A Brief Survey of Famous Authors and Their Favorite Cocktails (and Colognes!)

Timothy Schaffert Considers the Fitzgeralds, Truman Capote, Josephine Baker, and More

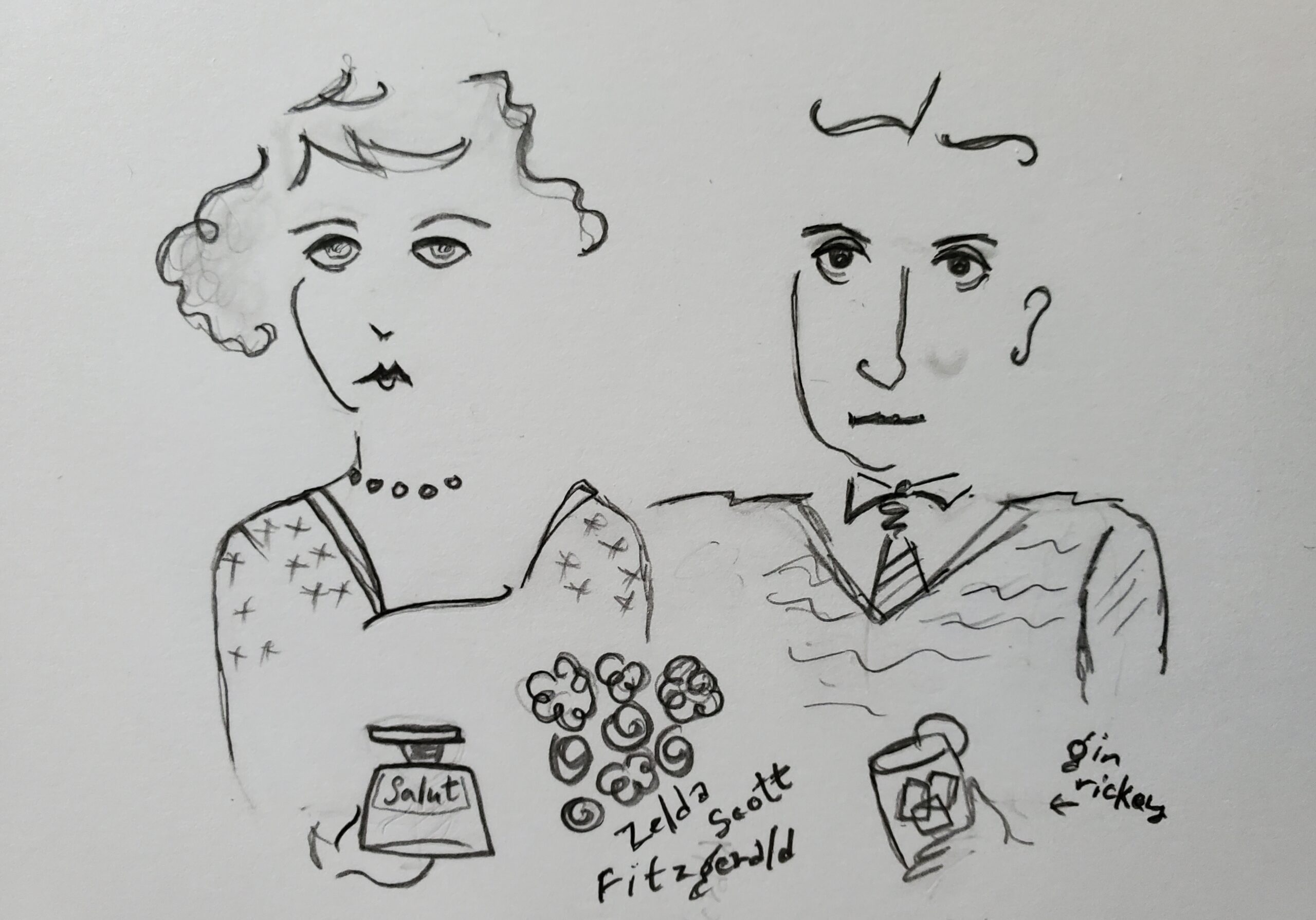

To write my novel The Perfume Thief, I spent a few years researching the cultural and political currency of perfume and fashion during WWII, and the role that luxury plays in perceptions of conquest and defeat. I also pondered what perfumes a perfume thief might thieve, leading me deep into the thickets of the archives of Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and Vanity Fair. I’ve always been captivated by the character of those magazines of the first half of the 20th century, a sensibility shaped by fashion illustration and celebrity caricature, work by Miguel Covarrubias, Julio Málaga Grenet, Helen Dryden, and other greats who gracefully marry cartoon, portraiture, and text.

The Perfume Thief is also about the other intoxicants of Paris: cognac, champagne, and cocktails. Perfume and liquor share parallels beyond just liquid and vapor (and alcohol); they convey personality and style. Our chosen fragrance, and our drink of choice, communicate something about our inclinations toward indulgence. Many don’t select a perfume only for its scent, and many don’t order a cocktail just for its buzz.

Taking these things into consideration has resulted in a side project, “Cocktails & Colognes,” a collection of my own illustrations and my notes on literary, intellectual, and cultural figures and the references to liquor and perfume (and glamour vs. intoxication) in their writing and biographies.

*

Zelda & F. Scott Fitzgerald

Salut de Schiaparelli; parfum

Zelda Fitzgerald, the author, painter, and prototype flapper, spent much of the 1930s in and out of psychiatric facilities; while she convalesced, her husband Scott travelled without her and worked in Hollywood as a studio hack. The Fitzgeralds madly swapped letters that carefully articulated all the particular strains of their charmed lives. And in these letters, they contemplated their tonics: for Zelda, it was beauty and perfume; for Scott, writing and gin (but never at the same time: “My work is done on coffee, coffee, and more coffee, never on alcohol,” he wrote in a letter in 1930).

