A close reading of a great American poem: Robert Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays.”

Every now and then literary Twitter remembers just how much of a genius Robert Hayden was and pauses in awe of his poem “Those Winter Sundays.” Hayden, who was born this day, August 4th, in 1913, had a marvelous body of work and was justly lauded as the country’s first Black Poet Laureate.* But it is the aforementioned poem—a clear-eyed but tender elegy to his foster-father—that people return to again and again; and it’s not hard to understand why:

Sundays too my father got up early

and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold,

then with cracked hands that ached

from labor in the weekday weather made

banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him.

The first sentence is one long nostalgic exhalation, its faint rhythms hidden in the line-breaks that lead us from cold and darkness to light and heat. And if this first sentence locates us immediately and resonantly in a place and a time, the second sentence, brief as it is, reveals everything we need to know about the poem’s main character.

I’d wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he’d call,

and slowly I would rise and dress,

fearing the chronic angers of that house,

As the speaker of the poem surfaces through the second stanza a tension rises with him, culminating in the poem’s pivotal line: “fearing the chronic angers of that house.” It is this note of discord, this complication, that invites the possibility of resolution, that sets up an ending that elevates the poem from nostalgic vignette to the highest form of elegy.

Speaking indifferently to him,

who had driven out the cold

and polished my good shoes as well.

What did I know, what did I know

of love’s austere and lonely offices?

Ah, the useless wisdom of hindsight: what words could we have said, should have said, to those who loved us in ways we could not possibly have understood at the time? This is a universal pain, a species of regret each of us must encounter eventually in life—and nowhere in the English language is it more beautifully expressed then in the last two lines of this poem, which I will repeat here, for good measure:

What did I know, what did I know

of love’s austere and lonely offices?

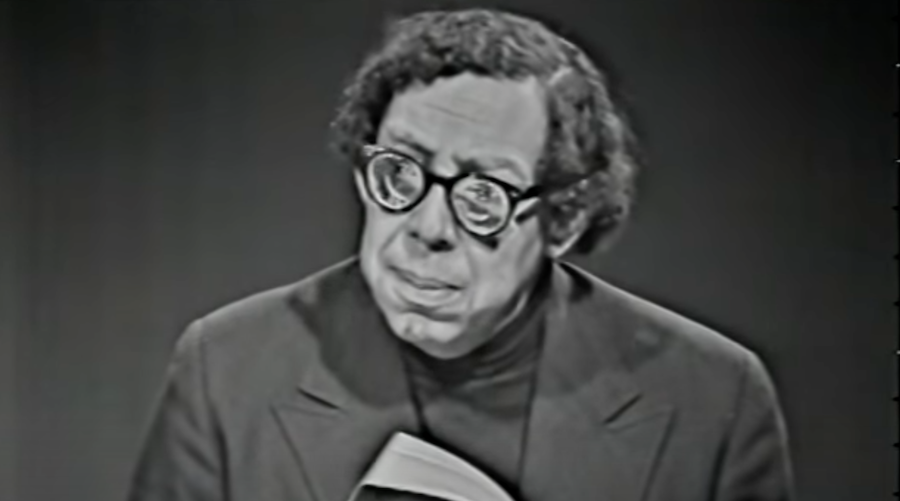

In looking for a recording of Hayden reading this poem aloud I came across the following interview at the 1976 Brockport Writers Forum, which is definitely worth 15 minutes of your life.

It begins with Hayden introducing his reading of “Those Winter Sundays” with a little context:

It was written for my foster-father who who made it possible for me to go to college and all the rest of it, who was a hardworking man, a Baptist… […] He cared a great deal for me and when the other boys would have to go out in the summers and work, he would help me to stay in school, and I owe him a great deal… He really cared about me getting an education; he used to say to me, “Get something in your head and you won’t have to live like this.”

There is a very tender pause after the last line of the poem, at which point Hayden says: “What hurts is that he never lived to know that I cared that much.”

[NB The interviewer in this clip, who smokes throughout, is a virtuosic embodiment of central casting middle-age beatnik, and is a thing to behold.]

*If you want to get technical, back in 1976 the position was called “Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress.” Don’t get technical, c’mon.

Jonny Diamond

Jonny Diamond is the Editor in Chief of Literary Hub. He lives in the foothills of the Catskill Mountains with his wife and two sons, and is currently writing a cultural history of the axe for W.W. Norton. @JonnyDiamond, JonnyDiamond.me