A Constant Reinvention of Language: Looking Ahead to 2025 in Poetry

Rebecca Morgan Frank and Christopher Spaide Showcase Some of This Year's Most Exciting Forthcoming Titles

Happy New Year, Poetry Readers! I am happy to welcome Christopher Spaide as the new co-curator of this monthly poetry round-up. This year promises new collections from poets such as Henri Cole, Shane McCrae, Allison Benis White, Mónica de la Torre, Harryette Mullen, Cedar Sigo, and Martin Espada. Rest assured, we will continue to seek out a range of voices and presses all year long. For now, join us as we kick off 2025 with a closer look at a few of the forthcoming titles that have already made it our way.

*

Mia S. Willis, the space between men

Penguin Books, January 14

the space between men, the resonant title of Mia S. Willis’s debut collection, might suggest spaces of safety and freedom, hard-won havens in a patriarchal South: “i was born under a north carolina wind bloated with acid / where women forge brave lacquered armor of constraint.” Or it might be the outer space of astronomy and astrology, of natural recurrences and utter oblivion, as in a partly blacked-out triptych of elegies “for retrograde & my sister brandi”: “uranus. / my capricorn and i don’t remember my sister’s face anymore. / when the sun sets on earth, it does not disappear from the sky.”

And in poem after poem, “the space between men” is some space within everyday and literary language for queer communities of Black bois and femmes. It’s a space Willis helps build with their spilling-over toolkit of poetic forms, including newly canonical African American forms like the kwansaba, the bop, and the eintou. And it’s a space Willis studies with a researcher’s remove and a linguist’s ear for sound and situation: “‘boy’ and ‘boi’ are homophones distinguishable only by their context. // ex. police officer to my father: where are you coming from, boy? // ex. lover’s hand to my cheek: where are you coming from, boi?” –CS

Reginald Dwayne Betts, Doggerel

W. W. Norton, March 4

“Doggerel,” according to any trustworthy dictionary, refers to verse that’s “comic, burlesque, and usually composed in irregular rhythm,” or (more derogatorily) “badly composed or expressed; trivial.” Reginald Dwayne Betts disagrees. On the very first page of his fifth collection Doggerel is a dictionary entry with the above-quoted phrases crossed-out, followed by Betts’s counter-definition: “nah, just a Black man writing poems about his dog, & all the dogs he encounters on the street, & how having an extra four feet changed his world, & then he falls in love.” Doggerel finds Betts honing familiar forms and modes—his ghazals, his redactions and rearrangements of found language, his meditations on prison and prison’s permanent restructuring of life outside it: “Tell me how these / Peonies have migrated from Asia to my garden, / Have found their way into my line of vision / Despite prison & all the suffering I don’t speak.”

And true to Betts’s word, Doggerel includes dozens of poems about Taylor (or Tay-Tay), “a small Jack Russell whose heart, / When resting, beats 50 times per minute,” and canine passers-by like that little dog “With a patch of brown over his left eye” who “looks like the kindest pirate / On this planet.” If Betts’s doggerel is a poetry of animal otherness—of the vulnerability, menace, and ardor held inside and provoked by dogs—it’s also a poetry of kinship across species, of feelings “familiar from one continent to another”: who, dog or human or otherwise, hasn’t had “that feeling, for / A moment, for at least a second, if that, to just fucking howl.” –CS

Mai Der Vang, Primordial

Graywolf Press, March 4

Three years ago, Mai Der Vang’s Yellow Rain, an expansive performance of documentary poetics grounded in the materiality of collaged archival documents, was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. She returns this March with a more contained third collection, Primordial, which also centers ongoing ramifications of the Vietnam war, and the submersion of truths, on Hmong people. Here, her focus turns to the saola, an elusive endangered animal sometimes referred to as the “asian unicorn” of Laos and Vietnam. Metaphor? Scientific evidence? Embodiment of the persistence of a people? The saola morphs in purpose and presence across these poems, as Mai Der Vang continues to forge an ecopoetics that embodies intricate intersections of war, colonialism, environment, and refuge. “Evolution/Absence” weaves statements such as “Hmong people exist/ I am a Hmong person who exists” and “The saola is a secret/ The saola exists.” These are poems of survival. –RMF

César Vallejo, The Eternal Dice: Selected Poems, translated from the Spanish by Margaret Jull Costa