With Scott in California, Zelda nudged him toward the border for bottles of Babani or Rosine: “either is cheap in Mexico.” When he sent her a bottle of contraband Salut, she proclaimed it “such amazingly adequate, and so sensorily gratifying a perfume that I wanted more of it.”

Zelda once told a newspaper that “having things, objects make a woman happy. The right kind of perfume, the smart pair of shoes. They are great comforts to the feminine soul.”

But in her fiction, perfume is less comfort and soul than it is a signal of social climbing. In her novel, Save Me the Waltz, her characters sit in a porch swing and attempt to delineate the fragrances of the garden … honeysuckle, star jasmine, cut hay… “‘It’s my perfume,’ said Alabama impatiently, ‘and it cost six dollars an ounce.’” In her short story, “Poor Working Girl,” the title character considers “all the refinement to be bought with seventy-five dollars: twenty-five dollar dresses and the ten-dollar perfume.” In another, “The Original Follies Girl,” a character “reeked of a lemony perfume and Bacardi cocktails.”

Gin Rickey

(gin, lime juice, club soda)

The most famous gin rickeys in all of literary history are those served by Tom in The Great Gatsby, cocktails that “clicked full of ice.” Gatsby remarks, with “visible tension” that the gin rickeys look cool, though he’s losing all cool of his own. Nick, the narrator, notes that “we drank in long, greedy swallows.”

Scott’s defenses of his drinking, in contradictory and meandering letters to Zelda, friends, and doctors, are long, greedy swallows themselves. (In a letter to Ernest Hemingway, he mentions that he’s either crying or his eyes are leaking gin.) He has his cake and eats it too, blaming Zelda for his decline even as he denies any decline at all. In a letter to a psychiatrist who had dared to suggest that Scott’s drinking contributed to his marital problems, he scolds the doctor for falling victim to Zelda’s joie de vivre. He boasts, with a conviction that must have sounded feeble even to himself, “during the last six days I have drunk altogether slightly less than a quart and a half of weak gin, at wide intervals.”

He’s a bit more self-aware in a letter to Zelda when he writes that those around them “guessed at your almost megalomaniacal selfishness and my insane indulgence in drink.” He signs off with a line that’s both admonition and forgiveness: “We ruined ourselves—I have honestly never thought that we ruined each other.”

