A Holy Terror, A Common Scold, and the First Feminist Blogger

On the Trial of Anne Royall, Godmother to the Muckrakers

Bloody feet, sisters, have worn smooth the path by which you have come hither.

–Abby Kelley Foster, National Women’s Rights Convention, 1851

![]()

In the summer of 1829, more than a century after Grace Sherwood had been plunged into the Lynnhaven River in Virginia in what is generally considered the last American witch trial, a bedraggled Anne Royall took the stand at the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia to face charges of being an “evil disposed person” and a “common scold.”

The US district attorney had conjured the charges from an ancient English common law, which had long been dismissed in England as a “sport for the mob in ducking women,” especially for older women as a precursor in trials for witchcraft.

The 60-year-old Royall, “godmother of the muckrakers,” grinned in the seat of the accused for her unabashed acts of free speech and free press. According to the court’s research, England had curtailed the conviction of “common scolds” in the late 1770s at the same time it ceased hanging women and gypsies as witches.

*

Not so in our nation’s capital. For the throng of reporters that crowded the suffocating courthouse that summer, the United States v. Anne Royall—and the “vituperative powers of this giantess of literature,” according to the New York Observer—would become one of the most bizarre trials in Washington, D.C.

Anne Royall was no stranger to trials. One of the most notorious writers of her time, she had shattered the ceiling of participation for politicized women a generation before Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony entered the suffrage ranks and issued the “voice of woman” into the backroom male bastions of banking and politics nearly two centuries before Hillary Clinton and Elizabeth Warren.

She had paid dearly for her groundbreaking role as a satirist and muckraker.

Nearly half a century after Royall’s death in 1854, the Washington Post would stretch a headline across its pages with a reminder of her still haunting and relevant legacy: “She was a Holy Terror: Her Pen was as Venomous as a Rattlesnake’s Fangs; Former Washington Editress: How Ann Royall Made Life a Burden to the Public Men of Her Day.”

The Post’s backhanded compliment of Royall’s pioneering muck-raking journalism, however, missed her defining element in the art of exposé nearly a century before President Teddy Roosevelt in 1906 famously branded “the men with the muck rakes”: her take-no-prisoners humor in defense of the freedom of the press—at any cost. “She could always say something,” declared a New England editor, “which would set the ungodly in a roar of laughter.”

Anne Royall knew how to make her readers laugh, and laugh at men—a dangerous talent, especially for a freethinking woman who rattled the bones of Capitol Hill and made Congress “bow down in fear of her” as the whistleblower of political corruption, fraudulent land schemes, and banking scandals and as the thorn in the side of a powerful evangelical movement sweeping across the country.

She didn’t simply have a second act in life; she had three or four or five. Born in Maryland in 1769, her freethinking politics had been shaped in the Virginia backwoods library of her Freemason and Revolutionary War-hero husband, William Royall. Rejected by his family as a lower-class concubine, Royall was left penniless when her husband’s estate was finally adjudicated in the courts in 1823.

In debt but defiant as ever, Royall reinvented herself and launched a literary career at the age of 57. She announced her intention to publish a book on her recent sojourn in Alabama as a “serpent-tongued” traveling writer in the 1820s, introducing the term “redneck” to our American lexicon and a Southern and frontier view to an emerging national identity, and challenged the prevailing mores of “respectable” Christian women through one avenue suddenly available: the printing press.

Traipsing across the rough country as a single woman, she quickly published a series of “Black Books” that provided informative but sardonic portraits of the elite and their denizens from Mississippi to Maine. Her Black Books became prized possessions, if only for the delight of devastatingly funny descriptions of her “pen portraits.” Power brokers sought out her company—or locked their doors. President John Quincy Adams called her the “virago errant in enchanted armor.”

The anti-Mason religious fervor sweeping the Atlantic Coast and across the frontier infuriated Royall and prodded her to sharpen her witty pen in a self-appointed role as journalist and judge. The Second Great Awakening had provided the nation with one of its most critical opponents: dour and reactionary Presbyterians intent on establishing a Christian Party and transforming American politics—and Royall took them on. “The missionaries have thrown off the mask,” she warned. “Their object and their interest is to plunge mankind into ignorance, to make him a bigot, a fanatic, a hypocrite, a heathen, to hate every sect but his own, to shut his eyes against the truth, harden his heart against the distress of his fellowman and purchase heaven with money.”

Royall may have limped after a brutal attack in New England, been scarred from a horsewhipping in Pittsburgh, and lamented being chased out of taverns on the Atlantic Coast, but she relished the attention in the nation’s capital. Andrew Jackson’s secretary of war, John Eaton, would soon testify on her behalf.

The Jacksonian era’s most outlandish trial underscored an alarming witch hunt in the press, singling out Royall’s “unruly” boldness as a funny, foul-mouthed, politically charged and outspoken woman in a volatile period of religious fervor. Tossed to the heap of “hysterical” women, Royall was brandished by the federal court and subsequent historians with the shame of drunkards, prostitutes, cranks—and witches.

