être.

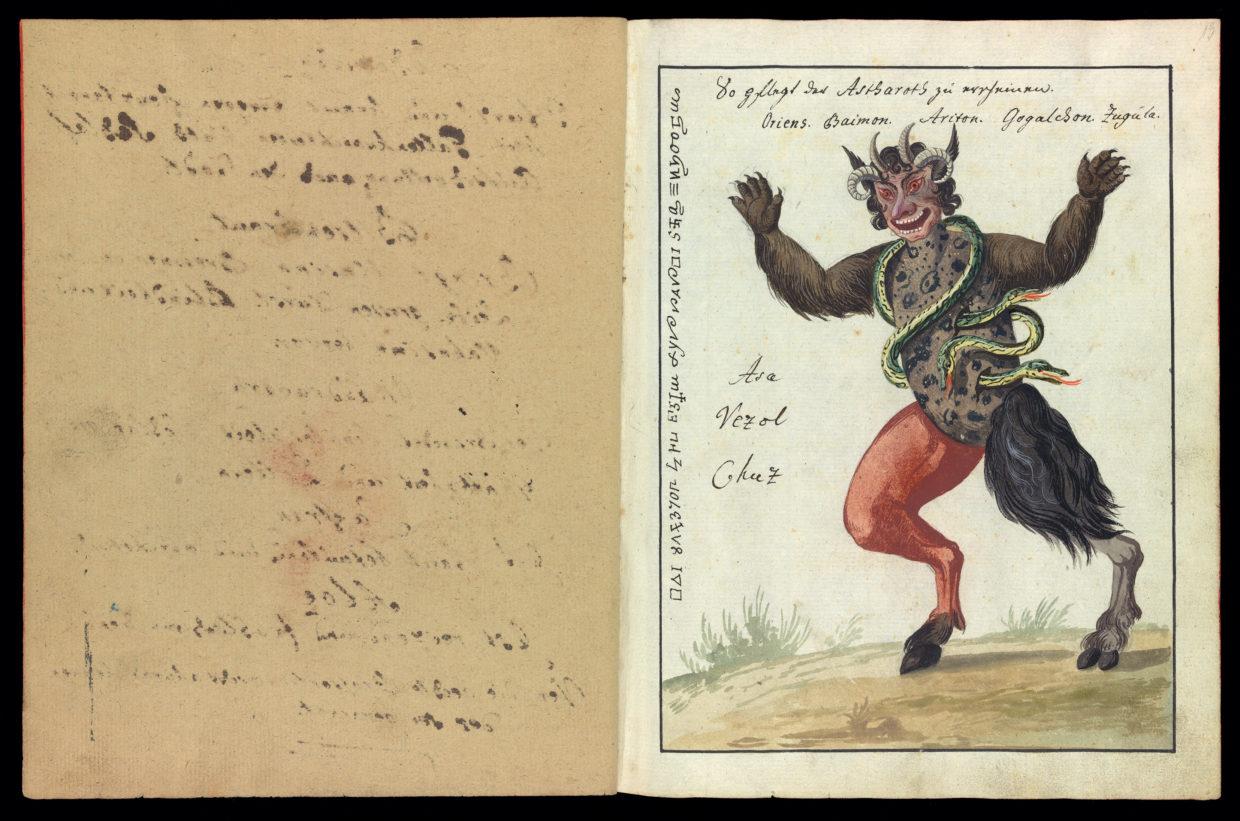

Third, as an early modern German expression of the Solomonic demon-binding tradition, the Höllenzwang (“coercion of hell”) family of grimoires is principally associated with the name of Johann Georg Faust (c.1480–1540/1), Renaissance Germany’s self-styled “fount of necromancy,” and with the coercion of diabolical powers for the purpose of obtaining the treasures they guard. Yet our manuscript claims to be a “compendium”—an epitome or abstract—of writings on nigromancy, meaning black magic in general; the theme of magical treasure-hunting is referred to explicitly in only three of the compendium’s thirty-five illustrations and three times in the text.

