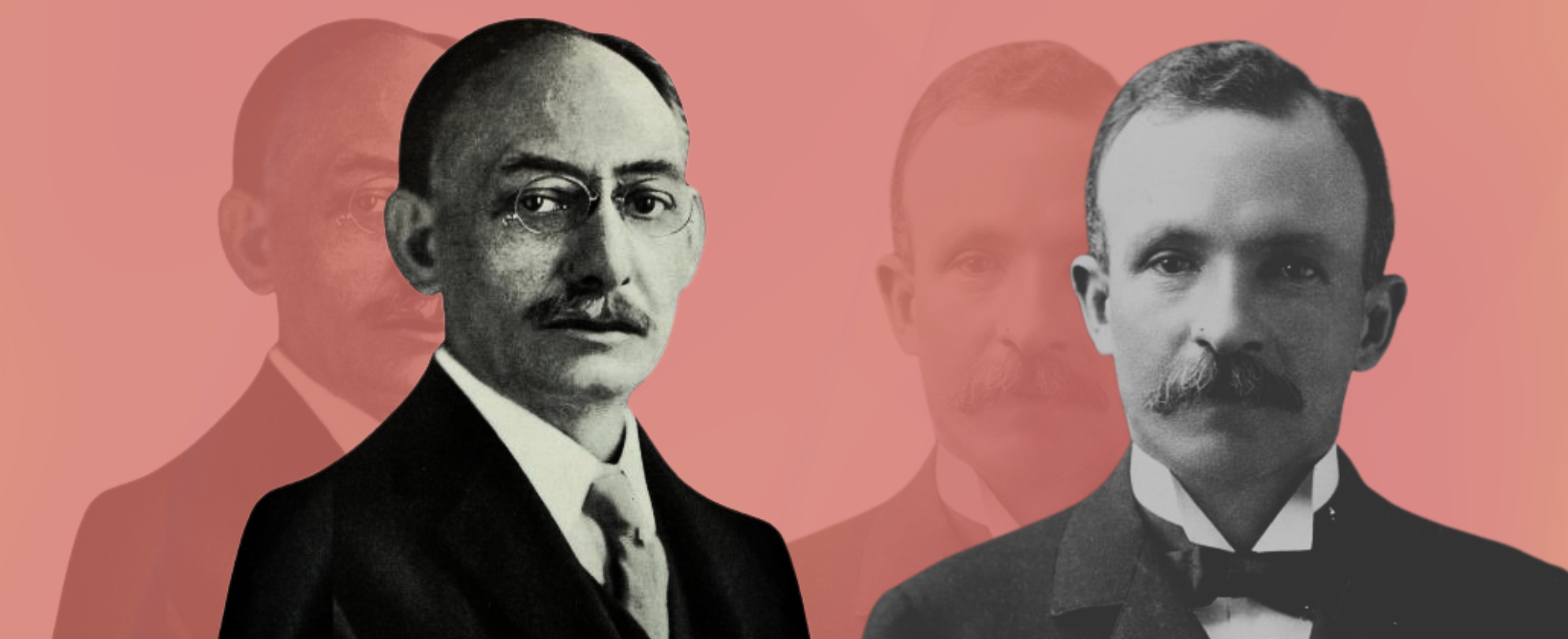

A Friendship Across the Color Line: How Shared Southern Roots Brought a Black Writer and a White Editor Together

Tess Chakkalakal on the Unlikely Literary Partnership Between Charles W. Chesnutt and Walter Hines Page

Looking back on the meeting that would launch him into the world of book publishing, Charles W. Chesnutt recalled an unusual feeling of freedom. It was September 1897. His train ride from Northampton to Boston had been surprisingly pleasant. The seats were comfortable, and there were no “For Colored” cars to strike him with the usual consternation and dismay. Here, passengers were assigned seats by number, not color. He was fortunate to have a window seat. He looked out at the pretty fall foliage, brooks, and stone fences surrounding golden meadows.