Josephine Baker & Ada “Bricktop” Smith

SCENT

Arpège, by Lanvin

After working up a sweat frolicking topless on stage, Josephine Baker, the icon of 1920s Paris, would retreat to her dressing room to douse herself in flower juice. Her signature scent was more like an autograph book, with any number of perfumers insisting she’d singled out their own fragrances as her favorite: Guerlain’s Sous Le Vent; J.F. Schwarzlose Berlin’s Treffpunkt 8 Uhr; Jean Patou’s Joy; E. Coudray’s Tulipe Noire. It was titillating to be so intimately associated with her nakedness. “I have had rains of perfume on my body,” she once told Alexandre, the hairdresser who did-up her wigs.

Baker was so enamored of Lanvin’s Arpège, she devoted a room to it in her castle in Southern France – her bathroom was modeled in black tiles and gold fixtures, as if she sought to linger on the inside of the black-and-gold bottle itself. She would eventually be evicted from the property after years of a lavish generosity that included taking in orphans and donating her designer originals to drag queens. Flat-broke and retired from showbiz, she was famously photographed on the chateau’s front stoop, waiting to be escorted away by police. “If I die tonight, I want to be buried in the pink nightgown of my agony,” she told those who’d gathered. (Today, the home she lost is a tourist attraction devoted to her, and you can get a peek at her Arpège-ian loo.)

COCKTAIL

Rémy Martin champagne cognac

Baker’s memoirs (she published her first one at the age of 21) catalogue the gifts she received in her heyday: furs, jewelry, big peaches, perfume in a glass horse. On the other side of the saloon, and of an opposite sensibility, was club owner Ada “Bricktop” Smith; like Baker, she was an African American expatriate who fled to the jazz scene of Paris in the Twenties. Unlike Baker, she was down-to-earth and approachable, with a folksy demeanor. Bricktop’s memoirs were also quite opposite, her reminiscences given the soft glow of discretion and restraint, composed in old age. “I wouldn’t betray the memory of a friend or someone who was nice to me,” she wrote, to the frustration of those critics longing for gossip about the artists, writers, and aristocrats who got their champagne corks popped at her cabaret.

She also blamed cognac for her minimalism. “Looking back,” she wrote, “I know that a lot went on, but I really can’t remember specifics. I probably would have seen more if I didn’t like Rémy Martin so much.” The Rémy, and its fuzzying effects, might also be why she doesn’t describe her love affair with Baker; or perhaps she doesn’t write of the affair because there wasn’t one. The only evidence of Bricktop’s queerness (which she generally denied: “I never liked women… I was never big on the orgies that some people had”) is a parenthetical comment in The Hungry Heart, a biography of Baker written by one of the orphans she mothered. The rumors of Josephine’s affair with Bricktop were true, Jean-Claude Baker wrote in his dishy portrait of Josephine, “Bricktop told me so herself.” (The Hungry Heart was published 17 years after Bricktop’s death.)

Bricktop might have skipped the orgies, but she never gave up on the Rémy. An article in the San Francisco Examiner, “Bricktop at 65,” described her holding a small cigar in one hand and a glass of Rémy in the other. “People who say I’m a whisky drinking old woman are wrong,” she said. “I drink cognac.” Nearly 20 years later, she was nipping at some Rémy at her 82nd birthday party. “The doctors told her no booze,” wrote a Chicago Tribune society columnist, “but no one ever tells her what to do.”

Truman Capote & Carson McCullers

SCENT

Mitsouko eau de parfum, by Guerlain

Donald Windham, in his book Lost Friendships: A Memoir of Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams, and Others, described an evening stroll, “for which Truman doused himself in Mitsouko, tied a Bronzini scarf around his neck and draped his jacket over his shoulders.”

