A Dream Job Too Good To Be True, a Story Too Weird to Believe

Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman, Mediocre Violinist, on Playing for "The Composer"

Audition

New York City, 2002

“Is this Jessica? Jessica, the violinist?” The voice on your dorm telephone is Becca Belge, assistant manager of the The Composer’s Ensemble. Can you come to the office for an interview? Yes. Can you come right now? Yes.

The office is a few blocks away and you race down Broadway in what you consider to be your most job-interview-worthy outfit, a red-sequined blouse and white skirt, your violin case strapped to your back.

You have been working two jobs that summer in the never-ending quest to pay your college tuition, but you are coming up short. It is already June and you have less than two months to come up with $8,000 for the fall semester of your senior year. So each night, after working at your second job, you have taken the subway home, eaten a $2 slice of Sicilian pizza, and searched the Internet for a third. And each night you have noticed there are very few well-paying jobs available for twenty-one-year-old college students that do not involve sex work.

But then you came across a posting on a student LISTSERV:

Seeking violinists and flute players to perform in award-winning ensemble that has performed on PBS and NPR and at Lincoln Center. Must be able to work every Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. $150/day with potential bonuses. Send résumé and demo tape to Becca Belge, Assistant Production Manager.

You had never seen an advertisement like this. Professional ensembles, whether classical, folk, or punk rock, do not place advertisements on college LISTSERVs, and they hire by audition, not by an open call for demo tapes.

You read the ad again and again. If you got this job, you would double your current income. More than that, you would become what you had spent your childhood dreaming of becoming: a professional violinist.

One problem: You aren’t very good at playing the violin. You dropped your music major shortly after arriving at college. Your freshman dormitory alone housed dozens of better-than-you violinists. Looking at the strange job ad, you began calculating how many better-than-you violinists might exist on the Upper West Side (hundreds), in Manhattan (thousands), and all of New York City (millions?!).

Still, you decided to try, enlisting a friend who worked at the student radio station to help you record a demo tape. Before the recording session, you practiced for hours. You planned and replanned which pieces to include on the tape and in which order—fast tempo, slow tempo, fast tempo; Bach, Corelli, Mozart; technical, expressive, technical; a piece to showcase the fingers, a piece to showcase the bow, a piece to showcase the vibrato. You revised your résumé to make yourself seem more musical. You dropped your application into a mailbox, thinking to yourself: At least you tried.

Three days later, Becca Belge hustles you into a dark two-bedroom apartment full of dumpy-looking office furniture. Stacks of CDs teeter on top of the stove’s burners, microphone cords snake around the kitchen floor, piles of sheet music overflow from the windowsills.

Becca is a tall, round woman with red hair and a red face. She wears a t-shirt, denim skirt, and plastic flip-flops. She offers you a metal folding chair and you say, Thank you, Ms. Belge, and she booms Call me Becca while ransacking a file cabinet, flinging sheet music onto the floor. You sit on the folding chair with your violin case in your lap and attempt to steal glances at the sheet music. At any moment Becca will ask you to sight-read it, and you know that your lack of sight-reading skills will doom this audition, will separate you—the hardworking but untalented person who mailed in an acceptable demo tape—from the job applicant who is gifted, the prodigy who can perform any musical score at first glance.

“Here it is,” Becca says, holding out a sheet of paper.

What is it? Some impossible Dvořák concerto? A finger-twisting Kreutzer étude? A Bach partita that will make your chin crunch into your violin while you saw and scratch and reveal yourself to be an amateur posing as the real thing?

But it isn’t sheet music. It’s a W-4 tax form.

You’ve had enough jobs to know that filling out a W-4 means you are hired. But how can you be hired? You haven’t played anything. You haven’t even been interviewed. Becca isn’t asking you any questions. She is telling you to complete the W-4 and you are nodding and filling it out and she is asking if you have plans for the weekend.

“Because if you don’t,” she says, “we need you to go to New Hampshire.”

“Okay,” you say, as if going to New Hampshire is something you do all the time. You’ve been north of New York City once, for a night visiting a friend in Boston. New Hampshire?

“New Hampshire!” Becca is saying, adding something about Yevgeny, a Russian violinist who is to meet you on a Manhattan street corner on Thursday night. He will drive you to New Hampshire where you will meet up with Debbie, a flute player. The trip to New Hampshire will be your “training weekend,” and it will be your job to sell CDs during the live concert.

“So, should I bring my violin?” you ask, confused.

“You probably won’t need it, and there won’t be much space in Yevgeny’s car,” Becca replies. “But if all goes well with the training,” she assures you, “you will work as a violinist the following weekend.”

Becca hands you a stack of sheet music and nine CDs. The CD jackets feature bucolic scenes—a blossoming tree, a lighthouse, a meadow by a stream. Written across the top of every CD cover is the name of The Composer.

“Who is he?” you ask.

She gestures to the CDs. “This is all his music.”

You have never heard of The Composer, but you don’t say anything to Becca. Instead you make a face like, “Ah, yes, of course! The legendary Composer!” Three years at college have taught you to avoid being, in the words of one future Rhodes Scholar and congressman, “that twit with the Southern accent.” Since then you’ve discovered that, thanks to the Internet, even a twit with a Southern accent can learn what she needs to get by.

Who is the Composer?

What the Internet says:

The Composer has sold millions of albums. His benefit albums for charity have reached No. 1 on the Classical Billboard chart. Hollywood A-list celebrities narrate his PBS specials, which have raised millions of dollars for public television. His conducting credits include the most prestigious orchestras in the United States and the world.

He has performed with orphans in Africa and was sponsored by the U.S. State Department to spread goodwill in communist countries. He provides free CDs to American soldiers in the Middle East. His compositions stream through hospital speakers across America and are thought by many to have curative properties.

