A Desi Mr. Darcy: Sayantani DasGupta on Diverse Retellings of Regency Tales

“Maybe the sort of multicultural representation we see in recent Regency romances can be a kind of medicine.”

It is a truth universally acknowledged that everyone loves a good Jane Austen remake. From Alicia Silverstone’s Clueless to Bowen Yang’s Fire Island (a gay, and mostly Asian American, Pride and Prejudice), to the forthcoming Netherfield Girls starring Maitreyi Ramakrishnan of Never Have I Ever fame, Austen’s stories of love and courtship in 19th-century England continue to shape our ideas of modern-day romance.

Dakota Johnson’s portrayal of a manic-pixie-dream Anne Elliot notwithstanding (see, or don’t see, the recent wink-wink nudge-nudge “aren’t I such a wacky lady?” remake of Persuasion at your own risk), Regency romance appears to be just the soothing balm our collective psyches need.

As a Desi Austen lover myself, I’m particularly thrilled by the wave of color-conscious casting of Regency tales, from Shonda Rhimes’ delicious Bridgerton and Queen Charlotte to Emma Holly Jones’ Mr. Malcolm’s List, which stars not only Freida Pinto in the romantic lead, but has her love interest played by—gasp!—another person of color, Sope Dirisu. (Like the Bechdel test, which tests for gender stereotyping in film, I have my own personal DasGupta test for rom-coms in which both partners are people of color. Sorry to say they’re still few and far between.)

What does it mean to re-envision an all-white novel with BIPOC contemporary characters?

Even the Indian film industry seems obsessed with creating Austen remakes, perhaps related to the fact that the cultural focus on courtship and marriage is alive and well in South Asian communities. Examples include the 2000 Tamil language Kandukondain (a Sense and Sensibility revisitation) to the 2010 Emma-inspired Aisha to London-based director Gurinder Chadha’s 2004 Bride and Prejudice.

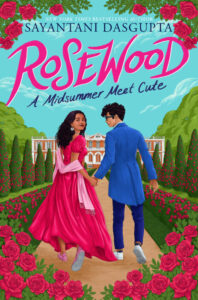

There have been a huge number of Austen reimaginings among Desi YA and adult novelists as well, including Soniah Kamal’s Unmarriageable: Pride and Prejudice in Pakistan, Sonali Dev’s Pride, Prejudice and Other Flavors, Uzma Jalaluddin’s Ayesha at Last, Mahesh Rao’s Polite Society, and my own contemporary YA novels, Debating Darcy and Rosewood: A Midsummer Meet Cute (best described as Sense and Sensibility meets Shakespeare meets Bridgerton).

I was introduced to Jane Austen-ji/Jane Mashi by my mother during one of the many summer vacations we would take to Kolkata, India, traveling from our home in Ohio and later New Jersey to spend the three months of my school holidays with our extended family. The afternoons were hot and long, but my book-loving grandfather’s dusty bookshelves were stacked three rows deep with the world’s best literature. And despite being a once-jailed Indian freedom fighter, his collection did lean heavily toward the British. (As a Desi friend of mine is fond of saying, even our literary tastes are colonized beyond repair. Two hundred years of British rule will do that to a people.)

It was on one of those long summer trips that my mother handed me my first Austen novel, Pride and Prejudice. Despite some initial resistance on my 12-year-old part, Austen’s timeless story of five unmarried sisters managing friendship, love, and the rules of a rigid society quickly captured my imagination, giving birth to a lifelong obsession with all things Regency and romantic.

Since then, I’ve revisited all of Austen’s novels (except, maybe, Mansfield Park—begging pardon of all you Fanny Price stans) dozens of times. If it was the courtship and romance that initially drew me to Austen’s work, what’s kept me coming back is Austen’s famous wit and her razor-sharp ability to use humor as a tool of social critique. In re-imagining Austen for a contemporary teen audience, it was that quality I wanted to capture.

But while Austen uses humor to examine, among other things, gender roles, classism, and unfair inheritance laws, I turned my eye to gender, class, colorism, colonialism, and racism, not to mention bringing a #MeToo consciousness to that slimy sexual predator Mr. Wickham in my Pride and Prejudice reimagining.

But what are we doing when we cast Austen adaptations, or any Regency story for that matter, in a color conscious way? In other words, what does it mean to re-envision an all-white novel with BIPOC contemporary characters? Am I, a brown-skinned immigrant daughter who never got to read about or see characters like me in novels and films, simply reclaiming these beloved stories as my own—declaring that Jane Austen belongs to all of us? Or am I actually letting these stories off the hook, ignoring their oppressive aspects in their very recasting?