This was the New England captured by the great American authors: Hawthorne, Emerson, Longfellow, Melville. But he wasn’t thinking of these men. He was thinking of his girls, Ethel and Helen, whom he had just left at Smith College; like most parents leaving college drop-off, he still couldn’t believe they were all grown up. When he said goodbye to them at the boarding-house just a few blocks from campus, his eyes filled with tears. He hoped they would be happy. Helen’s joy balanced Ethel’s nervousness. He was glad they were starting out together. They were the first “colored girls” to set foot on the green lawns of the pristine campus. At least they would be together.

In a few days, they would begin classes at one of the country’s most prestigious women’s colleges. Helen would study Latin and then go on to teach it at Central High School when she returned home, penning a Latin textbook that would become essential reading for her students. After college, Ethel would marry Edward Christopher Williams, the first professionally trained African American librarian in the United States, who would go on to write literary fiction of his own. Chesnutt loved talking literature with Ed and was thrilled when Ethel and Ed decided to marry after she graduated. What a dashing duo they were, surrounded by books and at the center of Black intellectual circles in Washington, DC. They worked and mingled among members of the literary society her father had taught her to appreciate.

Though born into very different families, on opposite sides of the color line, Chesnutt and Page shared ideas and a common commitment to reforming—rather than reconstructing—the South.

But Chesnutt didn’t know what the future would hold for his daughters as he rode to Boston on that autumn day. He wondered what they would study and read. He loved reading to them when they were little girls. They were both the first in the family to go to college as well as the first Black women to attend Smith. Their clothes, including loafers, skirts, and sweaters carefully purchased from Rheinheimer’s, their favorite tailor in Cleveland, meticulously packed by their mother, made them appear to fit right in. Chesnutt was sure they would thrive, especially Helen. He glowed just thinking about their life at college, a life he could only imagine.

That feeling of freedom and pride at his daughters’ success dissipated by the time he boarded the southbound train in Northampton for Boston. The train pulled up at North Station in Boston, and he made his way to 4 Park Street, the offices of The Atlantic Monthly. Now he was nervous. He twisted his mustache, smoothed it down, then pulled at it again. He was sweating in his wool coat. The silk buttons, matching vest, and trousers, and his carefully tied Windsor knot, were beginning to wilt.

Charles W. Chesnutt, lawyer, stenographer, and writer, was now a fidgety, anxious mess as he sat outside George Harrison Mifflin’s corner office. Mifflin, the president of the esteemed Houghton, Mifflin and Company publishing house, held the fate of Chesnutt’s career in his hands. Mifflin was going to see right through Chesnutt’s carefully assembled attire. Behind the clothes, inside the tie, beneath the silk: Chesnutt feared Mifflin would not see an author but a parochial Southerner, and a Negro, too.

These moments reminded Chesnutt that he was an uneducated dropout who had grown up in rural Fayetteville and ended his formal education at the age of thirteen. He knew that forfeiting his own schooling to work as a schoolteacher at the North Carolina State Colored Normal School would hardly impress Mifflin and his new assistant editor, Walter Hines Page. But he waited, wiping his forehead with his white handkerchief, trying to remain calm, until Mifflin opened the door and invited him inside.

Mifflin had gone to the Boston Latin School, graduating the same year Fort Sumter fell to the Confederacy, in 1861. Rather than fighting to defend the Union, as did many of his contemporaries, Mifflin made his way to Harvard College. Mifflin was blessed with affluent pleasures. He spent winters in the family house on the corner of Beacon and Somerset and summers at Nahant, varied by frequent travel abroad.

Alongside Mifflin sat Page, a new face at the press who had just been hired as an assistant editor. There was something familiar about Page. He looked serious and formal, with his deep-set eyes, round spectacles, and double-breasted blazer. But as he spoke, Chesnutt could detect a sense of humor, one that matched his own. He had a firm handshake, and Chesnutt accepted the cigar he offered.

Chesnutt had first heard Page’s name earlier that year, when he submitted three stories to The Atlantic: “The Wife of His Youth,” “The March of Progress,” and “Lonesome Ben.” He knew these were good stories but wasn’t sure The Atlantic would be interested. It had been almost a decade since one of his stories appeared in the magazine. Chesnutt recalled with pleasure seeing his name appear under the magazine’s masthead in August 1887 when the magazine published “The Goophered Grapevine.”

