A Liturgy, a Great Release: On Becoming My Wife’s Writing Partner at the End of Her Life

Robbie Quinn Remembers the Labors, Commitment, and Love of His Wife, Tallu Schuyler Quinn

When my wife Tallu died from a brain tumor in February, it happened how her doctor had said it might, and how all the books and pamphlets and friends and family said it might. It was a labor for her, and an event that left us in the room wailing and helplessly choking on tears. The last few hours of her breathing didn’t even seem like hers, but we all still waited for the last, slow one to come as if it was the last bit of her we would ever remember. Our two young kids were there sitting, listening to her, listening to the rest of us, and watching it all happen. And she lapsed into stillness.

Beyond the initial diagnosis of glioblastoma in July 2020, an often terminal cancer which we shockingly discovered after she had started losing vision on her right side, one other surprising development was that we became writing partners. Before then I had helped her with a few speeches for fundraising events as she developed and grew The Nashville Food Project, an organization that connects people through community gardening, food recovery, and hunger relief. But we had kept our reading and writing mostly to ourselves until then, perhaps because of our busy job-filled, two-kid lives.

Two days before a surgeon removed as much tumor as possible, she let go of her job completely and instead began dedicating her time to documenting and unpacking the sorrow and the joy of this trying time. As she wrote about her own likely death, she brought the same simple conviction to such a paramount topic as she brought to her former meetings about food justice. Her chemotherapy and radiation treatments after the surgery left her unpredictably tired and nauseous, but she kept up her daily writing effort, sometimes during restless nights, and began posting her missives in an online journal.

And we kept up our habit of reading together, whether it was chapters from Wendell Berry’s Hannah Coulter, an article from the Nashville Scene, or parts of Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer. Eventually she just used my reading to fall asleep, but it helped me feel like we were sharing it together, especially when the time came that she had so little she could say.

Her commitment to writing became a marital, and community, event. She couldn’t handwrite any thoughts because the hand-eye connections became too slow, and her lovely cursive had become jagged. Instead her friends and I helped her set up accessibility features on a phone and laptop. After she dictated to the phone, she then edited by tilting her head to discern her own paragraphs on the computer. Then after she made a pass through the pages, I would read the rough essays back to her to get a full sense of them. She was a stickler for finding the optimal phrasing and sentiment for her prose, and although our confidence in our marriage, and all the necessary communication therein, had never been greater, we clashed often over the writing.

I struggled with how many small edits to recommend, not just because of her impeded sight but more due to how ultimate the project was to her and all of us. Her whole literate life she had been scribbling thoughts, journaling, keeping travelogues, composing letters, jotting down recipes, and writing sermons in longhand, and we were now trying to consolidate it all, and the intensity of her cancer experience, into one collection. How could anyone, even her husband, feel that they could get in the way of her process, yet at the same time would we be doing her own fierce persistence a disservice if we didn’t?

During her naps and walks, her friends and I sorted through her mountainous piles of Moleskine journals and old notebooks from life stages long past. In one phase of sorting out and prioritizing her pieces, she had decided with us to structure the book like a recipe or a cookbook. Later, and more thoroughly, we designed it as a liturgy. Eventually in preparation for the book manuscript, Tallu took the advice of her agent and editor by letting the essays we loved the most, and the parts that seemed indelible, dictate the flow of the book.

During her writing year, she had two seizure episodes that sent her to the ER. She started taking more steroids to keep the brain swelling down, but nothing was stopping the slow progress of the tumor in her language center. By Fall 2021 she could still perceive most words on a screen but had to create her own phonics for slowly processing their meaning. A few months later it was clear she couldn’t meaningfully write and could only generally listen. Once when she sat with her cousin Margo, who had helped her write, taken walks with her, and even woven her a radiant burial shroud, Tallu casually said goodbye to her by lovingly misspeaking, “I love you, my sneeze.”

The whole book process had been a course of treatment for her, or a great release, and the final result contains all the connections and threads that her momentous life will always hold together. She included all of the powerful daily mantras that had emerged from the community of the Nashville Food Project, a Wendell Berry poem from our wedding, and the lyrics from one of the most poignant songs written by her songwriter dad.

And after looking through many of her own sermons and speeches from the past decade, she had condensed her favorite thoughts into funny, gut-wrenching homilies. All in the spirit of crafting one singular, hardback mission statement for her life and death. Before anyone else close to her was able to anticipate the full reality of her condition, she had already left something behind for us all to understand better what she was learning.

As we gear up for the book release now two months since we buried her in that colorful shroud, I’m reluctant to embrace how final her words seem. She will never be able to write anything again, and this book will never be enough to release me from my grief, even though I will go back to it often, along with the books and stories I read to her over the last two years. When the kids and I opened up the box of early copies in our kitchen, we started sliding our hands over the covers, and our nine-year-old daughter Lulah perched up in a chair and spent a rare quiet hour poring over the chapters. Our family has been in suspended animation for two years, but that moment felt like we could start to wake up a little.

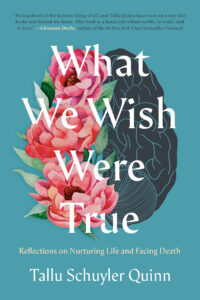

I never thought one 5”x 7” book could have such a hold over me, and I’m excited to shelve a copy here at home with all of her journals, school notebooks, artwork, to-do lists, birthday notes, sermons, aprons, t-shirts, homemade salve, overalls, and recipes. However you might find the words she wrote for What We Wish Were True: Reflections on Nurturing Life and Facing Death, I hope you know that, much like the labor of her death, Tallu opened her heart wide when her body was closing in on her. And from cover to cover she seems to be saying to us all, “I love you, my sneeze.”

_____________________________________

Tallu Schuyler Quinn’s What We Wish Were True is available now via Convergent Books.

Robbie Quinn

Robbie Quinn has been a school librarian, teacher, and debate coach in Nashville, TN. His wife Tallu Schuyler died in February 2022 of a brain tumor called glioblastoma, and he lives with their two kids in Nashville, where he and Tallu grew up.