New Directions, March 4

Among English-language readers, the Peruvian modernist poet César Vallejo (1892–1938) may be best known for writing “Piedra negra sobre una piedra blanca” (“Black Stone on a White Stone”), the twentieth century’s most imitated poem on the subject of one’s own death: “I’ll die in Paris in a shower of rain, / a day I already hold in my memory. / I’ll die in Paris—and I’m in no hurry— / perhaps on a Thursday, like today, in autumn.” (You can assemble an anthology of self-elegies written in Vallejo’s shadow, from W. S. Merwin’s “For the Anniversary of My Death” to Donald Justice’s “Variations on a Text by Vallejo” to A. B. Spellman’s “After Vallejo.”) That undying poem appears, alongside selections from across Vallejo’s brief yet fruitful career, in The Eternal Dice, newly translated by Margaret Jull Costa, who renders Vallejo’s provocations and paradoxes with deadpan clarity: “I was born on a day / when God was ill”; “My eternity died and here I am keeping vigil.” —CS

Esther Lin, Cold Thief Place

Alice James Books, March 11

Even if it were pure story, an autobiography narrated like any other, it’d be worth seeking out Cold Thief Place, Esther Lin’s first full-length collection. She was born in Rio de Janeiro to Chinese parents, her father sailing to Brazil by way of Africa, her mother getting married “to defect from China. / To a man already married.” Lin’s mother was assured she would give birth to a prophet—but “When the doctors said girl, she changed my name / from Samuel to Esther. Prophet to concubine.” A decade later, Lin’s mother was still choosing an apocalyptic Christianity over her daughter, now living in the United States as an undocumented immigrant: “she asked in the parking lot, / Is it better to be / citizens of Heaven / or of the United States?…And this is how my siblings and I / remained illegal.”

But the spinal cord of Cold Thief Place is not a singular life story but Lin’s nervy consciousness of how variously that story can be told and retold, recontextualized and generalized to philosophical and legal abstraction: “Illegal Immigration,” notes the poem by that title, “Is the absence of a paper / and the presence of a person.” Taken together, it’s a memoir anything but straightforward: Cold Thief Place amasses an argument against chronology, moving in a matter of lines from last memories of a mother “split by cancer” to a portrait of a young woman in 1974, “clasping the arm / of a married man, her wrapped hair / and secret smile.” –CS

Annie Wenstrup, The Museum of Unnatural Histories

Wesleyan, March 25

Dena’ina poet Annie Wenstrup’s innovative debut turns to the texts and contexts of museum exhibits, launching tone and style with an opening chart, “Event Score for the Curator,” prefaced by instructions that begin: “Make the most of your time at the Museum of Unnatural Histories by following along with the event score.” Labels appear throughout the book in different sizes and orientations. A “robotic docent” leads the speaker past Gaugin, past “Captain Cook’s sketches of Aleut women/ labeled savage.” Wenstrup collects snippets of poets—Natalie Diaz, Joan Naviyuk Kane—in neatly framed labels; dioramas; poems about Jon Benét Ramsey and Prince Diana; a script for a Lifetime movie; and stories: “You can find my Chada’s stories in places like this. / In museums, in libraries, on cassettes and online catalogues.” She reminds us, both in design and in narrative, of the troubling nature of documentation, not just painterly, but textual: “When Chada wrote Ggugguyni, the gurgle-breath / Raven names herself with, another translated/ it as crow. The translator meant crow while / I know what Chada meant. He meant Ggugguyn.” –RMF

Rachel Trousdale, Five-Paragraph Essay on the Body-Mind Problem

Wesleyan University Press, March 25

If the title of Rachel Trousdale’s Five-Paragraph Essay on the Body-Mind Problem sounds on the silly side for a poetry collection—really, you’re going to settle a bottomless philosophical predicament in formulaic high-school-paper fashion?—then reader, you’re in tremendous luck: Trousdale is one of our leading scholars of silliness and modern poetry alike, the editor of the essay collection Humor in Modern American Poetry (2018) and the author of Humor, Empathy, and Community in Twentieth-Century American Poetry (2021).