This is one of the many arguments in Debating Darcy between rival high school debaters Leela Bose, my Bengali-American Lizzie Bennett, and Firoze Darcy, my Pakistani-British-American Fitzwilliam Darcy. Instead of arguing about Austen, they argue about Lin Manuel Miranda’s BIPOC-cast play about the life of Alexander Hamilton, the musical phenomenon that arguably set the stage for our current spate of color-conscious Regency stories:

“The thing is… it’s just that… I mean, to be honest, I don’t like Hamilton… Everyone seems to think it’s so edgy.” Darcy had his legs crossed, ankle over knee, and his fingers tented under his chin. “In actuality it’s just a weak apologist play that lets a bunch of racist enslavers off the hook, makes them seem palatable and cool.”

“Did you read that hot take on social media or did you come up with it yourself?” I snapped. I mean, we were talking about my favorite play here. What kind of a monster didn’t like a clever hip-hop musical about America’s founding fathers?

“Oooh! Thomas Jefferson couldn’t have been a rapist, the guy who plays him is hot and he can rap really fast,” Darcy said in a scornful voice.

“It’s a legendary moment in musical theater history, in which brown and Black folks got written into the story of America for once. In which we got to see ourselves as the protagonists,” I argued.

Article continues after advertisement“Why do we need to co-opt the majority’s stories and insert brown and Black faces into them?” shot back Darcy. “Why can’t we just write our own?”

“Why can’t we do both?” I demanded. “We’ve been silenced for so long. Can’t we find multiple ways to express ourselves, speak, and have our voices and stories heard?”

Even though Austen’s novels were written before the official beginning of British rule in India, Desi adaptations of her stories—including my own—can be accused of distracting from more critical readings of her work and its relationship to colonial rule. On the other hand, they might give permission to young Austen fans of color, like I once was, to see themselves more fully in her work. Rather than offering any firm solution to this tension, I have chosen to let my novels sit in it, having my characters themselves reflect upon this push-pull problematic between representation and critique, co-option and adaptation.

Rather than offering any firm solution to this tension, I have chosen to let my novels sit in it.

Set in a summer regency camp which is scouting young multicultural extras for a Bridgerton-like television show, Rosewood engages with the tensions of color-conscious casting head-on. The group of brown and Black, queer and straight theater kids attending the camp have multiple conversations about the very issue, demanding at one point that there be more queer BIPOC representation in the novel’s titular show.

Eila Das, my Elinor Dashwood stand-in, enters the camp’s imposing mansion setting in the same way she and her fellow actors seek to enter the world of Regency stories: “Think of it as a subversive act,” Eila’s love interest, Rahul, says. “How Queen Victoria would squirm to see two brown ex-subjects like you and me here doing this.”

When I was young, I never got to see myself—or anyone vaguely like me—in the stories that I loved. This lack of representation convinced me, at some deep level, that someone like me was not worthy of being seen as a hero, a love interest, or a protagonist of an epic tale. And if I was not worthy of being represented as a hero, maybe someone like me couldn’t be a hero even in the story of my own real life.

If narrative erasure is a kind of psychic violence, maybe the sort of multicultural representation we see in recent Regency romances can be a kind of medicine, a storied healing for those of us who have too long been ignored, erased, or vilified. Or maybe it can be a representational thumbing of the nose to those who kept our ancestors barred at doors declaring “No dogs or Indians allowed.”

Is a brown Elinor Dashwood or a Desi Mr. Darcy enough to heal all our psychic wounds—postcolonial, representational, or otherwise? Of course not. But it’s a beginning, a start of a new sort of literary and historical imagining in which we all belong and we are all celebrated.

As Regina Rivera-Colón, Rosewood‘s Shonda Rhimes-like writer-director declares, “Not all of us, growing up, were allowed to dream of beautiful things. Not all of us, growing up, were allowed to think of ourselves as the protagonist of the story. [But] all of us deserve to be a part of the fantasy. All of us deserve to celebrate the magic that has always been there, inside ourselves.”

__________________________________

Rosewood: A Midsummer Meet Cute by Sayantani DasGupta is available from Scholastic Press.

Sayantani DasGupta

Sayantani DasGupta, MD, MPH, is a pediatrician by training, founder and faculty in the Master’s Program in Narrative Medicine at Columbia University, holding additional appointments in the Center for the Study of Ethnicity and Race and the Institute for Comparative Literature and Society. She is also a New York Times bestselling author of over a dozen novels for young people, including the critically acclaimed, Bengali folktale and string theory-inspired Kiranmala and the Kingdom Beyond books, the first of which—The Serpent’s Secret—was a Bank Street Best Book of the Year, a Booklist Best Middle Grade Novel of the 21st Century, and an EB White Read Aloud Honor Book. Sayantani was a long time team member of We Need Diverse Books and is a founding member of Authors Against Book Bans. You can find out more about her work at www.sayantanidasgupta.com