A Great Musical Migration: How the Blues Headed North

On 1920s Broadway, Shuffle Along, and Northern Blues

By 1920, the blues had spread well beyond the confines of black entertainment for an exclusively black audience. In the wake of an ever-increasing demand for blues and jazz across the race line, small-time black vaudeville theaters became something they had never been before: a gateway to big-time white vaudeville circuits, burlesque wheels, and fancy metropolitan cabarets. Very early in the new decade, African Americans established fortifications on Tin Pan Alley, reconstituted the record business, and even staked a claim on Broadway, the pinnacle of commercial entertainment success.

In recognition of these developments, the mainstream entertainment journal Billboard initiated “J.A. Jackson’s Page,” allotting at least one full page per issue to news about black entertainers, written and edited by James Albert Jackson, “a Negro writer of attainments and distinction.” Jackson’s “Page” debuted on November 6, 1920, and ran every week for the next four-and-a-half years. While gathering news from across the country, Jackson focused particularly on what was doing in New York City. On August 5, 1922, he submitted an article inspired by a currently popular topical song from the Ziegfeld Follies, “It’s Getting Dark On Old Broadway.” Apparently undisturbed by its coon song trappings, Jackson celebrated the “timeliness” of its message:

In the current Ziegfeld “Follies” Miss Gilda Gray is singing “It’s Getting Darker on Broadway” [sic] . . . The lyric of the rather pretty number has to do with the recent increase in the activities of colored artists, and the favor with which they have been received along New York’s great white way. The material proof of the timeliness of the song is furnished by “Shuffle Along,” the musical comedy that has run for nearly five hundred performances at the Sixty-third Street Theater. . . .

Other indications of the darkening of the big street are the electric signs announcing the “Plantation Revue” with Florence Mills at the Forty-Eighth Street Theater and the presence of “Bandannaland” at the Reisenweber restaurant on Columbus Circle.

New York City’s appetite for black music and performers had waxed and waned since the late 1890s. The crossover appeal of blues and jazz in the 1920s had everything to do with its commercialization. An explosion of white interest created a demand for black singers, musicians, and dancers in historically segregated venues, just as it had during the ragtime revolution twenty years earlier. Broadway did get darker—all of American entertainment got darker—but the same racist machinery that had institutionalized coon songs during the ragtime era remained in place.

In the 1920s, commercialization shifted the center of blues activity north to New York City. But New York was an alien environment for the blues. As Mamie Smith, undoubtedly an authority on the subject, pointed out in a conversation with musician and journalist Dan Burley: “No real blues ever came out of New York.” Burley qualified: “The reason New York and Harlem weren’t productive in pure blues is an interesting sidelight on the situation in music in that period. Made up as it was and is of a cosmopolitan population, Harlem and New York were best suited as mediums for finished musical forms, highly polished and as commercially acceptable as expensive jewelry or other streamlined articles for sale.”

Chicago Defender, December 31, 1921.

Chicago Defender, December 31, 1921.

High polish was of little concern to the masses of southern vaudeville theater patrons who had been privileged to witness the concrete formulation of the blues in the persons of Baby Seals, String Beans, Clara Smith, Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey, and their many comrades. The blues was not a fashionable commodity to these sons and daughters of the South; it was the ripening of their regional music culture.

Perhaps the most succinct differentiation between southern and northern vaudeville was provided by a Freeman correspondent who was attempting to explain String Beans’s “comedianism”:

[W]hen String Beans and his Sweetie May came north from their Southern scenes of triumph they brought with them the best of the line of purely Negro oddities, and which were directly developed under purely Negro influence. Their offering appeared crude to the senses of Northern Negroes who had seen nothing of purely Negro origin. They had seen comedians and comedians, but these were made under the influence of white performers, consequently their impress was on them. The Northern white comedian and the Northern Negro comedian did similar work and yet do similar work. But when Beans came he introduced a different comedianism, the likes of which had never been seen in the North.

Not long before the death of String Beans in November 1917, a New York City-based Freeman correspondent observed that his “songs, actions and name are ordinary conversation in every other person’s home.” Unlike in the South, however, String Beans’s music left no obvious imprint on subsequent blues development in New York City. The blues-singing style of New York’s race recording pioneers was a jazzy sort of “polite syncopation” that was significantly removed from the blues heard in southern vaudeville. Prior to the importation of Trixie Smith, New Yorkers seem to have preferred their blues “toned down,” “polished up,” and otherwise leavened by cosmopolitan sensibilities. J. A. “Billboard” Jackson expressed the sentiment “that ‘down-home shows’ rank right along with other ‘down-home’ features and have to be revised for New York’s adaptation.”