As even luckier readers gathered from her appearances in literary magazines and the chapbook Antiphonal Fugue for Marx Brothers, Elephant, and Slide Trombone (2015), Trousdale also writes full-bodied, encyclopedia-minded poems: Five-Paragraph Essay, the inaugural winner of Wesleyan University Press’s Cardinal Poetry Prize, is her long-awaited debut collection. Trousdale performs comedy virtuosically, in all its major and minor keys—observational humor, cartoonish incongruity, loving teasing, cerebral shade (she titles one poem “I Swear This Is Not Intended as a Back-Handed Compliment”). But she’s also a poet of marital and parental ardor, ethical focus, and condensed contemplation, as in “Collection,” a two-line poem deeper than many a five-paragraph essay: “A few stones at a time / my son brings home the mountain.” –CS

Chaun Ballard, Second Nature

BOA Editions, April 1

Chaun Ballard’s debut, Second Nature, the most recent A. Poulin, Jr. Poetry Prize winner from BOA, romps and resets through long titles like “Surely, I Am Able to Write Poems Celebrating Grass and How the Blue in the Sky Can Flow Green or Red–Poems about Nature and Landscape but Whenever I Begin the Trees Wave Their Knotted Branches” and “Ars Poetica or Self-Portrait Beginning with a Haiku before Shaking the Polaroid into Image and Keeping the Darkness for Ourselves,” as well as “Michael Brown as my father or Michael Brown as my Grandfather or Michael Brown as my Father and Grandfather or All Three as an Old Man.” This one just made it to my inbox, but I wanted to fit it in here: within Ballard’s formal play, including plenty of erasures, surge poems of intersecting lineages: familial, poetic, historical. The persona poems featuring the ghost of Johnnie Taylor are standouts. –RMF

Amy Gerstler, Is This My Final Form?

Penguin Poets, April 1

Spoiler alert: Gerstler’s newest collection features fish sex. Or at least attempted fish sex, involving sirens on an island at the center of the collection’s ten-minute play, “Siren Island.” Readers can expect irreverence, wit, and poems like “The Bible as Literature,” edged with Gerstler’s rhythms: “She clubbed her new husband to a pulp / with a fire extinguisher when she was young. /These things happen.” There’s the chugging of dinosaur urine—“No virus can slay you with dino piss in your system”—a Mae West Sonnet, the Egyptian Book of the Dead—“Is this the best choice of reading when I can’t sleep, a text/ crammed with fears of being eaten by animals/ of decapitation”—and a tone that feels just about right for heading into 2025. As “Wound Care Instructions” opens, “This is the inside-out of the sublime.” –RMF

Maggie Nelson, Pathemata, or, The Story of My Mouth

Wave Books, April 1

Do you want to know about Maggie Nelson’s jaw pain? The ostensible subject of this book might not grab you at first, but let’s face it, you either want to hang out in Nelson’s mind through daily chronicles and dreams and other wanderings, or not. She herself says, “Not long after I begin my experiment of looking at other people’s mouths, I quit it. It feels intrusive and mean, and also like bad karma, if I don’t want anyone looking at mine.” But as she carries us through the experiences of other people real and imagined (including her dream self) looking at her mouth, something starts to happen as much as nothing happens. There are dreams: abductions, “the pram in Plath’s apartment—white, upright, note attached.”

There’s remote school, Zoom events, more dentists. If you’re expecting Bluets, you’ll be disappointed. If you’re expecting The Argonauts, you’ll be disappointed. This unique work embodies its own definitions of hybridity responding to the conditions of its making—a pandemic, a history of mouth issues, a series of dentists, parenthood—as well as to Hervé Guibert’s The Mausoleum of Lovers. This is “an experiment in interiority written in the pandemic studio” book. This is a Wave book. Fans of Nelson will want Pathemata on their shelves. –RMF

Mary Helen Callier, When the Horses

Alice James Books, April 15

I fell for this debut collection two poems in. Callier’s crisp marriage of sentence and line sings across the psychic landscapes of childhood and into elements of desire made slant. “First Love” concludes: “The girl and I would play for hours, / fingers in each other’s mouths. Then, / she flipped a doll’s crib upside down/ and trapped me there. Said: You’re the dog now.” When the Horses simmers with violence and a strange and palpable imagery, delivering endings that twist their landings: “The swan bends its neck / the whole way back, and this is like falling in love.” This collection is full of surprises, with echoes of Gluck’s precision and Brigit Pegeen Kelly’s visceral imagination, but with Southern roots. (Callier is from Columbus, Georgia.) Midway through “My Body is a Lake,” “They found/ you, pale and wet/ as a newborn rat. / They slid their hands into your mouth, a horseless bit.” –RMF

