My husband and I are parked on the edge of a lake, eating Subway sandwiches. We’re returning from a wedding in a neighboring city.

“It’s Karwa Chauth tomorrow,” I say, passing the water bottle to him, the moonlight laminating our windshield.

“I’ll be fasting for you,” he says, lettuce and cheese in his teeth. “Why?”

“Six months ago, when you were hospitalized and no meds could reduce your fever for several days, I made a vow. You started showing improvement after that evening. Also, I won’t be the first man to fast—”

“Until this time tomorrow,” I say, “after the moon comes up.”

He doubles back on my sentence. In this light, his eyes squint as if taking aim, his face grows tense. Outside, the surface of water glimmers. My husband has an air of mystery around him and that’s what I love about him, but it’s a long, grueling old Hindu tradition.

“It’s too hard, you don’t have to—”

He puts his hand around me. “This is for your long and healthy life. Not finishing it will have serious consequences for you.” His voice strangely deeper, fuller.

“Don’t be silly—” I kiss the crack on his chin from a childhood accident falling off the bike.

“Well, did you ever break it when you used to fast for me?” His eyebrows are raised, his forehead creased. The question hangs in the middle of the whiff of his aftershave and the warmth of our breaths tickling my nose. I move my face away and sneeze.

*

At this hour before daybreak, our bedroom looks like a view into a small spaceship. I kiss my husband on his ear when the alarm goes off. “Go back to sleep. I will go eat some sargi and drink water now,” he whispers and closes the bedroom door softly after him.

*

From the window, the darkness fades around the horizon. A violet dawn is immersed in stars.

I stretch under the sheets. No water and food for him after the sun comes up. Until moonrise. Since my childhood, my mother had been conferring upon me the rituals, the shlokas of how a married woman should be devoted to her husband. I had seen her perform the ceremony of Karwa Chauth for my father—henna on palms and feet, painted nails. Decorating the pooja ghar with flowers and rangoli and waiting for the moonrise in a starlit sky. In the first year of my marriage, my mother-in-law offered me sargi on the dawn of Karwa Chauth. A glass of sweetened, hot milk with seviyan. Observing this fast as per our scriptures brought sons and prosperity, cured illness, she said. Breaking it without seeing the moon would bring ill fate to the family, especially the spouse. Then she dabbed some sindoor along the parting line of my hair, wishing me a life of togetherness and a meaningful death as a married woman. By evening, I could hardly walk, dizzy with hunger but mostly thirst. When the moon rose, my husband stood tall—his breath fragrant with a mouth-freshening mix of coconut flakes and fennel seeds—and handed me a glass of water, my first sip in twenty hours.

“Was it all that difficult?” He grinned with childlike innocence.

*

When I get out of the bathroom, my husband is pacing in the bedroom, his right hand circling his stomach.

If I offered him food or water, he’d dismiss it, saying I don’t think he’s strong enough to finish the fast. “Hunger is an illusion,” I say. “You can do it.”

“I know, I know,” he says, irritated. The angle of the light on his face makes him look thinner.

*

My husband eyes two aloo parathas with mango pickle, a cup of cardamom-ginger chai I’ve made for myself. He licks his chapped lips.

“Do you remember the time when I told you I dreamt of parathas on the days I fasted?” I ask.

His eyes are focused on my plate. I become conscious of the way I chew the buttered bread, imbibe the sweet tea.

*

The sun is falling west. My husband decides to take a nap.

I run my hand through his hair. Shiny black locks. Deep brown forehead. They say even between what we touch, there’s an atomic gap, a gap that can never be overcome.

“This isn’t as easy as it seems,” he confesses.

I want to say, It’s only a myth, no harm done if you break it now. But I keep massaging his scalp with my fingertips. The room sinks into a deeper silence.

*

My husband looks frail as he pulls out a chair. His elbows rest on the dining table, his palms cup around an imaginary mug while I boil milk and water, stir instant coffee with sugar. The chair creaks as he leans forward. I inch the cup toward him.

“No,” he says, and gets up, hunched as if hurt by the air alone.

*

In the evening, we watch a South Asian channel playing Karwa Chauth songs, songs of devotion and love, unbreakable loyalty. Then he showers and wears a white churidar and a long red kurta, the golden chain around his neck a gift from my mother at our wedding. As night approaches, he prepares his thali to worship the moon.

Flowers, a pinch of vermillion and turmeric, a few rice grains, while I order takeout from an Indian restaurant—aloo gobi curry, dal makhani, achari baingan with tandoori rotis. He chants how Lord Shiva fasted for an indefinite time when Gauri, his wife, fell ill and there was no hope of her recovery. With his continuous fasting and reverence for his spouse, Shiva brought Gauri back to life and since then, they’ve been eternal partners.

*

We drive to the outskirts of the city where there are no buildings obstructing the sky to see if the moon has risen. October is in full bloom, crisp air, fallen leaves, frost slowly taking hold. Bunnies scurry in and out of nearby bushes. We sit in a deserted parking lot of an old industrial area. My husband is unable to stay still in his seat, his fingers fret.

“Do you want me to be your spouse again? In your next life?” “Yes,” he says, and rubs his palms together and breathes into

them. “It’s more fun to be with you than being alone, even when we’re just watching TV, or working in our offices, or talking to someone else on the phone.”

“That could be anyone instead of me.”

“Could be,” he pauses, “but I want it to be you. I don’t know— it’s like playing the same game over and again. The only thing left to do is to do it better.”