Shuffle Along undoubtedly suited the taste of New York’s sophisticated, multi-racial theater audiences. Over the years, Broadway had been virtually closed to Negro musical comedy shows. Williams and Walker broke through the barrier with In Dahomey in 1903; their Abyssinia lasted three weeks at the Majestic Theater on Broadway in 1906; and they finally experienced actual success on Broadway with Bandanna Land in 1908. Equally notable black musical comedies such as Ernest Hogan’s Rufus Rastus, Cole and Johnson’s The Red Moon, and S. H. Dudley’s His Honor the Barber never made it to Broadway.

Shuffle Along was conceived by Aubrey Lyles and Flournoy Miller, who were also its star comedians. It featured original music by Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake. More than ten years after Bandanna Land took its final curtain call, Shuffle Along elbowed its way onto the uppermost reaches of the Broadway theater district and proceeded to turn New York City on its ear. Following a brief trial run in out-of-town theaters, it premiered at Broadway’s Sixty-Third Street Theater in May 1921 and remained for more than 500 performances.

To many minds, Shuffle Along revived the spirit of Williams and Walker. It became an extraordinary symbol of the jazz age in New York. There was nothing particularly original about its plot or cast of characters; nevertheless, northern audiences were ready for a successful black show, and the merits and qualifications of Shuffle Along defied disapprobation. New York’s theater critics, who seldom had anything good to say about African American plays or players, had to acknowledge that everything about this show was effective.

Shuffle Along took off when the rest of show business, black and white, was in its worst economic crisis in years.

This summer has been just awful, and yet, in a little meeting hall, a mile from Times Square, a Negro musical show is selling out mostly to white people who find it altogether too hot to spend an evening at one of the regular attractions on Broadway. . . .

Further, after years of the imitation, New York is now learning for the first time just what color of blue is the real Negro blue song.

“Shuffle Along” is a “wow.”

Prospects for “the real Negro blue song” in Shuffle Along were mainly filtered through Noble Sissle, Eubie Blake, and Gertrude Saunders. Sissle sang “Oriental Blues,” and Blake, “who directed the orchestra from the piano, went to the stage for a specialty with Sissle. Their first number was ‘Low Down Blues.’” Ingénue Gertrude Saunders made a pronounced hit with her “urban blues.” According to one reviewer,“Jazz with more pep than ever seen here before was featured by Gertrude Saunders . . . with her singing of ‘Daddy’ the show was stopped for ten minutes or more.”

Noble Sissle recalled: “The first soubrette we had was Gertrude Saunders, for whom ‘Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home’ and ‘I’m Craving for That Kind of Love’ had been written. She was the sensation of our show—stopped it cold every night. But like so many artists in show business who had become a sensation overnight, Gertrude, in spite of our efforts at persuasion, left the show, and we had just got started.”

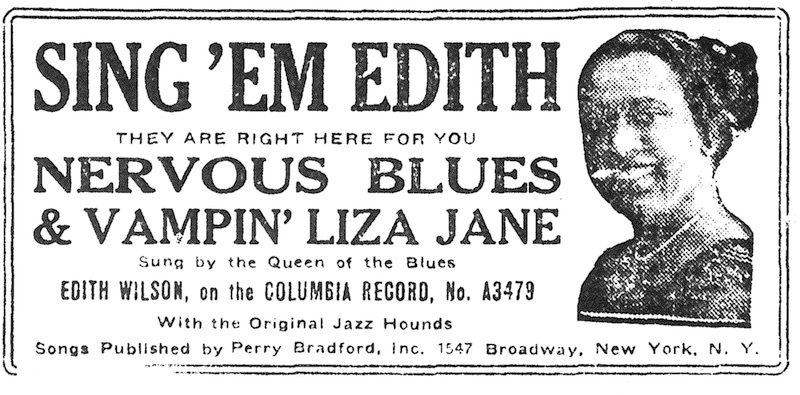

Chicago Defender, November 12, 1921. When this ad appeared in the Defender, Wilson was featuring “Nervous”Blues” and “Vampin’ Liza” in her vaudeville act at the Dunbar Theater in Philadelphia. The ad, which most likely was placed by Perry Bradford, reveals some of the ways in which various commercial interests were beginning to cooperate in promoting the blues.

