Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley was published on November 30, 1955, 63 years ago today. It is, in my opinion, the perfect winter holiday book. It’s acrobatic and addictive reading, the prose sharp-edged and wry and sometimes quite pretty, and also it’s about warm weather and beautiful people, at least one of whom is decidedly amoral but perplexingly sympathetic. This, of course, is Tom Ripley, a small-time con-man who stumbles into a new life—one he will literally kill to keep. You probably know Tom, even if it’s only because you’ve seen the movie. If you haven’t, go away and read the book, and then watch the movie, and then come back to this article on the internet (or not, because if you do the first two things my job will already be done).

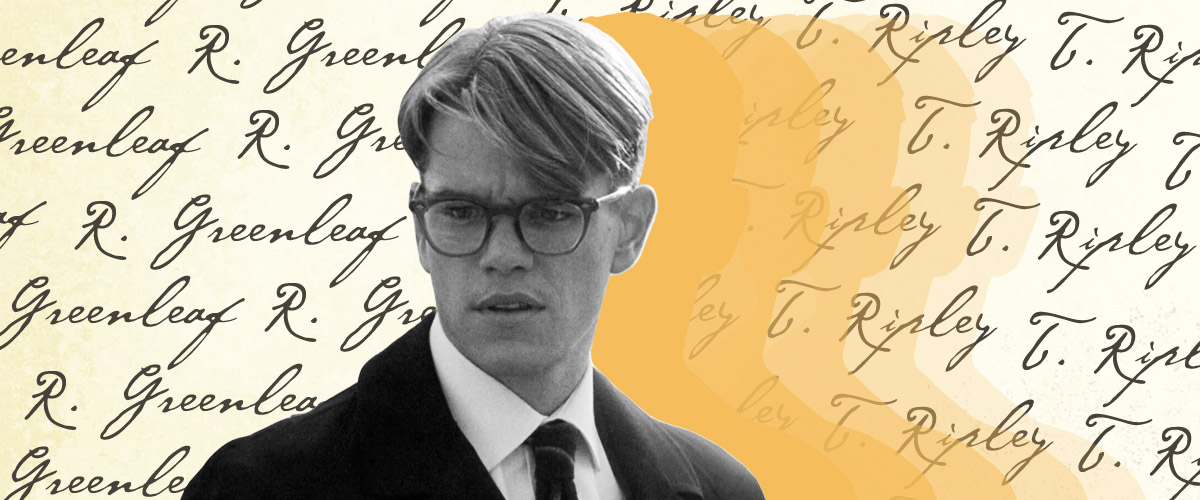

I’ve read The Talented Mr. Ripley a number of times, and with each reading I see it in a slightly different light—one reliable quality of good literature. This year, it felt more than anything like a coming of age story—it’s only that the person Tom Ripley comes of age into is someone other than himself. Of course, many novels feature character arcs, moral and psychological sea changes, evolutions and devolutions. But there is something particular about the coming of age novel, in which a young protagonist comes into his or her own, often through fire. They become, by the end, the person they were always meant to be. In Tom Ripley’s case, that person is Dickie Greenleaf.

But let’s look at the text—starting with the first paragraph, which is always the best place to start. We begin in New York City, with Tom’s paranoia:

Tom glanced behind him and saw the man coming out of the Green Cage, heading his way. Tom walked faster. There was no doubt the man was after him. Tom had noticed him five minutes ago, eyeing him carefully from a table, as if he weren’t quite sure, but almost. He had looked sure enough for Tom to down his drink in a hurry, pay and get out.

On a second reading (or even a first, depending), it’s impossible not to see the double entendre of Ripley’s anxiety here: he thinks he’s being followed by a detective, sure, but he also thinks he’s being followed by, as he calls it on the next page, dismissing it and entertaining it at the same time (after all he’s thinking it, we are told, for the second time): “a pervert.” This opening gesture radiates throughout the novel, and so too that sense of other people not being “quite sure, but almost,” though Tom’s homosexuality is not nearly as explicit as it is in the film adaptation. It is one of the elements of his original self that Tom would like to shake (though it is one that Highsmith subtly suggests he does not—not everything is mutable, after all).

