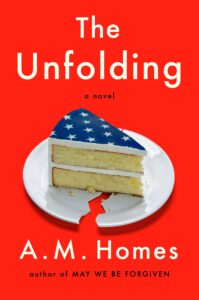

A.M. Homes on Being—For Better or Worse—“a Very American Writer”

The Author of The Unfolding in Conversation with Phil Klay

Photo by Marie Sanford.

How many of us writers, gazing upon the spectacle of recent American politics, have despairingly called to mind Roth’s infamous comment about the difficulty of making American reality credible? Even in the 60s, Roth thought it so extreme “it stupefies, it sickens, it infuriates, and finally it is even a kind of embarrassment to one’s own meager imagination.” By 2022, how much harder is it for the realist to make reality plausible, or for the satirist to exaggerate and caricature? Our former president once suggested we use nuclear weapons against hurricanes, for God’s sake.

And yet, for the same reason, we desperately need good political fiction—novels that allow us to step outside our frenetic political culture and attempt to understand what is happening to us. This is the task A.M. Homes achieves with The Unfolding. The novel doesn’t simply tour the funhouse mirrors of contemporary politics so much as situate them within the personal and domestic spheres, where characters with grotesque but submerged ideological assumptions take one seemingly rational step after another as they create our new, horrifying normal. It’s funny, it’s dark, and it’s incredibly incisive.

I met A.M. when I began teaching at the writing program at Princeton, and she took it upon herself to show me around. I’d already known and admired her for her work—in personal she was warm, generous with her time, ready to laugh, and relentlessly curious about everything, especially the human particulars behind grand policies.

I remember one lunch we shared with an economist who’d been in and out of government where the conversation moved between economic policies and trends in the second half of the twentieth century to the intimate life of the Reagans in his twilight years. So it’s fair to say that before I even cracked the first page of her new novel, I already knew it was going to be good.

–Phil Klay

*

Phil Klay: You’ve written an astounding, and very funny, novel about a group of men, horrified by the Obama election, who feel the country is being stolen from them and try to conspire to take back the country. And you started this long before Trump. What did it feel like, writing this book as your nightmares become our reality? And how did that effect the writing?

A.M. Homes: I started The Unfolding before Trump was even a candidate. I had the gnawing sense that the U.S. political establishment had lost touch with the average American. Politics were no longer about representing the people but rather the interests of the politicians. That realization dovetailed with the sharp rise of dark money flowing into our political process.

When I first had the idea—my editor said, “But you don’t write science fiction.” And then when Trump won the election they called and asked “Where is it?”

I’m drawn to characters who are very different from myself. As a writer, and in my own life, I want to understand people whose experience and point of view are other than my own whatever it might be.

Trump’s election was terrifying—because it confirmed that what the men in my book were talking about was not science fiction. Suddenly, much of what I was writing was becoming closer to the truth—which was unnerving. The last thing a catastrophic thinker wants is to be right. I wanted to stay on edge of the absurd and the surreal even as reality kept getting weirder and weirder.

PK: I’m fascinated by the approach you took to these characters. They’re powerful political actors, people we’re accustomed to thinking of in terms of the monstrousness of how they wield their power, but who here come across in all their absurdity, humanity, and blindness. Why did you want to spend your novel among these characters?

AMH: I’m drawn to characters who are very different from myself. As a writer, and in my own life, I want to understand people whose experience and point of view are other than my own whatever it might be. That combined with my desire to unpack what was going on in this country made it useful to spend time with these men and this particular family.

For me each character is an individual and we are all flawed. I don’t think about characters as good or evil or whether or not I like them. Ultimately, I am always writing about human behavior, what compels someone to act the way they do, what drives their perceptions and needs.

The novel is a braid of a large scale social/political novel and an intimate/domestic story about a family. A major thread is the coming to consciousness story of a mother and daughter, a multi-generational view of the female experience. Importantly, the Big Guy, also begins to understand more about the impact he’s had on the women in his life.

PK: Though this is a political novel, it isn’t a novel with extensive arguments about ideology. Rather, many of the characters don’t argue their ideology so much as assume it, and act accordingly. But there’s also Meghan, a young person undergoing her own kind of awakening. When she casts her first vote, for McCain, she says feels like she’s in Shirley Jackson’s The Lottery. And her re-evaluation of herself and her politics seems as much about deeply personal relationships as it is about ideology. Why did you take this approach?

AMH: For me it always comes back to the characters and inhabiting the story from the inside out—organically. When we first meet Meghan, she is naive, a kid who has grown up in a bubble, with great privilege and protection from reality. As she comes into her own, she goes through a period of waking up which is something we all do as we prepare to separate from our families and move into the larger world.