Less than a year later, they accepted “Po’ Sandy.” A decade had passed. Surely, no one could accuse him of being a one-hit wonder. But the press had rejected his book proposal for a volume of stories, explaining that “we like your stories—some more than others—but our experience leads us to the conclusion that a writer must have acquired a good deal of vogue through magazine publication before the issue of a collection of his stories in book form is advisable.” This letter was not signed by a particular editor, but it reflected the editorial policy of The Atlantic’s editor at the time.

Chesnutt would later bemoan his timing. He was a Black writer who wrote years before the Harlem Renaissance flowered. Years later, he would call himself a “pre-Harlem, postbellum writer,” because without the Harlem Renaissance provenance, he could not find a place for his work on the shelves of most bookstores.

Not yet in “vogue,” Chesnutt lacked the literary reputation for publication. The trip to help settle his daughters into school in Northampton offered a good opportunity to meet the editors in person. But now he wondered if he’d made a mistake. He wanted to show all of them who he was, a writer with prospects and ideas. Chesnutt was keen to meet them, but also a little nervous. He feared their judgment. He knew too well that he was an outsider, lacking the education and pedigree that seemed essential for entry into the literary world of The Atlantic. But since he had received that rejection six years earlier, things had changed at The Atlantic. Page was interested in Chesnutt’s work; he needed to capitalize on that interest.

From its beginning, The Atlantic had been a “miscellaneous” periodical, its concerns—literature, art, science, and politics—were intended to attract a broad, but highly literate, audience. Under William Dean Howells and Thomas Bailey Aldrich, it had become increasingly preoccupied with fiction and criticism. It was under Aldrich’s editorship that Chesnutt became an Atlantic author, the first “colored” author to publish his fiction in the prestigious monthly.

But Aldrich’s forced resignation in 1890 marked a shift in the magazine’s focus, when Horace Elisha Scudder took over as editor in April. Scudder made it his mission to give more space in The Atlantic to articles on contemporary, controversial topics. Chesnutt deliberately avoided controversy in his stories. Scudder solicited articles from those with an insider’s perspective on American political life. Scudder wanted stories from men of high birth. Chesnutt was one of those that he would have considered lowly. Scudder was looking for stories about politics and courage, like Roosevelt taming the West. Chesnutt wrote about former slaves and their descendants just trying to make a living. Scudder wanted stories from insiders about insiders. Chesnutt knew he was an outsider, but wanted in. Would his stories be enough? With gatekeepers like Scudder and Howells, Chesnutt knew he didn’t stand a chance.

All that changed in 1895, when Scudder tapped Page to be his assistant and possible successor. Unlike Scudder, who had been born and raised among the Boston Brahmins and a graduate of the elite Williams College, Page was “bawn en raise,” as Chesnutt put it in a letter to him on May 20, 1898, within sixty miles of Fayetteville, where Page spent his boyhood and early manhood. Like Chesnutt, Page was a Southerner who had made his way to Boston by sheer tenacity. The North Carolina connection was only one of the reasons Page was drawn to his stories. Page thought Chesnutt’s stories “illustrated interesting phases of the development of the Negro race” and was eager to publish them “under a common heading” so that they “would produce a better effect than if published separately.”

Page knew that Chesnutt’s stories would be a hard sell among the Boston literati, but that did not deter him from finding space in the magazine for them. Chesnutt was delighted by Page’s interest but had no idea that he was also from North Carolina. To Page’s left sat Mifflin. Despite a slight discrepancy in power, Chesnutt saw the two men as equals. Page persuaded Mifflin to publish Chesnutt’s work—even though he was not well known among those who read. Page wanted Chesnutt to write more. Chesnutt was eager to produce so long as he would be published and paid. That Mifflin promised. The Atlantic paid its authors well, better than the magazines and syndicates Chesnutt had written for in the past decade. With Page’s encouragement and Mifflin’s financial commitment, Chesnutt returned to Cleveland elated, ready to write more, and shared the good news with Susan.