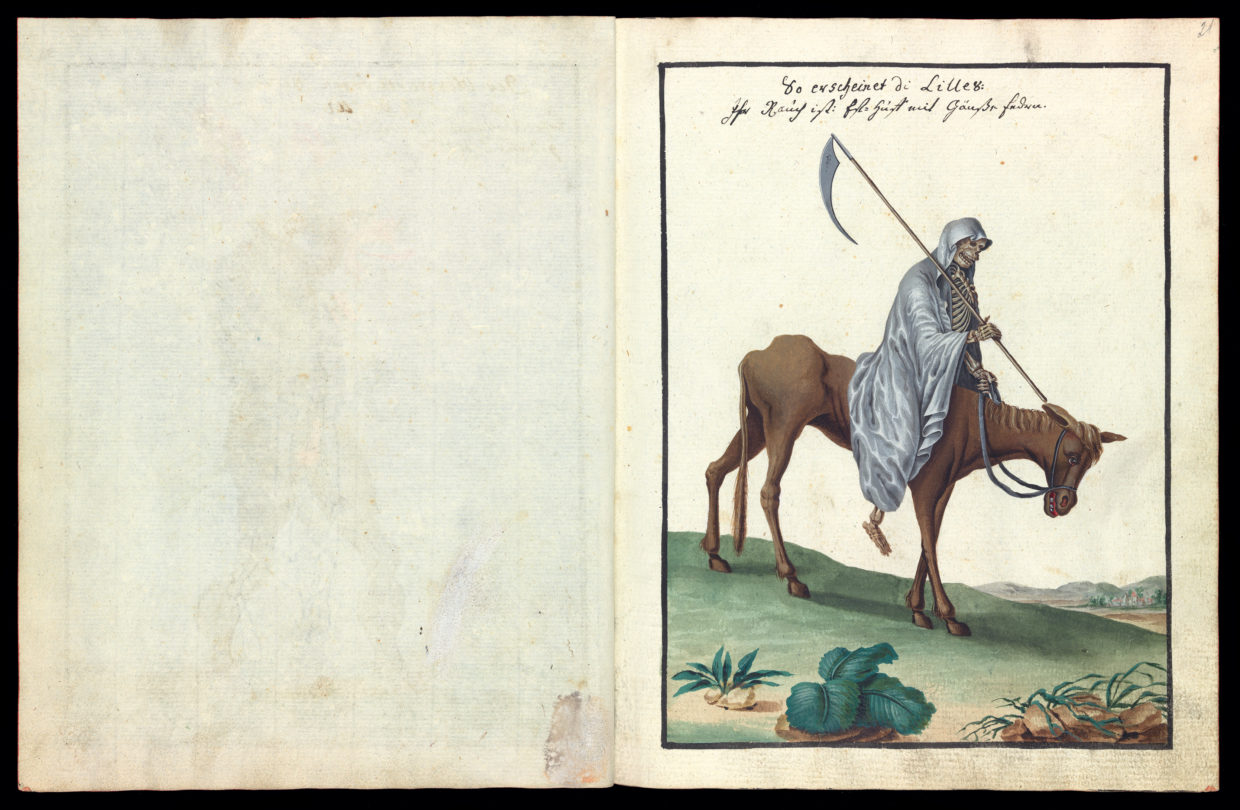

Besides generic methods for summoning demons—invocations, sigillary body painting, circle-casting, etc.—the text and illustrations of A Most Rare Compendium allude specifically to necromancy—described here as the art of summoning the dead, or of using corpses for various magical ends—and catoptromancy—described as the art of scrying with magic mirrors to communicate with the absent or dead, or to obtain sought-after objects.

While these arts and methods are certainly of use in magical treasure quests, none of the print or manuscript sources of A Most Rare Compendium bears any clear first-hand relation to the Höllenzwang literature; for instance, the names and hierarchies of its demons are drawn chiefly from The Book of the Sacred Magic of Abramelin. Furthermore, when it comes to discussion of the diabolical pact, rather than reproducing the famed pact of Faust—such as we find it in certain Höllenzwang manuscripts—the opinions of the notorious witch-hunter Martín del Río are given alongside those of the Arbatel.

Nevertheless, that V. A. Heck saw the Compendium as a Höllenzwang grimoire is telling, as the Höllenzwang textual family constitutes not only an important part of our manuscript’s cultural context, but also its core conceptual inspiration. This conclusion is confirmed, first and foremost, by the compendium’s juxtaposition of psychedelic drug use with the perils of magical treasure-hunting and the diabolical pact; as we shall see, this confluence of themes points not only to the Höllenzwang grimoires but also to the occasionally tragic history of their employment in the magical quest for treasure.

The apparitions sent to distract magicians and lure them from their protective circles are gleefully depicted in A Most Rare Compendium.

Furthermore, magical treasure-hunting was a “fashionable crime” running at epidemic levels in 18th-century Austria. The expectation that one would use the various nigromantic techniques detailed in A Most Rare Compendium for treasure-hunting purposes is clearly reflected in its remarks on the diabolical pact: those who have been rescued from the clutches of Satan by white magicians or priests are admonished to donate their ill-gotten hoard to the Church and the poor.