This is a time when many of us look at the family narrative—the story we were told (or sold) about who we are and what we believe. Meghan begins to realize there’s an enormous amount she doesn’t know, an enormous amount she’s taken for granted and that despite being told that women can do whatever they want—it’s also not true. Her awakening is also the beginning of her empowerment— the opportunity to set her own course and to give the rest of us hope for a better future.

PK: This is a dark comedy, and the humor, in my reading of the book, plays an extremely serious role. The comic approach, highlighting the clownishness in a group of people who have taken it upon themselves to determine the fate of the country, seems not just a way of delivering pleasure to the reader (and I got a lot of pleasure out of this book), but also as a way of seeing clearly and truthfully. So I wanted to ask about how you thought about humor in this kind of writing.

AMH: Comedy is serious. It allows us to break the surface tension and to dig deeper into subjects that are painful, taboo or otherwise difficult for people to otherwise talk about. Laughter creates space and I needed room to explore these really difficult social and political questions without seeming to be hammering too hard on the big questions and big ideas.

PK: This novel shows events of moral importance, and political importance, but the hand of the novelist is light. You have characters with very different politics from your own grappling with moral and political and personal questions, and you take us inside the thought process without neatly providing us an authoritative stance on the questions about history, politics, and morality that the characters grapple with. Did that take restraint? Did it feel like a risk?

AMH: Unless explicitly writing non-fiction, I am not present in my books. That said there is a thread in this one—adoption—that echo’s something in my own life but in a very different way. My goal is always to write what is true for the character. What has their life been like? What has already happened? What events shaped their POV, their narrative? So, I would say that it didn’t take restraint but rather a commitment to representing the points of view that were organic to the characters. Is it a risk? Always, and no doubt with this book being political some on both sides will think I failed. But I feel pretty comfortable that I understand who is on the page and why they are there.

PK: So, there’s outlandish stuff in here, though I suspect the more outlandish, the more it aligns with the actual historical record. How do you think about blending fact and fiction?

AMH: I learned a lot about history while writing this book—for example I didn’t know George Washington had been a disgruntled British Soldier and complained re lack of fair pay before he became “our” George Washington. I think the book is not so much a blend of fact and fiction as it is fiction supported by fact. I wanted to write a book with deep historical references and importantly I wanted to use history, facts, specific names, details to illustrate the evolution of the political and social process from the end of WWII and the Eisenhower administration until now. Eisenhower’s famous last speech, a warning about the “rise of the military industrial complex,” is key to understanding the US economy, politics and the military from that moment until today.

I wanted to write a book which talked about historical moments that some people may not be aware of; I’m increasingly conscious of the fact that we live in a time when there are numerous histories and I just wanted to ration a version of history. And what I discovered as I was writing this was really my affection for both history and fact, and I wanted the story to read as real/plausible in the sense that I do believe that there are real people very much like my characters who walk among us and exert a lot of influence on our lives.

PK: Our relationship to history looms large in the novel. The Big Guy was born on VJ Day, and feels this makes him the archetypal American. The mythology of WWII and America’s role to hegemon clearly underlie his assumptions about the world that is dying. Meanwhile his daughter is reassessing American history, told to her as patriotic fables, and considering more seriously the role of the revolutionary. I’m curious, is writing a novel like this a patriotic act? A revolutionary one? Where do you see yourself, as a novelist, and the writer’s place in American political life?

AMH: I see myself as a very American writer for better or worse. Growing up in Washington, D.C. was certainly a formative experience with regard to bearing witness to society and culture on both a large/national scale and a smaller/domestic scale. I’ve always explored the spaces between the public and private self.

The writer Grace Paley would often be asked if a writer had some great moral obligation to society and she would say the writer has the same obligation as a plumber—which is just to do their job as well as possible. I do think writers have an obligation to bear witness and I always want to create work which is both entertaining but also provokes people to think, to ask questions of themselves and those around them. Who are we to each other, what are our responsibilities? I don’t presume to have answers but I want to have the conversation.

PK: Alongside history, there are memes, slogans, political spin. “You want to spread ideas like a virus,” one character says. And sometimes, you get the sense the characters are spinning themselves. “This isn’t about money; it’s about power,” the Big Guy says at one point. But when his co-conspirators recoil, he revises his argument: “This isn’t about money,” the Big Guy says, “it’s about freedom.” Where does ideology end and strategic rhetoric begin? And do your characters even know?

AMH: There is a character in the book, Twitch Metzger, a former advertising executive who begins to teach the Forever Men about the use of language as a tool for selling ideas, for shaping opinion. He also talks about the power of data algorithms that function invisibly and very effectively to both feed us ideas or information (and sell us products) and I am in general worried that we as a society are less aware of how powerful those tools are. Bending truth or fact and language to suit one’s purposes is deeply dangerous and is not new to history.