While Capote himself wore one of Guerlain’s most exquisite scents, his characters were most often perfumed in vulgarity, their affection for cheap fragrance a sign of their simplicity or naïve arrogance. In his short story “A Tree of Night,” a character “wore a frayed blue serge suit, and he had anointed himself with a cheap, vile perfume. Around his wrist was strapped a Mickey Mouse watch.” Similarly smelling is a woman in “Shut a Final Door” who, “reeking with dime-store perfume,” wore “only a sleazy flesh-colored kimono.” A woman in his story “Mojave” shares Capote’s taste for Mitsouko, but she “drenched herself in nose-boggling amounts” of it.

A prisoner in “A Diamond Guitar” (1950) keeps his “treasures” in a green silk scarf: a rosary, a pocket mirror, a map of the world, and a bottle of Evening in Paris cologne. Some twenty years later, Capote would begin a series of interviews with true-to-life prisoners, including Manson-family cult member Robert Beausoleil. Capote notoriously eschewed note-taking and tape-recording, and Beausoleil dismissed Capote’s published piece as mostly fiction. And, certainly, Beausoleil sounds like a Capote character, and perfume is again a metaphor for tastelessness, to a deadly degree: Beausoleil describes a vision of San Quentin’s gas chamber as a little igloo with windows for witnesses to “see the guys choking to death on that peach perfume.”

COCKTAIL

Whiskey Highball

(whiskey, soda, ice)

“Carson was seated in the living room, of course sipping, as tho’ it were sugar water, a whiskey highball.” This is an observation by composer David Diamond, the third in a romantic triangle with Carson and her husband Reeves. (David is curiously left out of the autobiography she was writing at the time of her death.)

While Scott Fitzgerald never drank booze at his typewriter, Carson McCullers drank nothing but, though she did often have tea with her sherry. Carson’s first biographer, Virginia Spencer Carr, paints one particularly vivid portrait that could serve any number of romantic delusions about liquor and literary fame: “…she sat hunched over her typewriter wearing a sweater and leather jacket, drinking scalding sherry tea and an occasional double shot of whiskey.” Elsewhere in the book, she’s on one end of a dining room table with her typewriter, Tennessee Williams on the other end with his, a whiskey bottle between them.

Even when she would return to her desk in the morning after a late night of whiskey and writing, she’d sober up with beer. Her drunkenness and personal turmoil, which seems likely sparked by her sexuality and that of her husband Reeve, inevitably fueled the psychologies of her characters. As Carlos L. Dews, the editor of her unfinished memoir, Illumination and Night Glare, notes: Carson’s relationship with Reeve and David was “instrumental in the development of her philosophy of loneliness and love, which is the most important theme in her fiction.”

Though McCullers didn’t speak directly to her sexuality in her memoir, her queerness and addiction were certainly wrapped up in a work of fiction she was writing at the time of her death. Exquisite Psycho was sometimes a novel, sometimes a play (her archives at the Harry Ransom Center list it as a “story” but with a question mark in parentheses), and it’s about an addict “of indeterminate sexual proclivity,” according to John Dalmas, a staff writer for the Journal News of White Plains, New York. While Carson’s biographer was denied permission to quote from the unpublished manuscripts, Dalmas had no such restrictions, and he published a scene from The Exquisite Psycho depicting two characters contemplating sexuality. “I wonder if that’s my real problem,” says a character named Camille. “Wonder whether I am bisexual. If that’s true it might solve a lot of problems.”

Greta Garbo & Mercedes de Acosta

SCENT

Valentina’s My Own

(Cologne water by designer Valentina,compounded by Caswell-Massey)

In 2017, twenty-seven years after Garbo’s death, her family finally sold her famous Manhattan apartment at 450 E. 52nd St (listed at $5.95 million, cash only), the joint still decked-out in Garbo’s bordello-esque pink-and-green color scheme and the bedroom walls still lined in Fortuny silk. Garbo’s personal effects were snatched up piece by piece in a multi-million-dollar auction that included paintings by Renoir and her cancelled checks to the electric company.

But my auction paddle would have swatted at the navy-blue redingote from Garbo’s closet. Wearing that coat, I’d hope to feel the chill of the years of prickliness between Garbo and the coat’s designer, Valentina. The two began as close friends in 1939, hitting it off after Garbo visited Valentina’s studio for a fitting; Valentina’s husband, George Schlee, stumbled in, getting a good eyeful of Garbo naked. This meet-cute seemed to set the tone for years of companionship, as the three went everywhere together. Valentina and Garbo even dressed alike for their nights out. By many accounts (and by the telltale fact that Garbo was alone with Schlee in Paris when he dropped dead from a heart attack), Garbo and Schlee were lovers; Garbo and Valentina might have been too. Even as early as 1946, Hedda Hopper spoke frankly, albeit coyly, in her gossip column: “I don’t believe those rumors that Greta Garbo and Valentina’s husband will ever wed even if there should be a divorce in that family.”

Like Garbo, the Schlees lived at 450 E. 52nd St, with Garbo’s same floorplan, and her same view of the East River. But with Schlee’s death in 1964, Garbo and Valentina became unneighborly, their doorman ever-alert to assure they never rode the elevator together. They did this dance of avoidance for twenty-five years after George’s death, until they themselves died within months of each other.

The Garbo auction included some half-empty bottles of perfume: Mitsouko, Miss Dior, Bois des Iles by Chanel (the lot of which went for a steal: $448). But according to promotional copy from the fragrance company Caswell-Massey in 1991, Garbo’s preferred scent was Valentina’s My Own, named for the designer but commissioned by George Schlee in 1950. It’s been out of production for decades, but it’s hard to imagine a more tantalizingly illicit scent from an American perfumier. How much would you pay at auction to snuffle at Garbo’s throat, breathing in the cologne named for her lover’s wife?

COCKTAIL

Mercedes Martini

Ingredients

-A goodly amount of Swedish vodka. [On the verge of poverty and needing cash, former socialite, poet/screenwriter, and lesbian/vamp Mercedes de Acosta published a tell-all that told little in 1960, but did include discreet snapshots of Garbo sunning herself topless on a vacation they had together in Silver Lake, Nevada in the 1930s. Garbo fumed, so Mercedes sent to Garbo a Christmas package of mistletoe, toys, and a bottle of vodka. Garbo kept the vodka and returned everything else without a note of thanks.] [Note: Garbo so loved vodka, her nephew challenged her will upon her death, claiming that Garbo’s brain was so befuddled by the hooch, she forgot to include him among her heirs.]

-A splash of Valentian vermouth bianco [In the 1920s, Mercedes swanned among the Manhattan elite, and introduced Valentina and George Schlee to society. Mercedes was in an open marriage with the painter Abram Poole, and she arranged for Poole to paint Valentina’s portrait. (The painting was up for auction as recently as 2017, where it sold for $11,000.) She wrote in her memoir that Valentina “had thick golden hair that trailed the floor when she loosened it.”]

-A dribble of orange bitters [Garbo devoted telegrams and letter after letter to de Acosta, over several years, dismissing her as bothersome. Garbo, ever-so ungently, encouraged de Acosta, again and again, to be content with what little affection Garbo gave her.]

-lavender-infused simple syrup [In 2000, Mercedes de Acosta’s Garbo archive, a collection documenting de Acosta’s decades-long infatuation with the movie star, sold at Christie’s for $23,500. The shrine included a whole scrapbook of those topless snapshots from Nevada, and an unproduced script Mercedes wrote for MGM with Garbo in mind to play Joan of Arc. But the most valuable item in this Garbo nymphaeum has to have been the notebook of love poems that Mercedes spent more than a decade composing for Garbo, all in lavender ink.]

__________________________________

The Perfume Thief by Timothy Schaffert is available now from Doubleday Books.

Timothy Schaffert

Timothy Schaffert is the author of five previous novels: The Swan Gondola, The Coffins of Little Hope, Devils in the Sugar Shop, The Singing and Dancing Daughters of God, and The Phantom Limbs of the Rollow Sisters. He is a professor of English and Director of Creative Writing at University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and he writes the column The Eccentricities of Gentlemen for the popular lifestyle magazine Enchanted Living. His latest book, The Perfume Thief, is now available.