Chicago Defender, November 12, 1921. When this ad appeared in the Defender, Wilson was featuring “Nervous”Blues” and “Vampin’ Liza” in her vaudeville act at the Dunbar Theater in Philadelphia. The ad, which most likely was placed by Perry Bradford, reveals some of the ways in which various commercial interests were beginning to cooperate in promoting the blues.

Saunders was adamant in later years that she “never missed a thing by walking out of Shuffle Along.” On September 3, 1921, the Chicago Defender published an upbeat letter from her: “I closed with ‘Shuffle Along’ two weeks ago and am now entertaining at Reisenweber’s. . . . Will close here on September 4, then open with Hurtig & Seamon for 35 weeks. I made a moving picture since leaving ‘Shuffle Along,’ and also made two records last week.”

Saunders made her first record for OKeh in April 1921, when Shuffle Along was just getting started. It preserves her two hit numbers from the show, “I’m Craving for That Kind of Love” and “Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home.” These are enigmatic, challenging examples of early New York City blues. “I’m Craving For That Kind Of Love” may not be a “true” blues, but there are elements of proto-jazz embedded in her ostentatious vocal flourishes. Her early experiments with scat singing may have inspired other female singers.

Possibly the most incongruous element of Saunders’s blues singing is her neo-operatic, mezzo-soprano tone. Saunders was very frank in contrasting her own voice with that of her successor in Shuffle Along, Florence Mills: “She sang a song with soul. I was a trickster. I just did tricks.” Sylvester Russell described Saunders’s “Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home” as “an art-called-for novelty.” But David Evans has characterized her recorded rendition of the song as “absurd histrionic screeching and at best a parody of blues singing.” To the modern ear, it represents an example of “Colored folks opera” run amok. At the very least, it suggests a misjudgment of where the blues was headed.

Sissle and Blake and Miller and Lyles made history a second time when they replaced Gertrude Saunders with Florence Mills. Mills and her husband, dancer and minstrel man U. S. “Slow Kid” Thompson, joined Shuffle Along together in August 1921. Mills “was hardly the earthy creature ‘I’m Craving For That Kind of Love’ had been written for, but she gave to the part, by all accounts, an ingenuousness that added greatly to the ensemble.”

Like Gertrude Saunders, Florence Mills did not stay long with Shuffle Along. In the spring of 1922 she became the centerpiece of the inaugural edition of the Plantation Revue, assembled by New York entertainment broker Lew Leslie for the fashionable new Plantation Club on Broadway: “The show has . . . created a wonderful impression in circles that count in creating favor for the Negro artist in his effort to break into the big street on his merit and on that alone.”

The opening-night production of the Plantation Revue began with Johnnie Dunn playing “a ‘mean’ horn,” followed by a vocal quartet led by Arthur “Strut” Payne singing “old-time southern melodies”; Lew Keane and U.S. Thompson executed a “craps game bit, dancing continually”; Columbia recording artist Edith Wilson and chorus sang “The Robert E. Lee”; Thomas Chappelle and Juanita Stinnette sang “several songs, aided by the six Creole girls who make up the chorus”; and Florence Mills and the chorus girls performed a “Hawaiian dance.”

It was in the Plantation Revue that Florence Mills earned her full measure of celebrity and “achieved that for which all artists strive, viz.; her name in lights on Broadway.” Mills captured New York, and London, too, before her untimely demise in 1927. Blues, even of the New York City stripe, hardly figured in her popularity.

Eva Taylor’s OKeh tribute to Florence Mills.

Eva Taylor’s OKeh tribute to Florence Mills.

Florence Mills left no recordings. She was memorialized on race records by Eva Taylor, Juanita Stinnette, and others, and was subsequently enshrined as the ideal model of a“Harlem Jazz Queen.” If the Plantation Revue included a “Harlem Blues Queen,” it was Edith Wilson. Born in Louisville, Kentucky, Wilson was introduced to the stage in 1910 by local musicians Joe and Jimmy Clark. By 1920 she had made her way onto big-time New York City stages. In the fall of 1921 she appeared in Irvin Miller’s unsuccessful Broadway production Put and Take: “This blues singer was one of the chief assets of the ‘Put and Take’ liability, and it could not have been through any fault of hers that Irvin’s show ‘blowed,’ for she is a complete knockout. ‘Vamping Liza Jane’ and ‘Nervous Blues’ are her specialties.”

Wilson maintained that it was Perry Bradford who got her into Put and Take, and then opened the door for her to make records: “Somebody from Columbia records saw me in the show, and Perry took me down to record for them. I was one of the first black singers to record, as Mamie Smith had just started things off with ‘Crazy Blues.’” She clarified her symbiotic business arrangement with Bradford: “I was his protégé, sang his songs and made them on the record.”