*

The folk beliefs that lend this particular strain of demonic magic its regional color have pre-Christian origins. The pagan Germanic notion of vast subterranean treasures guarded by dragons persisted in medieval and early modern Christendom, as did the belief that such hoards could be gained by magically subduing their guardians. Appearing not only as dragons but also as snakes, black dogs and spectral maidens, in the Christian popular imagination these treasure guardians were interpreted as guises of the Devil, who might be invoked and bound in the manner of an exorcism.

Taking place at lonely, liminal locations—gallows, graveyards, ruined castles and churches—the binding operation was believed to be exceedingly dangerous, as the Devil would do his utmost to divert the treasure-hunter from the correct procedure.

The apparitions sent to distract magicians and lure them from their protective circles are gleefully depicted in A Most Rare Compendium, as are the dire consequences of failing to follow the prescribed procedure: a cock-headed, dolichophallic demon, extinguishing a lantern with its urine, drags an ill-fated treasure-hunter to his doom. Apparently dissatisfied with the illustrator’s original dating of this ghastly event to 1768, a second hand has altered that year to 1668—perhaps feeling that the original date betrayed the manuscript’s relatively late composition, although neither year sits well with the title page’s 1057.

While a number of errors—failing to maintain silence, for example, or turning around at a noise—might have caused the disaster shown here, the lack of a protective circle is conspicuous. The illustration is set in contrast with the preceding portrayal of a correctly performed treasure-hunting operation, here involving ritual nudity and the necromantic manipulation of a reeking corpse at the gallows. In both images the most sought-after (but by no means essential) component of the magical operation is depicted: a literate magician, who has brought a grimoire with the requisite demonic sigils and invocations to the conjuring site.

*

With its carefully inked sigils and numinous incantations, A Most Rare Compendium lends its readers the impression of being just such a grimoire. But was it designed for a practical purpose such as magical treasure-hunting?

As a dedicated genre of treasure-hunting literature, the Höllenzwang grimoires emerged in 17th-century Germany as descendants of the Clavicula Salomonis (Key of Solomon), which included invocations for treasure-hunting and was widely used for that purpose. The regional, specifically Germanic inspiration of the earliest Höllenzwang framing narratives is a tale related by the first printed Faustbuch of Spies (1587), in which Mephistopheles reveals to Faust a gleaming treasure guarded by a “ghastly great dragon” within a ruined chapel; banning the guardian, Faust attains its hoard.

Elaborating on this story with further folktales of magical treasures and their diabolical guardians, Widmann’s second Faustbuch fed a growing appetite within German popular consciousness for demonic encounters and magical treasure-hunting in the wakeof the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48). In the course of that conflict, marauding sectarian armies had been unable to hold territory, and thus the treasures they looted—above all from Catholic churches—were buried in the often vain hope of later retrieval.

Amidst a harsh post-war economic climate, the Höllenzwang grimoires offered a quick magical solution to financial hardship, and from its epicenter in the German states—where it had become the most commonly prosecuted form of magic by the turn of the 18th century—the treasure-hunting craze spread to Austria, Switzerland and Bohemia.

When attempting to situate A Most Rare Compendium in relation to the Höllenzwang texts, it is necessary to distinguish between earlier operative Höllenzwang manuscripts and elaborate later derivatives created for the libraries of curious Enlightened gentlemen. A good example of the former class is held at the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek in Weimar: the Nigro-Mandia Capala Nigra alba d’Johannes Faust, which stems from the principality of Anhalt in the decades following the Thirty Years’ War. Scribbled down with alternating ink-colors in a cheap notebook, the Nigro-Mandia commences with a core textual unit of the Höllenzwang grimoires: some short words of advice concerning the operation and its astrologically appropriate days and hours, followed by a sevenfold summoning, binding and release of Aziel, a spirit guardian of buried treasure and goods.

Within the template-like invocations we find the operator bluntly demanding the immediate delivery of 8,000 guilders (another version of the core text specifies looted Catholic liturgical artifacts). Amidst unique cacographical Machtworten (words of power) there are imprecations to Mary, the Evangelists and the archangels, as well as invocations with generic Judeo-Christian divine names (Tetragrammaton, Soter, Emanuel, Elohim, etc.) reminiscent of the Clavicula Salomonis and any number of medieval magical sources. The practical nature of the manuscript is underscored by its ruled appendix, which supplies the reader with the likely locations of buried treasure within Anhalt; a fumigation recipe and a few sentences extolling the apotropaic virtues of vervain have also been added.