Royall dismissed the carnivalesque proceedings as an American inquisition—they had less to do with her “respectable” behavior and were instead aimed at her journalistic right to free speech as a woman. Why had no man, among many other equally abrasive journalists, ever been put on such a trial?

For journalism historian Patricia Bradley, in her survey of women in the early years of the press, Royall’s branding as a “virago” diminished “her travels around the new nation as its storyteller,” which could “easily have been framed heroically, and that her accounts of the new nation, appearing at the same time as Alexis de Tocqueville’s vaulted accounts, may have become equally celebrated.” But they never were.

In fact, her story is far more complicated than has ever been told. Her role as a pioneering woman satirist in a suffocating age of religious orthodoxy has been overlooked by a century of moralizing critics. The successful and enduring tenacity of her enterprising literary strategies—maintaining an independent newspaper for decades, while publishing ten books as a social critic and agitator—rarely receives as much attention as her beggarly attire of an impoverished lifestyle.

Defiant to the “bitter end,” a nautical term she helped introduce into the American vocabulary, Royall roasted the wags on the Washington scene for three decades and, hence, remained an unavoidable female symbol—and target—in an era when women were “gross counterparts” in American humor. Her larger-than-life figure grew even more worrisome for critics when Royall targeted elite women in the religious and reform movements. Such audacious tampering with the “cult of true womanhood” in that period, as historian Barbara Welter notably wrote, damned such a person—especially another woman on the fringe of society—as an “enemy of God, civilization and of the Republic.” To the defining traits of respectable womanhood— piety, purity, submissiveness, and domesticity—Royall overturned every rule as an itinerant iconoclast who had cohabitated with her husband before marriage and took a vow to expose the hypocrisy of the “church and state” forces.

To this end, as novelist Shirley Du Bois declared in her own harrowing period of political witch hunts in the 1950s, Royall’s role as a pioneering woman politico should have also distinguished her as a de facto feminist. A generation before the suffrage movement launched its call for women’s rights at the historic convention in Seneca Falls in 1848, Royall breached the accepted place of women in the halls of Congress, elbowed her way into the back rooms of political deals at the White House, and dominated the discussion of the latest news among her peers in the corridors of the national press. But her refusal to attend to the suffrage cause, above all else—especially her campaign for universal education as an entryway to public participation—set her on the margins of women’s history. Royall’s quick trigger in expressing her disgust of ignorance, especially among the elite social reformers, regardless of gender, won her few friends. Few women of her time, on the other hand, expressed such a concern for reversing the tide of anti-intellectualism and its fallout in political corruption.

Royall has been largely ignored or minimized by most histories on women in her era and conversely lionized by historians of the Masonic brotherhood, which had banned women from their covens. Instead, the enduring issues that she challenged in her time—the stranglehold of financial and religious interests in the polarization of politics, the fragmentation of national unity, the unending debates over the balance between freedom of religion and freedom of speech, the role of anti-intellectual mediums to disenfranchise the powerless from public participation, and the shifting and historic role of women in the public arena and media—make Royall’s complex story worth reconsideration today.

Her life serves as a cautionary tale of the price paid by one woman for the right to dissent; of the historical use of ridicule and satire in leveling the patriarchal claims of frightened men in power; of the small wonder of reinvention in a state of desperation; of an older woman who repeatedly rose from mishaps and refused to be silenced.

Anne Royall was warned, tried and convicted. Nevertheless, she persisted—for decades.

Here’s the coda: Anne Royall took her revenge after her witch trial. At the age of 62, she launched her own newspaper in Washington, DC, with a gaggle of orphans and carried out two decades of investigative reporting and often hilarious commentary in an increasingly divided nation as a pioneering woman journalist, editor, and publisher— effectively, the nation’s first blogger.

As a witness to the historic demonstration by Samuel Morse of his telegraph in the Capitol room on May 24, 1844, Royall recognized the first “information highway” for the nation’s communication expansion as its grid was laid along the very horse trails and rutted stagecoach lines that she had already traveled as a pioneering writer. Morse would be immortalized that day at the Capitol. Royall would be forgotten.

Nonetheless, the playful Royall couldn’t resist edging to the elbow of Morse’s tapper, insisting on her own rendezvous with history. Anne Royall was present, she informed the assistant at the key. He nodded and tapped a series of strokes, as a small wheel on his right slowly turned. Royall smiled. She didn’t bother to look around. Within seconds, the assistant reached over and retrieved a narrow slip of paper that had issued from the telegraph machine, tore it off, and then handed it to the singular newspaper editor. Royall took it into her worn hands.

“Mr. Rogers respects to Mrs. Anne Royall.”

![]()

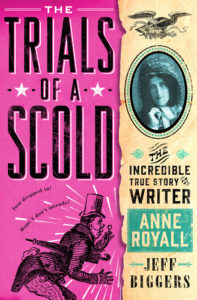

Excerpted from THE TRIALS OF A SCOLD: The Incredible True Story of Writer Anne Royall by Jeff Biggers, published by Thomas Dunne Books. Copyright © 2017 by Jeff Biggers.