He got home on a Thursday night and reported to his wife what Page had told him, that his stories would come out in the December or January issue of The Atlantic. She was less interested in the meeting than she was in Boston. What was the Robert Gould Shaw Memorial like? And was the new public library as grand as she had read about in the papers? And what about Helen and Ethel? What were their rooms like? He answered her questions calmly; he was used to Susan’s obsession with the children. Helen, Ethel, Edwin, and Dorothy were her whole world. Susan’s devotion to their children was one of the things he loved most about her.

Chesnutt decided to wait and think about his meeting with the editors by himself. He lit a cigar after dinner in the comfort of his well-appointed library. It was only there, surrounded by his books, that he could think—and write. Despite his nerves and fear of rejection, he had enjoyed his meeting with Mifflin and Page. But it was Page who would become his friend and ally at The Atlantic. With Page on his side, Chesnutt knew his dream of becoming an author was all but guaranteed. So captivated was he by his dream that he neglected to find out much about Page on that sunny day in Boston. It was not until he got back home and returned to his day job as a court reporter and stenographer that he learned who Page really was.

*

It was quite unusual that Page did not reveal his Southern roots during their first meeting. Chesnutt learned Page’s backstory from Mr. Keating, a business associate from New York, a few months after their first meeting. Chesnutt had “business for several years in connection with a railroad receivership” with Mr. Keating in Cleveland.

As Chesnutt explained in his “rather personal” letter to Page on May 20, 1898: “In the course of our conversation the Atlantic was referred to whereupon Mr. Keating said that one of his best friends edited the magazine, and mentioned your name, also the fact that you were a North Carolinian by birth and breeding, and a member of the old Virginian family of the same name.” Chesnutt blamed his oversight on his own ignorance: “Of course I ought to have known all this before, but when one lives far from literary centers and is not in touch with literary people, there are lots of interesting things one doesn’t learn.” But the oversight was as much Page’s as it was Chesnutt’s.

Chesnutt’s stories were set explicitly in North Carolina. Why not mention his own familiarity with the place during their conversation? Perhaps Page had good reasons for keeping his past and family connections hidden, not only from the up-and-coming Negro author but also from his colleagues at The Atlantic—especially Mifflin, whom he needed to impress. Echoing the resentments displayed by the well-known Basil Ransom, Henry James’s controversial Southern hero introduced in his novel The Bostonians, Page kept silent about his North Carolina roots. James’s novel had been serialized in The Century a couple of years before “The Goophered Grapevine” made its appearance in The Atlantic.

When The Bostonians appeared as a novel in 1886, Scudder gave it a long and glowing review in The Atlantic. Scudder thought Basil Ransom “was a clever notion.” With Ransom, James brought “the antipathetic element from the South” to those readers of The Atlantic who had never been in the South. Scudder applauded James’s use of Ransom to represent the Southern character: “Suffice it to say that the fact of an extreme Southern birth and breeding count for a great deal in orienting this important character.” The same could be said of the real-life Southerner Walter Hines Page, upon whom James might have based his character.

Page was not a big fan of James’s fiction; he found it to be dull and tiresome, even though he did accept a few of his stories during his time as editor of The Atlantic. Perhaps Page saw a little too much of himself in James’s Ransom. Or perhaps James’s writing revealed that he hadn’t spent much time in the South. James, like the other men at The Atlantic, was more of a Bostonian than he would have liked to admit. Page was like Ransom: a man of unpredictable temper, diverging in disposition and politics from his Northern, elite colleagues.

That these two North Carolinians, living on opposite sides of the color line, found common cause in the pages of The Atlantic among the literary elite of Boston is just the beginning of a new story about an old American problem.

Page was born a few years before Chesnutt, in Cary, North Carolina. His parents, Frank and Catherine, hailed from wealthy landowning families who had built the Page-Walker Hotel, but had, like most white Southerners after the war, experienced a major financial setback. Page was eager to leave his family’s past behind him and pursue a career in journalism; but leaving the South behind, and making a home among the Northern elite, who despised his kind, proved difficult.