All of history is a story and the question is what are the stories we tell ourselves, what are the stories we use to comfort, to motivate, to agitate, and who controls the narrative? These questions and the failure of history as subject to incorporate the fullness of histories in its stories to my mind makes art of all types all the more important because it serves as document, illustration and interpretation of the time in which it was created.

PK: The Capitol is in your blood, literally, in fact. How did growing up in DC effect your approach to writing political fiction?

AMH: The Unfolding is absolutely my Washington novel even though it is set all over the country. Growing up in DC was formative in so many ways. My family were far left leaning, always marching for one reason or another. Starting in high school I worked on anti-nuclear marches and indigenous American rights marches; funny enough my expertise as a teenager was security—I think because I was such a catastrophic thinker. I worked with organizers who would come in from around the country—with names like Wave and Crash.

We would organize meetings with the DC police and the Capitol Police and The Park Police because all three had some jurisdiction and they would ask how many marchers do you expect? 300,000 I would say. And they’d say ok well we can give you 100 rolls of snow fence (that’s the fence with tiny wooden pickets and wire that’s most often used to stem beach erosion) but it was the only fencing allowed on federal and park property. And then they would say—you can give us 10 names for the bathroom in the US capitol—and I’d write down, Jerry Brown, Jane Fonda, Joni Mitchell, ME, and so on.

I had the experience of for many years thinking of Washington as a kind of dysfunctional small southern town with great tension and divides around race, economics and equity. The summer that Nixon resigned I was at camp in North Carolina, people around me were sobbing and saying that their mamas were going to have heart attacks while at the same time I was thinking—there must be a party happening in Georgetown. It was then that I began to realize that Washington was the capital of the country. That was fascinating because the dysfunction has been clear to me for years I also was witness to as a kid having schoolmates that changed every four years and then as think tanks and lobbying and other options became viable, families who moved to Washington stayed in Washington and that community that serves bureaucratic bloat grew and grew.

PK: This strikes me as an optimistic book. It surveys American life, sees a lot of sickness in the corridors of power, but I found myself moved by it, and by the trajectory of Meghan, who is not captured by the same myopia as her father, and whose world seems bigger, and more dynamic, because she is opening herself to more of it. Do you share that optimism?

AMH: Meghan is a key figure in The Unfolding. Her coming to consciousness, realizing that not only might she see the world differently from her parents, but recognizing the responsibility that comes with privilege and the idea that her future is something she must create, inhabit and own for herself is enormous. Meghan is our hope, she represents the awakening to the idea that each individual can make history both on small scale—within their family and community and on a large scale within a country and a globe. We must relearn how to talk to each other, how to argue and disagree nonviolently. To sit silently is to surrender.

PK: You’ve mentioned to me that you were told there weren’t a lot of women writing this kind of large, expansive, ambitious take on American life and politics. Why do you think that is?

AMH: Women’s fiction is not valued in the same way as books written by men. Grace Paley used to say women have always done men the favor of reading their work, but men have not returned that favor. We know that is true from statistical studies of who buys books and often I meet men who say they don’t read books by women. They declare it almost as a kind of allergic reaction or expression of fear or disdain. But I’ve never met a woman who says she doesn’t read books by men.

And then let’s drill a little deeper and remember that for many years women did not have a seat at the table. In the early 20th century the majority of women did not work outside the home and those that did were young and unmarried—in part due to cultural norms, the kinds of work available, and legal constraints. Women didn’t have the same access to education. That didn’t really change until World War II when women went to work filling jobs left empty by men who went to war. And post WWII more women stayed in the workforce but continue even now to be paid less than men doing the same work.

And some fields—economics for example where women represent only 1/3 of PhD students—a number that has not changed in 20 years. In the world of publishing, a gentleman’s profession, the jobs for women were often clerical and even now books by women are reviewed less often than books by men. Other versions/similar experiences are described by BIPOC and LGBTQ+ and other marginalized communities. We/they are excluded from the conversation about the great American novel and were we to write it would be sold and markets as the great American immigration novel, the great American gay novel, always with a modifier. We like to think so much has changed. But how can we expect women (and others) to write the Great American Novel when they are too often denied the Great American Experience?

Let’s be real just saying that was scary—much scarier than writing my book.

As I get older I am becoming more radical. On the outside I look like fit into American society. People look at me and see a plump, white, non-threatening mom person. That position sometimes makes me invisible but also gives me freedom. And I will use whatever privilege I have to make space for and bring in a wide range of voices who have previously been heard.

____________________________

A.M. Homes The Unfolding is available now from Viking.