In the early sections of the novel, Highsmith presents Tom as nervous and strange—we find him to be exactly how he fears people might find him. Yes, he has some affinity for people: he can read them, and he can get along, but the reader hears how nervous he is, how much it takes out of him. He is, as he reminds us, a nobody. Then there’s the relatively pathetic scam he’d been running—the one that made him think a detective might be after him—in which he impersonated an IRS officer and demanded payment from random strangers. He had not succeeded in taking anyone’s money—they made the checks out to the IRS, and he couldn’t cash them. But somehow Tom couldn’t stop contacting people, writing letters, talking to them on the phone—an early indication of his desire to be somebody, anybody, other than himself. Well, not anybody—someone with power. Someone with money.

As it turns out, the man who had been chasing Tom in the first paragraph was no cop or potential lover but Mr. Greenleaf, a rich gentleman who asks Tom to go over to Italy and convince his errant son to come back and join the family business. When Tom meets him and his wife for dinner, his nervousness is discomfiting—though as far as the reader knows, there’s really nothing to be nervous about. And yet:

In a large mirror on the wall he could see himself: the upright, self-respecting young man again. He looked quickly away. He was doing the right thing, behaving the right way. Yet he had a feeling of guilt. When he had said to Mr. Greenleaf just now. I’ll do everything I can . . . Well, he meant it. He wasn’t trying to fool anybody.

He felt himself beginning to sweat, and he tried to relax. What was he so worried about? He’d felt so well tonight! When he had said that about Aunt Dottie—

Tom straightened, glancing at the door, but the door had not opened. That had been the only time tonight when he had felt uncomfortable, unreal, the way he might have felt if he had been lying, yet it had been practically the only thing he had said that was true: My parents died when I was very small. I was raised by my aunt in Boston.

Tom wears his past uncomfortably, which means he wears his present uncomfortably too. He is afraid of water; his parents drowned in Boston Harbor. He feels he was mistreated by his Aunt Dottie, who repeatedly called him a “sissy,” who is rich enough to send him money but doesn’t, or rather sends him “piddling cheques for the strange sums of six dollars and forty-eight cents and twelve dollars and ninety-five, as if she had had a bit left over from her latest bill-paying, or taken something back to a store and had tossed the money to him, like a crumb . . . an insult.” He despises his youth, but also feels deeply connected to it—otherwise he wouldn’t have to push against it quite so fiercely. Later, on the boat to Europe, Ripley thinks back to his childhood:

It was like looking back at another person to remember himself [at thirteen], a skinny, snivelling wretch with an eternal cold in the nose, who had still managed to win a medal for courtesy, service, and reliability. Aunt Dottie had hated him when he had a cold; she used to take her handkerchief and nearly wrench his nose off, wiping it.

Tom writhed in his deck-chair as he thought of it, but he writhed elegantly, adjusting the crease of his trousers.

He writhed, but elegantly! Elegantly, while adjusting the crease of his trousers! Fastidious to a fault, our Tom. Elegance is his only recourse against his past, against what he secretly thinks of as his true self. Of course this is a novel largely about class—Tom hates vulgarity, inelegance, dirtiness. He is a poor orphan of no particular birth, and he is enamored of those who can live a life of leisure, in Europe, on their father’s coin. He hates the squalid apartment he has to live in, the ways he has to get by. He wishes (don’t we all) for the freedom and the privilege that money brings. He thinks he can get there, eventually. This is all to say that he has always wanted to grow up to be Dickie, even without knowing Dickie yet.

Then he does meet him, and he is instantly enchanted. His longing now has a specific direction: he is desperate to be Dickie. Look at this passage, a passage whose intensity I certainly missed on the first read, which takes place after the first encounter with Dickie and Marge on the beach. Tom finds their reception lukewarm, so he goes home, gets food poisoning, and tries again three days later. But the description of those three days is brilliant:

He actually had been too weak even to leave the hotel, but he had crawled around on the floor of his room, following the patches of sunlight that came through his windows, so that he wouldn’t look so white the next time he came down to the beach. And he had spent the remainder of his feeble strength studying an Italian conversation book that he had bought in the hotel lobby.