Edith Wilson’s 1921–22 Columbia recordings are jazzy interpretations of blues, representing the style that suited the market in New York City. Music biographers Howard Rye and Derrick Stewart-Baxter have both opined that Wilson should be regarded more as a jazz singer than a blues singer; Daphne Duval Harrison has asserted that “Wilson’s blues singing was often the only kind heard by the many whites and upwardly mobile blacks who attended the Broadway theaters and Harlem clubs.” Wilson continued to record until 1930, and she lived long enough to enjoy a second career, making records again in the 1970s with such stalwarts as Little Brother Montgomery and Eubie Blake.

The women who constituted the first wave of African American blues recording artists were all based in New York City. Commercial recording facilities were available in New York, and there were numerous black performers, composers, and producers there seeking professional opportunities. Lucille Hegamin, Alice Leslie Carter, and Daisy Martin (Trixie Smith’s three adversaries in the Manhattan Casino blues contest); Mamie Smith, Mary Stafford, Ethel Waters, Alberta Hunter, Essie Whitman, Edith Wilson, Lena Wilson, Katie Crippen, Inez Richardson, Inez Wallace, Etta Mooney, Josephine Carter, Anna Meyers, Leona Williams (Leonce Lazzo), Julia Moody, Lulu Whidby, Mary Straine, Lillyn Brown, and others recorded blues in New York in 1921 and 1922, a full year or more before Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, Clara Smith, Virginia Liston, or Laura Smith ever set foot in a recording studio.

The pioneer recordings of northern blues women reflect the urbane tastes of metropolitan theatergoers and the cultural context of the Harlem Renaissance. Typically, their singing is more self-conscious than the southern blues shouters, smoothing over the rough edges in the manner of “light entertainment.” The resonance of folk style is stronger in the recordings of southern singers, as are patterns of black vernacular speech and phraseology. Blues sentiments may be universal, but they are conveyed more convincingly by a singer with a southern accent.

Not all of the New York recording pioneers were northerners by birth; some had begun their careers in southern vaudeville. Be that as it may, these women were essentially sentimental ballad and ragtime singers who put on the blues in response to the current rage. None of the singers who dominated New York’s fashionable theaters, cabarets, and night clubs had been involved in the development of the blues. Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith’s blues evolved over the course of a decade in southern vaudeville and minstrelsy, where an endless variety of approaches were trotted out—from a barefoot trombonist to a ventriloquist’s drunken dummy to various individual takes on “Colored folks’ opera.”

“Colored folks’ opera” had one interpretation in New York City, where W. C. Handy’s compositions were presented in major concert halls as “art music,” and a rather different understanding in the Southland, where vaudeville blues was still interacting with the living folk music, grassroots idiom was still being adapted for the stage, and popular music was being creatively recycled for use as “folksong.” Howard Odum had observed this process twenty years earlier; it was the intermingling of stage and traditional music which bred and sustained the original blues.

Early in the twentieth century, formal disciplines and Western musical ideals stimulated the development of black folk and popular music culture. This constructive dynamic between African American folk music and the academy had existed for decades. A shared cultural understanding that black folk music ought to be “uplifted” contributed to the concrete formulation of the blues. Things changed, however, after the advent of “race records,” a powerful mass media for the commodification of the blues. Once the commercial promotion and exploitation of the blues began in earnest, intellectual and cultural elevation had to take a back seat.

It was sensual excitement that propelled New York City’s enthusiasm for blues and jazz. This fact was provocatively interpreted in an essay that attempted to define “the characteristic that gave vogue to the Colored Music Comedy production”:

It has been the infectious joy of the vari-colored Negro girl as she sang and danced that has prevailed over the audiences who have patronized these shows, and sent them talking. They were a genuine tonic to which amusement jaded nerves responded. It was action, incessant and joyous action, that reached the very keynote of American life and mentality that has given the colored chorus girl her place in the affections of the big impersonal American public.

__________________________________

From The Original Blues: The Emergence of the Blues in African American Vaudeville. Used with permission of the University Press of Mississippi. Copyright © 2017 by Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff.

Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff

Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff are the co-authors ofOut of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889-1895; Ragged but Right: Black Traveling Shows, “Coon Songs,” and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz; and To Do This, You Must Know How: Music Pedagogy in the Black Gospel Quartet Tradition, all published by University Press of Mississippi.