After a successful stint at The Forum, Page became known for frequent outbursts, perhaps due to the snobbery and prejudices of his Northern colleagues. But his friendship with Chesnutt was set apart by its display of what he frequently called “tar-heel cordiality” in their letters to each other. Though born into very different families, on opposite sides of the color line, Chesnutt and Page shared ideas and a common commitment to reforming—rather than reconstructing—the South.

There has been considerable critical speculation about the Page-Chesnutt relationship. Some, like the editor Joseph R. McElrath, believe that Chesnutt took advantage of Page’s generosity and relied too heavily on the talented editor for advice on making his work appeal to publishers and readers. Others, like the critic Robert Stepto, present Page as using Chesnutt to forward his own editorial and political career, imposing his racial views on the less experienced author.

After publishing Chesnutt’s last novel in 1905, The Colonel’s Dream, about a former Confederate soldier who moves to New York City after the war, Page moved to England, where he served as the U.S. ambassador to the United Kingdom during World War I. Since much of our knowledge of their relationship is based on their correspondence, what actually transpired between the two men is a matter of interpretation. We do know that Chesnutt and Page met frequently, exchanging ideas, and often engaged in heated conversation about the political currents of the time. Their conversation was especially concerned with the South, a place they knew intimately.

Chesnutt visited Page after attending Mark Twain’s seventieth birthday party, held at Delmonico’s in New York on December 5, 1905, where the most famous literary men and women of the time had gathered to celebrate Twain’s life and work. He was the only Black author in attendance. Page did not attend the gala event. So it was up to Chesnutt to tell his editor about all he’d missed—the food, the speeches, the clothes, and, of course, a few tidbits about the other authors who attended. There are no records of their conversations.

We also know that Chesnutt valued his friendship with Page deeply and that Page was eager to publish Chesnutt’s work. Page was especially drawn toward his work set in North Carolina. He saw it as a way to educate the North about the South, where he, like Chesnutt, had grown up and felt a deep affection, despite its many flaws. However we choose to interpret their relationship, there can be little doubt that they needed each other to tell a new story of the old American dilemma. That these two North Carolinians, living on opposite sides of the color line, found common cause in the pages of The Atlantic among the literary elite of Boston is just the beginning of a new story about an old American problem: the problem of racial and regional divisions in the United States. Chesnutt closed his personal letter to Page with a promise:

I am going to work on the novel I have been speaking of; it is a North Carolina story. With your permission I shall sometime soon write you a note briefly outlining the plot & general movement, and ask you whether there is anything in the subject that would make it un-available for your house. I am not easily discouraged, and I am going to write some books, and I still cherish the hope that either with my conjuh stories or something else, I may come up to your standard.

It was a promise Chesnutt kept and the beginning of an unlikely literary friendship between two Southerners, one white, one Black, at the turn of the twentieth century in Boston. It is a story that would change the canon of American literature forever. Charles W. Chesnutt would become the first American to write of the American dream from the Black side of the color line. But before we get to the novel that changed American Literature, we must return to the dusty streets of Fayetteville, North Carolina, where his parents met just before moving to Cleveland. This is the story of their firstborn son, Charles Waddell Chesnutt, who would dream of becoming a literary artist in a country divided by race.

__________________________________

From A Matter of Complexion: The Life and Fictions of Charles W. Chesnutt by Tess Chakkalakal. Copyright © 2025 by the author and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group, a division of Macmillan.

Tess Chakkalakal

Tess Chakkalakal teaches African-American and American Literature at Bowdoin College. Her writing has appeared in The New England Quarterly, J19, American Literary History, and many others. She is the author of Novel Bondage: Slavery, Marriage, and Freedom in Nineteenth-Century American (Illinois UP, 2011) and co-editor of Jim Crow, Literature, and the Legacy of Sutton E. Griggs (University of Georgia Press, 2013) and Imperium in Imperio: A Critical Edition (West Virginia UP, 2022) She lives in Brunswick, Maine.