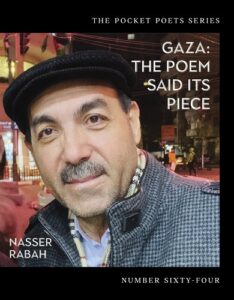

Nasser Rabah, Gaza: The Poem Said Its Piece

City Lights Publishers, April 15

“If I were to pick only one poet from Gaza to be translated and published in the English-speaking world, this is who it would be,” writes Mosab Abu Toha in his foreword to Gaza: The Poem Said Its Piece, a forthcoming selection from the Palestinian poet and novelist Nasser Rabah. Printing Rabah’s Arabic originals in parallel with English translations by Ammiel Alcalay, Emna Zghal, and Khaled al-Hilli, Gaza culls from three of Rabah’s collections and ends with poems written during Israel’s ongoing devastation of Gaza, where Rabah was born and still lives. (Rabah’s study and library, his translators note in an afterword, are now ruins; the first book Rabah pulled out from the rubble was War and Peace.)

Gaza’s final eight poems, dated from November 19, 2023, to April 12, 2024, witness atrocities reaching an indigestible regularity: “A day passes, and a day and a night, and / the neighbors’ son doesn’t wake up.” Amid the onslaught, Rabah’s poems retain their undiminished power to reach across time and space to address you, whether that “you” refers to his countrymen or himself, the newly dead or the still living, or even the auditor of the book’s final lines: “O Gaza, accursed, beloved, deranged, oppressed, outcast, / enchanted, forgotten, mentioned a thousand times / in the Book of War, you’re not the Goddess of the Dead, / nor is your book called Sorrow of the Country.” –CS

Jim Moore, Enter

Graywolf, May 6

You may have read Jim Moore’s memorable and moving poem “Mother” in The New Yorker this past year: it begins “My friend and I had a cat we called Mother,” and unfolds into the speaker’s revelation of surviving a rape, and of telling his “actual mother about the rape.” Poems such as this, and the pandemic-era preface poem, mark the sincerity prevalent in this eighth collection. Moore also weaves in another kind of intimacy of speaker, that embedded in acts of reading: where else might you find Tsvetaeva and an old man with a skateboard together in a poem? And looking: a poem after Caravaggio’s “The Entombment of Christ” is gorgeously precarious with Christ’s bodily weight and delicacy stamped by the observations of the viewer: “He has a mother” and “Death is so awkward.” Moore’s experienced touch is light and concise without minimizing the substance of his inquiries. –RMF

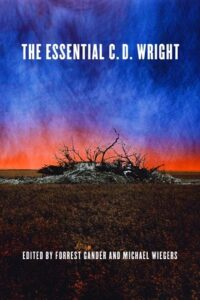

C. D. Wright, The Essential C. D. Wright, edited by Forrest Gander and Michael Wiegers

Copper Canyon Press, May 13

When the American poet C. D. Wright (1949–2016) died unexpectedly at the age of 67, she left behind grief-stricken audiences, cohorts of grateful students, and inheritors and imitators across several generations. And she left future readers with a problem that would be the envy of many poets: she had been too good, in too many modes, for too long. Wright wrote lines, even entire lyrics, so letter-perfect they tattoo themselves on the memory instantly: “Comrades, be not in mourning for your being / to express happiness and expel scorpions is the best job on earth.” But she also wrote plenty that remains hard to find, difficult to excerpt, or both: her first books, published by small, defunct presses; monumental documentary projects like One Big Self (2003/2007) and One With Others (2010); and unclassifiable mergers of poetry and prose, writing and photography.

Nine years after her death comes The Essential C. D. Wright, edited by her partner of 35 years, Forrest Gander, and her former editor at Copper Canyon Press, Michael Wiegers. It’s the best solution to date to the problem of Wright’s genius and abundance. Gander and Wiegers’s selections span five decades, ranging from unpublished early work, already flaunting Wright’s knack for winning titles (“Why Don’t You Go Sit Under a Big Tree”), to her last books, the posthumous publications ShallCross (2016) and Casting Deep Shade (2019). –CS