Among the passages of A Most Rare Compendium that are derived from manuscript sources, the strings of Jewish divine and angelic names in two related demonic invocations are strongly suggestive of a relationship to the Clavicula Salomonis. Nevertheless, in early Höllenzwang texts such invocations are lengthy and repetitive, and are often supplemented with extensive lists of verba ignota stemming from the Ars notoria. Their practical purpose is trance induction rather than the entertainment of a casual reader.

Another passage of the Compendium derived from an as-yet-unidentified manuscript source concerns the “cacomagical” or black-magical mirror; its use to communicate with the dead is referenced in the illustration of catoptromancy, while certain necromantic elements of its construction—a burial under gallows, black hair, a hanged man—are alluded to in the first illustration of treasure-hunting. Although the text indicates that this mirror may be used for treasure-hunting, the artifact is unrelated to the dedicated treasure-hunting “earth mirrors” of the Höllenzwang literature, and appears instead to be a distant relative of the mirror of Lilith described in the so-called Munich necromancer’s manual.

The creators of A Most Rare Compendium simultaneously reflected and appealed to prominent motifs in the contemporary cultural memory of magic.

While there is no clear textual relationship between the Höllenzwang family of texts and A Most Rare Compendium, conceptually our manuscript’s closest relative is the late compilation of Faustian Höllenzwang texts entitled Magia naturalis et innaturalis held by the Landesbibliothek Coburg. Like the Compendium, it dates to the late 18th century, and the text has been adorned with a plethora of imaginative watercolor illustrations of demons and their sigils. Among them, the representation of Aziel as a bull with fiery eyes and phallus is particularly noteworthy although the aggressively explicit depiction of humanoid genitalia is a unique feature of A Most Rare Compendium.

Coburg’s Magia naturalis et innaturalis is exemplary of the aforementioned second class of Höllenzwang manuscripts: it is not a practical treasure-hunting text, although it has been created to resemble one. The purposeful antiquation of materials and style is a feature of certain manuscripts of this sort, such as the Praxis magica Faustiana held at the Herzogin Anna Amalia Bibliothek.

Bearing the date 1527, it is written on parchment in 16th-century German chancery script, and is decorated with various transgressive emblems: Faust whips a chained goat, rampant lions lick a mandrake root, and a rooster gazes dozily at a diabolical sigil with the words “Lucifer amicus meus dilectus et servus.” Apart from an exploitative willingness to titillate, Höllenzwang manuscripts of this second class share a particularly important feature with A Most Rare Compendium: those who could afford them would have had little need for magical treasure-hunting.

*

Compiling and illustrating diverse textual fragments, the creators of A Most Rare Compendium simultaneously reflected and appealed to prominent motifs in the contemporary cultural memory of magic. Among those motifs we find the magical employment of psychoactive substances to access the spirit realms, a practice that—beyond the domain of witchcraft—is primarily associated with treasure-hunting in 18th-century folk magic. Again, the Höllenzwang grimoires and the history of their practical employment provide the most relevant comparisons.

The extracts from von Eckartshausen’s Aufschlüsse zur Magieoffer an extensive list of ingredients for entheogenic potions, salves, and above all fumigations designed to “poison the imagination” and transport the magician into the realms of dreams and madness. While some of the listed psychedelics—the ancient entheogen saffron and the rare, exotic aloes wood—remain exceedingly expensive to this day, one is found throughout the European countryside, and has now established itself worldwide as an invasive species: the common reed (Phragmites australis).

A Most Rare Compendium specifies usage of the plant’s root or rhizome, which was recently discovered to be an indigenous European source of dimethyltryptamine (DMT). This profound psychedelic compound requires the addition of monoamine oxidase inhibitors—such as those present in the Amazonian ayahuasca vine (Banisteriopsis caapi) or Syrian rue (Peganum harmala)—to infiltrate the brain via oral ingestion, and hence the psychoactive properties of the common reed go unmentioned in medieval and early modern herbals.

Nevertheless, the dried rhizome might be effectively employed as an ingredient in a psychedelic fumigation. In our manuscript a censer for such fumigations is pictured next to the Solomonic sword within the magician’s circle; the reader is also warned of the dire consequences of overdosage.

Most of the simple drugs listed herein are psychoactive nightshades: mandrake, hemlock and henbane are specified, although this family also includes belladonna and datura. We find nightshades compounded with opium not only in the so-called witches’ ointments and related medieval anaesthetics, but also in the fumigations of the Höllenzwang literature—Herpentil’s Liber spirituum potentissimorum, for example, recommends a mixture of opium and henbane. However, the hallucinations produced by the tropane alkaloids of the nightshades are a symptom of anticholinergic syndrome, and overdosage—be it via topical, oral or inhaled administration—may prove fatal.