It flies by on the page as slightly comic—but stop and imagine someone actually doing this. Crawling around on the floor in between trips to the bathroom, just to look slightly less pale—slightly more like Dickie. It’s so pathetic, so childish, and so filled with desire. Not for the man he has at this point only met once, but for everything he represents.

Tom’s eventual transformation into Dickie runs parallel to his transformation into a murderer. The Tom we meet in New York couldn’t really murder anyone—sure, he fantasizes about stabbing old Aunt Dottie to death with her brooch pin, but it’s clear at the beginning that he doesn’t have it in him. It’s only when he actually puts on Dickie’s suit that the fantasies become a little more convincing.

“Marge, you must understand that I don’t love you,” Tom said into the mirror in Dickie’s voice, with Dickie’s higher pitch on the emphasized words, with the little growl in his throat at the end of the phrase that could be pleasant or unpleasant, intimate or cool, according to Dickie’s mood. “Marge, stop it!” Tom turned suddenly and made a grab in the air as if he were seizing Marge’s throat. He shook her, twisted her, while she sank lower and lower, until at last he left her, limp, on the floor. He was panting. He wiped his forehead the way Dickie did, reached for a handkerchief and, not finding any, got one from Dickie’s top drawer, then resumed in front of the mirror. Even his parted lips looked like Dickie’s lips when he was out of breath from swimming, drawn down a little from his lower teeth. “You know why I had to do that,” he said, still breathlessly, addressing Marge, though he watched himself in the mirror. “You were interfering between Tom and me—No, not that! But there is a bond between us!”

What’s striking to me here is Tom’s sudden possessiveness over Dickie, and his obvious pleasure in seeing himself as Dickie, returning to the mirror, playacting for himself. I thought of a little girl dressing up in her mother’s clothes, imagining that she’s a woman. When the fantasy isn’t perfect—there’s no handkerchief in the pocket—he adjusts to make the reality fit his vision. He protests again that his obsession with Dickie isn’t romantic, which of course only solidifies for the reader that it is.

Soon after this, Dickie is dead. In my memory, which has perhaps been infected by the film, Tom kills Dickie in a moment of passion, in a way that could happen to anyone, or anyone with a certain set of proclivities at least—it was a mistake, an angry reaction, while being mocked and threatened, so that everything that happened after was just an instinct for self-preservation taken too far. This is the root of many stories: present a normal person with an outrageous problem, and see what kind of knots they twist themselves into to escape it. But Tom is not a normal person. My memory was wrong: in the book, he plans to murder Dickie, almost offhandedly, an idea on the train, and then a few pages later, he just does it. There is no handwringing. There is no remorse.

This, of course, is the turning point in the novel. The rest of it concerns Tom’s elegant writhing—away from the cops, into his new life—and his full transformation into Dickie. At first, it’s just a way to get money—signing Dickie’s name on his monthly checks, selling his boat and furniture—but soon Tom begins to love being Dickie in particular. He doesn’t want to be a rich version of Tom. He likes being Dickie better—after all, Dickie is confident, respected, independently wealthy, earnest and yes, elegant. He is what an adult man should be like. When Tom goes to Paris as Dickie, fully adopting his persona, he starts to feel like he has entered the world as he should be.

Tom felt completely comfortable, as he had never felt before at any party that he could remember. He behaved as he had always wanted to behave at a party. This was the clean slate he had thought about on the boat coming over from America. This was the real annihilation of his past and of himself, Tom Ripley, who was made up of that past, and his rebirth as a completely new person.

He leaves the party and stops at a bar-tabac, where he orders “a ham sandwich on long crust bread and a glass of hot milk, because a man next to him at the counter was drinking hot milk. The milk was almost tasteless, pure and chastening, as Tom imagined a wafer tasted in church.” This is his first communion as Dickie Greenleaf.

Soon thereafter, the artifice fades away. He is no longer Tom Ripley impersonating Dickie Greenleaf. He inhabits him fully—in the terms of my premise here, he grows into him:

It gave his existence a peculiar, delicious atmosphere of purity, like that, Tom thought, which a fine actor probably feels when he plays an important role on a stage with the conviction that the role he is playing could not be played better by anyone else. he was himself and yet not himself. He felt blameless and free, despite the fact that he consciously controlled every move he made. But he no longer felt tired after several hours of it, as he had at first. Now, from the moment when he got out of bed and went to brush his teeth, he was Dickie, brushing his teeth with his right elbow jutted out, Dickie rotating the eggshell on his spoon for the last bite. Dickie invariably putting back the first tie he pulled off the rack and selecting a second. He had even produced a painting in Dickie’s manner.

Imitate the people you admire, we tell adolescents, and soon you’ll grow into your own person. Now, Tom has grown up, and he’s delighted about it. In fact, when he is obliged to become Tom again, it feels like a true loss, a regression:

He hated becoming Thomas Ripley again, hated being nobody, hated putting on his old set of habits again, and feeling that people looked down on him and were bored with him unless he put on an act for them like a clown, feeling incompetent and incapable of doing anything with himself except entertaining people for minutes at a time. He hated going back to himself as he would have hated putting on a shabby suit of clothes, a grease-spotted, unpressed suit of clothes that had not been very good even when it was new. His tears fell on Dickie’s blue-and-white-striped shirt that lay uppermost in the suitcase, starched and clean and still as new-looking as when he had first taken it out of Dickie’s drawer in Mongibello.

Even more interesting than his real despair—I think these are the only tears he sheds in this novel, which has two murders in it, one of someone he was probably in love with—is that once he is Tom Ripley again, he actually has to act the part. Tom has become the false face. “He began to feel happy even in his dreary role as Thomas Ripley,” Highsmith writes. “He took a pleasure in it, overdoing almost the old Tom Riley reticence with strangers, the inferiority in every duck of his head and wistful, sidelong glance.”

This is not a novel about one man impersonating another. It’s about one man becoming another—the man he always hoped to be. The fact that he had to kill someone else to make space for himself in that role is just what makes it fun.

By the end of the book, Tom has fully evolved: he is even over the bad childhood that seems to be the originating kernel of all of his discontent.

There was a sureness in his taste now that he had not felt in Rome, and that his Rome apartment had not hinted at. He felt surer of himself now in every way.

His self-confidence had even inspired him to write to Aunt Dottie in a calm, affectionate and forbearing tone that he had never wanted to use before, or had never before been able to use. He had inquired about her flamboyant health, about her little circle of vicious friends in Boston, and had explained to her why he liked Europe and intended to live here for a while, explained so eloquently that he had copied that section of his letter and put it into his desk.

He felt surer of himself in every way—is that not the most emblematic marker of entering into adulthood? But even with all his new self-confidence, not everything has changed. That first paragraph is echoed in the last moment of the novel, in which Tom gets off the boat in Greece, fully expecting to be arrested, even imagining that he sees four policeman waiting for him on the dock. But they are not policemen, or at least they are not there for him, and he goes past them. His freedom assured, he imagines Crete:

He saw four motionless figures standing on the imaginary pier, the figures of Cretan policeman waiting for him, patiently waiting with folded arms. He grew suddenly tense, and his vision vanished. Was he going to see policemen waiting for him on every pier that he ever approached? In Alexandria? Istanbul? Bombay? Rio? No use thinking about that. He pulled his shoulders back. No use spoiling his trip worrying about imaginary policemen. Even if there were policemen on the pier, it wouldn’t necessarily mean—

“A donda, a donda?” the taxi driver was saying, trying to speak Italian for him.

“To a hotel, please,” Tom said. “Il meglio albergo. Il meglio, il meglio!”

The best hotel, he tells the driver. The best, the best! Well, after all, it is what Dickie would say.