We exchange our slippers, he wears my bangle, I put on his watch. It feels like a wedding ceremony. From the windshield, the stars look as if sewn flat against the sky, waiting to be undone. Then they slowly disappear.

*

The next morning when I wake up, my head is on the steering wheel, his seat pushed back as far as it can go, his mouth open. He wakes up with a jolt.

“Did the moon—”

“I don’t know,” I say. The sky is glittering with a light so bright, it’s hard to look at it. “Let’s go home.”

“No, the moon has to be here, faint by now, but here,” he insists. “I can do it,” he whispers. I press my lips on his forehead. “Please let’s stay for some more time,” he begs. Something inside me is seized by his devotion, his belief that he might fail himself if he doesn’t go through the entire fast. Sometimes being offered a complete submission to a notion feels like the very evidence that you’ve been a fake.

*

Another night slips in, and then another. I check the news with the little charge remaining in my phone. There are no reports of the moon missing. It’s been a few days. My husband can hardly move. In the back of the car, I find a black satin eye mask, an old catalog from Ethan Allen, an opened bag of chips. A packed sandwich from our trip. An electric candle. When I take out a handful of chips for him, he looks at me and mouths, I can do it. Promise me we won’t leave until we see the moon. His breath is dry, foul, his teeth a fence. He sleeps most of the time, his head rubbing hard on the seat that is hoarding some of his hair. He’s ripping out like a stitch. Provoked by my own hunger, I pick a few chips and stop—all those years, did I fast for his long life like a dutiful wife, or was I just waiting for the hours to pass, pretending to be devoted to him? Until tired of feeling excessively hungry and inadequate on Karwa Chauth days, I stopped following the tradition. My husband said he didn’t mind, and I luxuriated in the newfound absence of rituals and beliefs I thought were blind faith.

I glance at the chips, slip them back into the bag. Inside the car, my husband’s eyes are barely open. I kiss them and want to cry. I want to pull him up, shake him with love and anger, Look at you! Why are you doing this? Please, I’m begging you, let’s go home.

I want to say, I’ll do anything, if it means you’ll live.

*

While he’s dozing, I walk toward a grove a few yards away from us. I turn on the electric candle and place it in between the farthest branches of two intertwined trees I can reach.

“The moon has risen,” I shout several times as I run back to the vehicle, unsure how long the candle’s battery will last.

He rubs his eyes, looking in my direction.

“There.” I point to the candle in the midst of the branches, barely luminous.

He folds his hands in prayer. His eyes are sunken deep in their sockets, he’s hardly awake. I put a water bottle to his mouth, swallowing a chunk of air, relieved. He takes a few sips drooling a stream from the corner of his mouth. Then he closes his eyes again. It’s getting chilly and I shiver with the excitement of returning home as I buckle his seatbelt. My body feels stiff and thin. The edges of my arms blur in the darkening air. My husband giggles in his sleep and then the sullen hum of the car fills the silence. I’m cautious as I drive back, my fingers going numb from no exercise and restricted movements.

*

Our driveway is littered with newspapers, the mailbox overflowing with envelopes and packages. Our lawn is a lively mess of the wildflowers we’d been trying to protect it from.

“It will take forever to go through this,” my husband says in his drowsy voice, his face slackened into seriousness, his left hand rubbing a circle on my thigh as I cross an ocean of junk, the tires squealing and crushing pieces of our life.

*

Inside, the house is stinking so badly I can hardly breathe. Rotting produce and cubes of decayed time. My husband pulls out the leftovers from the fridge and starts stuffing the chunks of potatoes in his mouth, the tomato curry staining his lips. He licks the empty Styrofoam boxes and aluminum foil.

*

Under the fluorescent light in the kitchen, my skin looks transparent—my muscles visible, split, the peeping bones—disappearing, atom by atom, as if self-destructing on a quiet timer. My husband drops his food and comes close, his wide-set eyes staring, his mouth opened in a shriek I can hardly hear. I try to focus but all I see is the blurry outline of his head, his shoulders, his weak arms dragging me to our bedroom, his tears soaking my skin. My nerves fire on and off, and something pulls the air out of my lungs, my eyes lidless, drying. My husband’s touch feels closer than ever, as if it’s mine. His lips are on my mouth or what’s left of it, and I can taste the food that’s a part of him with my disappearing tongue, my teeth, my hunger I held back on the days I fasted, a sensation so terrifyingly freeing and fulfilling.

From the window, the Big Dipper is sprawled across the horizon and at its edge a dull, silver arc like a boat that has slipped its mooring, waiting to be pulled in, washed anew.

__________________________________

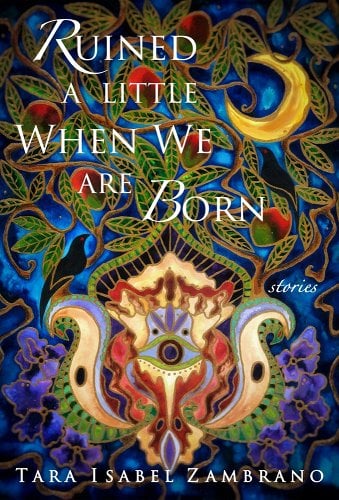

From Ruined a Little When We Are Born by Tara Isabel Zambrano. Used with permission of the publisher, Dzanc Books. Copyright © 2024 by Tara Isabel Zambrano.