Determining the correct dosage is particularly difficult when working with fumigations: thus Herpentil recommends a lonely forest or meadow as an ideal location for the operation, and if a building is to be used, a door or window must be kept open.

The consequences of failing to follow this good advice are evident in the so-called “Jena Christmas Eve tragedy,” a famed case of magical treasure-hunting gone wrong that persisted in public consciousness throughout the 18th century, and that served as a test case for the relative merits of reason and biblical revelation as explanatory principles in an Enlightened age.

The most bewitching ingredients of A Most Rare Compendium are, of course, its watercolor illustrations.

In 1715 a spectral maiden in white appeared to the owner of a vineyard in the hills near Jena, leading him to believe a treasure trove from the Thirty Years’ War lay close by; according to his testimony, she caressed him seductively, telling him to seek the Springwurzel (spring-root). Associated with mandrake and the herbs of the garden of Hecate, the spring-root was thought to possess the power of opening locked treasure chests and vaults. Two illiterate farmers were enlisted to procure this mysterious plant, and on Christmas Eve they met in a lonely hut on the vineyard with a medical student, who had been recruited to bring (and read) his manuscripts of the Clavicula Salomonis and “Faust’s Höllenzwang.”

Alas, due to the cold of midwinter the door and windows were kept firmly shut, and their attempts to summon the vexatious treasure guardian by way of psychedelic fumigation left two of the three men dead. Worse still, a guard dispatched to watch over their corpses suffered the same horrendous, hallucination-filled fate after the makeshift censer—a charcoal-filled flowerpot—was innocently reignited.

While prominent theologians and physicians debated whether the Devil or carbon monoxide were to blame, one little-known writer mustered an impressive array of authorities on magical entheogen use—Agrippa, Paracelsus, Gödelmann, van Helmont, Borel and Bekker among them—to support his thesis that vegetabiles narcotico-phantastici had been employed, and that the prime suspect was henbane.

*

The most bewitching ingredients of A Most Rare Compendium are, of course, its watercolor illustrations. Given the prominence of the manuscript’s passage on entheogens, the suspicion naturally arises that the artist was psychedelically inspired. While this possibility cannot be ruled out, it should be noted that these illustrations also incorporate standard motifs from the medieval and Reformation representation of the diabolical realms: consider, for example, the similarities of the guardian of purgatory with Matthias Gerung’s well-known satire on the Catholic priesthood, or those of our manuscript’s centerpiece—the demon Dagol—with depictions of the Devil in the Florentine tradition.

The undeniably arresting images of the Compendium have been executed by a trained and modestly talented artist, who has drawn upon Großschedel’s Calendarium naturale magicum perpetuum—as well as his or her own imagination—in the design of the demonic sigils. Accompanying the image of Astaroth we also find a faux-cipher inscription suggestive of the illustrator’s acquaintance with the cipher alphabets of Trithemius, presumably via Agrippa. Although the evidence is by no means conclusive, these purely imaginative elements feed a suspicion that the artist is a second party contracted to illustrate passages compiled by an individual moderately more conversant with the dark arts.

Although it has undoubtedly inspired readers down through the years to experiment with the archaic techniques it describes, A Most Rare Compendium is not a practical Höllenzwang manuscript of the sort one might pore over with farmers in the local tavern or furtively transport to a lonely vineyard hut, flowerpot and entheogens in hand. If it can indeed be considered a grimoire in the Höllenzwang tradition, then it is also a work of supernatural horror composed in the form of a Höllenzwang grimoire, and its decidedly Gothic aesthetic confirms a date of composition in the dying years of the 18th century.

While this demystifying reading might bleed some of the transgressive thrill from the words “Touch me not,” it in no way detracts from our manuscript’s value as a highly entertaining conveyor—and unique reinterpretation—of Germanic magical tradition.

__________________________________

From Touch Me Not: A Most Rare Compendium of the Whole Magical Art. Used with the permission of the publisher, Fulgur Press. Introduction copyright © 2019 by Hereward Tilton.

Hereward Tilton

Dr. Hereward Tilton is a lecturer in Reformation history and early modern esotericism at the University of Exeter in England. He holds degrees in the history of European esotericism and the psychology of religion, and he has published work on Rosicrucianism, alchemy and magic, most notably his book The Quest for the Phoenix: Spiritual Alchemy and Rosicrucianism in the Work of Count Michael Maier (1569-1622).