A Kind of Mutuality: Christina Sharpe on the Importance of Regard

In Conversation with Maris Kreizman on The Maris Review Podcast

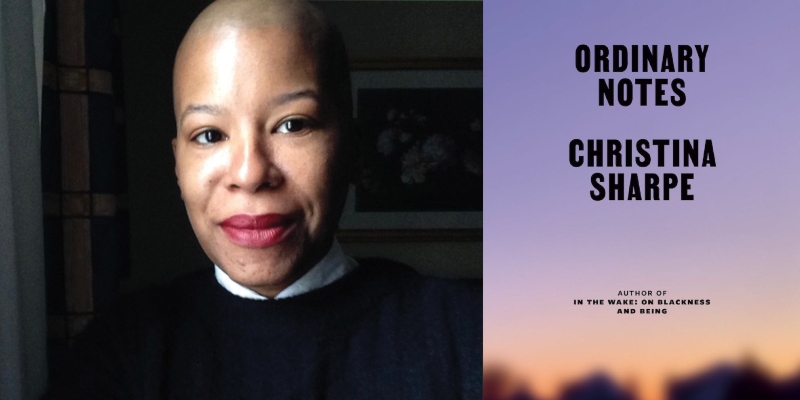

This week on The Maris Review, Christina Sharpe joins Maris Kreizman to discuss her new book, Ordinary Notes, out now from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Subscribe and download the episode, wherever you get your podcasts.

*

From the episode:

Christina Sharpe: This thing called objectivity is often the position of those who are in power, of those who, in the context of North America, don’t have to claim that they’re raced subjects or gendered subjects or sexed subjects. And so that unmarked point of view gets to pass as the objective, but of course, it’s deeply subjective. There’s no way outside of that fact. That doesn’t mean that one speaks from, writes from, thinks from that position.

There are all kinds of ways that we can undo the ways in which we are positioned, but nonetheless, that is not objectivity…. Science and math get thought of as objective, but we see the ways in which anti-Blackness is deeply embedded in scientific research and the kinds of work that people are doing to disentangle that, and undo and redress the harms that have been done by that.

You know, things about pulmonary research, kidney research, skin, Black people’s skin still appears in scientific and medical textbooks as supposedly thicker than white people’s skin. So those kinds of things have done and continue to do immeasurable harm. And so all of these kinds of discourses that presume or insist on their objectivity are oftentimes deeply anti-Black.

Maris Kreizman: Let’s go back to a part of the book that we haven’t really talked about yet, which is violence and bearing witness to violence and how we take in our past. You write, “spectacle is not repair.” And I think that’s a lovely way to think about all of these various plantation tours and museums.

CS: Yeah. I’d also wanna say, of course, spectacle is not witnessing. Witnessing involves a different kind of activation of the body, the mind, the senses. Spectacle is about capture. And so I think that one could also have vastly different experiences of those museums. I think in note three I talk about the Nazi Documentation Center in Nuremberg and how surprised I was to be there and to realize that’s doing the particular work of documenting the oppressor.

Nonetheless, how to cut that documentation in such a way that doesn’t present it, or that people don’t imbibe it, as aesthetically interesting or desirous. It was not at all the experience that I expected to have. So that’s both the good work that these places want to do, and then there’s the danger of reproducing the materials of oppression in such a way that makes clear that one can’t presume a “we” who is entering into those spaces to learn “never again.” It’s such a fraught and important project of memorialization, one that I think has unexpected outcomes.

MK: I was first reading this book when Harlan Crow was in the news, and there were so many essays about how, just because he collects a little Nazi memorabilia…

CS: Doesn’t mean he’s a Nazi. I mean, don’t we all have some bits of Nazi insignias around our house that we show to people?

MK: Who doesn’t have a sculpture garden?

CS: That’s, I think, what Claude Lanzmann means by the violence of understanding. It’s an understanding that actually works to excuse as opposed to an understanding that wants to undo or repair.

MK: And connected to that idea, you mentioned this was in Katrina Browne’s documentary about her family’s history.

CS: Traces of the Trade: A Story From the Deep North.

MK: The idea of trying to go from guilt to grief in terms of grappling with the past.

CS: Yes. That’s a documentary that I used to show all the time, and I have some problems with it. But one of the things that I do admire about it is Katrina and several other of her family members feel commitment to grappling with what one of them calls, I think, the conspiracy of silence.

Guilt is a kind of distanced relationship. Grief, I think, speaks about entanglement. I keep using the word entanglement, but grief, I think, positions you inside the thing, and guilt positions you at a distance. And so that movement is a movement that says, this is my history and I have to do something about it.

As opposed to, I feel so bad, and then moving on. Grief is something that also engages the whole body, and it says that I’m actually in this. It’s a difference between working on something because you know that you are somehow implicated in it and it affects you, versus allyship, which is again a kind of distance positioning. And a kind of philanthropic position as opposed to like, this is my work to do.

MK: And then later in the book you talk about the [Schutz painting] that was on display at the Whitney Museum. I’m gonna quote you: “The argument over representation, circulation, violence, and consumption gets nodded up, bogged down, and derailed over the question of censorship.” I’ve been thinking about that a lot, partly because we see so many “free speech absolutists” these days who’ve co-opted that term to mean something very sinister.

CS: Yes. Who’ve co-opted it to mean we can speak and you can’t. It’s the desire to have only certain voices heard. I think it was misleading to call that censorship because the real question was what work—and I’m talking about the Schutz painting now—what work is Open Casket actually doing? For me it was making abstract the kind of violence that Mamie Till Mobley worked really hard to make present in order to say, look at what they have done to my son.

And so that kind of abstraction didn’t, I think, do the kind of work that perhaps even the artist wanted it to do. It’s also quite different from the rest of her work for the most part.

MK: I’m wondering if you can talk a little bit about the act of regarding.

CS: Oh, I love that question. My thinking with that sort of follows through from the work I wanted to do in In the Wake. I think the last sentence of In the Wake is something like, a sentence that I repeat I think two other times in the book: We, Black people, are constituted through overwhelming force and violence, but we are not only known to ourselves and to each other through that violence.

Because I really wanted to say something about the ways in which you can know yourself to face all forms of violence. But you can also look at other people who are in a similar position to you with something like regard. And regard is not spectacle, it’s not a gaze. It is a kind of mutuality. I really wanted to think about that kind of mutuality as a kind of practice and ethic that we extend to each other, and that we might extend to each other, that says, I see you. That is a powerful counterforce to anti-Black violence. Even if it doesn’t shift the violence itself, it is a counter to encounter someone else’s regard.

*

Recommended Reading:

Counternarratives by John Keene • Nomenclature: New and Collected Poems by Dionne Brand • On Property by Rinaldo Walcott • ballast by Quenton Baker • Quiet by Victoria Adukwei Bulley • Promise by Rachel Eliza Griffiths • Let This Radicalize You by Kelly Hayes and Mariame Kaba

__________________________________

Christina Sharpe is Professor and Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Black Studies in the Humanities at York University in Toronto. She is the author of Monstrous Intimacies: Making Post-Slavery Subjects, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being, and her new one is called Ordinary Notes.

The Maris Review

A casual yet intimate weekly conversation with some of the most masterful writers of today, The Maris Review delves deep into a guest’s most recent work and highlights the works of other authors they love.