In less than fifteen years, The Composer has released over thirty albums of his compositions. He regularly appears live on the QVC shopping channel, where his albums sell by the thousands per minute. Purchasers of his CDs leave orgasmic online reviews like “my heart is tingling,” “the world’s most beautiful music,” and “this music is my personal opiate.”

God Bless America Tour 2004

Philadelphia to Atlanta

The Composer spends most of his time in the back bedroom of the RV, composing. He has few reasons to emerge, for everything he needs is on top of his bed: a full-size keyboard, folding chair, two bookcase-length plywood boards, a dozen stuffed animals, enough dusty concert wires to amp the New York Philharmonic, a film projector, half-empty boxes of Cap’n Crunch, a crate of apples, a pungent pile of running clothes. While the rest of us sleep in hotel rooms, The Composer sleeps in the RV every night, presumably on top of the keyboard.

Per The Composer’s orders, one of us—me, Harriet, Stephen, or The Composer himself—rides in the passenger seat with Patrick at all times in order to help him navigate and to DJ Patrick’s favorite road tunes on the RV’s sound system. His favorite road tunes, Patrick insists, are all of The Composer’s albums. As official Ensemble musicians, The Composer’s employees, and people spending most of our waking hours with The Composer, objecting to Patrick’s choice of music has obvious perils. Then comes our first thirteen-hour day on the road and Harriet (passive), Stephen (avoids confrontation), and I (wimp) threaten bloody mutiny if we have to listen to another goddamned note. The Composer stays mum on the issue, but I suspect that even he doesn’t want to listen to his music any more than he has to.

Of all of us, Harriet has the best taste in music. When not on tour, she lives in Chicago, where she plays in symphony orchestras during the day, swanky clubs at night. She has rare demo recordings of Chicago musicians who went on to be famous. Everyone wants to hire Harriet as a violinist. She’s gorgeous yet old- fashioned, the sort of person who punctuates her speech with phrases like “Bless your soul” while flashing a killer smile. She’s agreed to the God Bless America Tour because she wanted to get away from a complicated situation with a man back home. It felt like the right time to go on a road trip.

Thirteen hours in an RV is a lot of time to listen to music. As the RV barrels south into the hot yellow light of late August, we listen to country, rap, hip-hop, bluegrass, classical, jazz, classic rock, gospel, grunge, Broadway, indie, and blues. The trees get taller and leafier, the cornstalks higher. The soil turns blood red and we are in Georgia.

Somewhere in rural northern Georgia, I decide to play the first movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. The moment I push the Play button I hear The Composer flailing his way up the cabin toward us. He perches in the space between Patrick and me, listening to the music, the infamous swelling variations on da da da dah—perhaps the four most recognizable notes in human history.

And then, The Composer asks me a question that—had it come from any other musician, let alone a Billboard-topping classical composer who has performed with the New York Philharmonic—I would have taken as a joke. But The Composer is sincere, speaking in the friendly just-making-obligatory-chit-chat-with-the-help voice he uses with me, the person whose name he thinks is Melissa.

“I like this music,” he says of the opening to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony. “What is it?”

Imposter Syndrome

After your interview with Becca, you float up July-drenched Broadway back to your dorm, past the roasted-nut vendors, the incense peddlers, the sidewalk displays of used books for sale, the lone saxophonist outside the West End bar who plays the theme to Sesame Street over and over again. Sunny days . . . You clutch your sheet music and CDs, their plastic covers sweating in the heat.

You have gotten the job. A violin job! You feel like a violinist in a way that you never have before, despite thirteen years of practice, lessons, and school performances. All of your years of practicing are going to “pay off,” that distinctively American phrase that conflates all work with reward, all positive outcomes with money.

But it isn’t just the money. You can tell your parents, your high school teachers, and all of the adults in your rural hometown who supported you—from setting up the folding chairs at high school concerts to driving you to auditions to sending you cards of encouragement (one from your eighth-grade science teacher: You have a real gift! We are all so proud of you! Never stop practicing!)— that all of their hard work, and all of yours, will amount to something. It doesn’t matter that you weren’t born a prodigy. It doesn’t matter that you aren’t as good as the other violinists at Columbia. It doesn’t matter that while those kids were taking lessons at Julliard and giving concerts at Carnegie Hall, you were performing solos in your school’s “auditorium,” which was also your school’s cafeteria and gym, the nearest real auditorium hours away over the mountaintops.

None of that matters because you have worked hard and “made it,” another distinctive American phrase. And, If I can make it there, I’ll make it anywhere . . . Years later you will question the way this phrase has warped your consciousness. You will discover that “make it,” as an expression, emerged in the American vernacular during the Gilded Age. The wealth disparities of that era are reflected in “make it,” which evolved to mean both mere survival (make it through the winter) and wild success involving money, fame, and/or acclaim (make it big), forever linking these two vastly different outcomes in the American mind.

But for now you simply think to yourself that you have “made it.” You are the kid from the rural South—Appalachia no less!—that twit with the Southern accent. Who has Beat The Odds. Start spreadin’ the news . . . You are it. You are proof. The real deal. (The money!) You are a professional classical violinist in New York City.

Then you think No, this can’t be right. You aren’t good enough to be a professional classical violinist in New York City. There has been some horrible mistake.

__________________________________

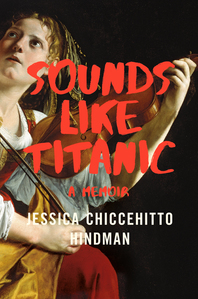

From Sounds Like Titanic. Used with permission of W. W. Norton. Copyright 2019 by Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman.