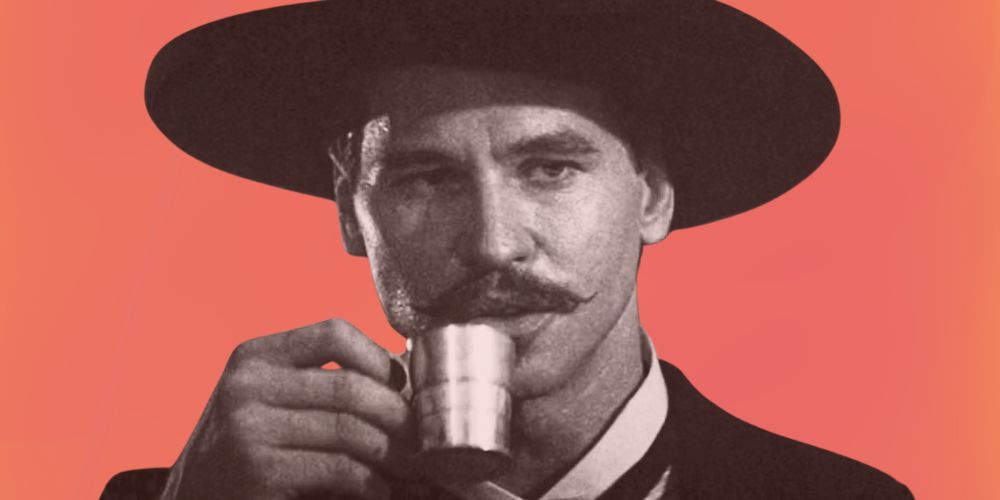

A Close Reading of the Poetry of Val Kilmer

Nick Ripatrazone Revisits the Work of a Wounded Heart

In 1977, Val Kilmer was 17. He was “raw with grief” over the recent death of his younger brother, Wesley. He flung himself into his studies at Juilliard, where he’d auditioned for the drama program with a poem.

“I wrote my own piece because I couldn’t find anything that would be fresh,” he said. “They’d heard everything and I knew that, so I decided to do my own thing and see how it went.” His own thing was “Sand,” an original poem:

Sand. It is poured in my side

and when it is still and it is night

and ground on even lines rests in sleep.

At the time, Kilmer was the youngest actor to be admitted into Juilliard’s program. Poetry got him there; it could be no other way.

In second grade, he read a poem aloud to his class: “Trees,” by Joyce Kilmer, his second-cousin, twice-removed. The penultimate line: “Poems are made by fools like me.” The young Kilmer loved words. “I was thrilled by how love rhymed with dove and semi-rhymed with hug.”

Verse wasn’t merely a youthful hobby. Kilmer continued to write, and read, widely. He loved Seamus Heaney. “To me he is the best kind of poet. He is a real dreamer,” Kilmer said. Heaney had “that Irish predilection for darkness—yet still holds on to that joy of life.”

In 1987, Kilmer self-published My Edens After Burns, a collection of poems, which infamously contains a piece titled “The Pfeiffer Howls at the Moon.” Kilmer and Michelle Pfeiffer met while filming an ABC Afterschool Special, “One Too Many,” and the poem was originally written to be given to her.

Kilmer wrote poetry between filming scenes of Thunderheart. A perfectionist—to the point of obsession—Kilmer said that poetry “helps” to calm his mood: “I don’t have to please anyone but myself.”

His most comprehensive volume was Cowboy Poet Outlaw Madman: Selected Poems, 1987-2020. Many of the poems are rollicking, playful. In “Rock Hounds in Love,” a shriner’s wife thinks about “when she was a waitress / in Nashville” and “could have made Waylon one night” but didn’t: “God talked to her, right out an ice tea.”

Yet Kilmer also knew solemnity. In “For When I’ve Been Believed,” he begins with oblique lines:

See the humility of a once drunken holy

Technology is a fib or bridge to keep us content

To breathe in between reality

That opening stanza feels like an appendage of another poem. But the second stanza is moving; a man in love tells a woman “he digs her before she is ready to hear it.” The poem gently eases, then, to second person: “You cannot live without her.” And then deeper, to a parenthetical: “(I cannot, still, live without her.)”

For all his infamous brashness, Kilmer was a wounded soul, longing to be with Wesley again, convinced that reunion (and perhaps resurrection) was possible. He continues the poem with lines that carry the cadence of late Franz Wright:

She is eternity

Beneath the mask of blasphemy

See her near, meet her here

“What a marvel, a gorgeous girl,” he wonders, “Could one ever be conceived,” before ending:

For the times

When I’ve been believed

The final enjambed line hangs like a lament. “Onstage,” Kilmer once wrote, “I felt at home and also not at home.” A character who he portrayed “went through me, and therefore was me.” Each persona he portrayed “inevitably contained elements of myself.” Poetry, for Kilmer, was a proving ground of language, a place where his eccentricities could lay bare.

Kilmer, perhaps, wrote his own elegy in 1982, the year after he graduated from Juilliard. “We’ve Just Met But Marry Me Please” is a litany of jaunty questions:

Will you be my gal?

Will you shine that big roller coaster up into the sky?

Will you give me grown-up feelings?

Will you kiss my eyes?

Yet the poem’s narrator soon turns from playful to ponderous. The first stanza ends with a question: “And / Will you bury me?”

It is easy for that serious question to be lost among Kilmer’s characteristic smirks. Yet he remains in that deep emotion for the entire final stanza, an elegiac conclusion that captures how the late actor lived on the edge of comedy and tragedy—with his foot ultimately in the direction of blessed melancholy:

Bury me?

Bury me?

Bury me?

Bury me when I die?

Nick Ripatrazone

Nick Ripatrazone is the culture editor at Image Journal, and a regular contributor to Lit Hub. He has written for Rolling Stone, Slate, GQ, The Atlantic, The Paris Review, and Esquire. His most recent book is The Habit of Poetry (2023). He lives in New Jersey with his wife and twin daughters.