A Brief Oral History of Rakim and the Golden Age of Hip-Hop

Jonathan Abrams on Lyricism and Mixing In Your Own Story

The success of Run-DMC and Def Jam, which proved hip-hop’s gargantuan commercial viability, would usher in what is now known as the golden age, during which a wave of innovation, competition, and diversity swept across the genre. The music’s pioneers, having established hip-hop, had left a canvas for another generation to take it wherever their imagination landed, and to master its capabilities and influence. While New York remained hip-hop’s heartbeat and epicenter, the genre started spreading outside the boroughs as Philadelphia artists like Schoolly D and West Coast artists like Ice-T and N.W.A gained a following.

During this period, wordsmiths like Rakim, Big Daddy Kane, Slick Rick, KRS-One, and Kool G Rap elevated the artistry of lyricism. Artists such as MC Lyte, Queen Latifah, and Salt-N-Pepa broke down doors for female artists. Producers influenced by Marley Marl, like Pete Rock and Gang Starr’s DJ Premier, began establishing New York’s sonic template. And the Native Tongues provided a bohemian alternative.

The divisive policies of the Reagan administration, and the havoc that the crack epidemic wreaked on urban communities, served as much of the golden age’s backdrop. The gap between the rich and the impoverished became more pronounced during this time, as wealthy people and big business received tax cuts and social benefits were stripped. Much of hip-hop music reflected the desperate conditions of the era. Public Enemy continued to document societal ills, while consciousness groups came of age, offering pro-Black messages and dis- patches of Afrocentrism. Meanwhile, the genre faced a backlash that permeated most mainstream media outlets, which often blamed hip-hop music for violent incidents at concerts.

Afrika Baby Bam (artist, producer, Jungle Brothers): There was the initial impact with the breakbeat days and the sound system up in the Bronx and the drum machines. Cats would be having ideas, getting together, freestyling, and using a bit of the records for the call-and-response action that you heard on the tapes, mixed in with your own story, and it was kind of like it was in your blood. ’Cause you connected with it and you could relate to it so strongly.

Even if you didn’t have a drum machine or access to a studio, you go through some joints and beats, records you would take off the radio, that you think would work, make a little pause tape. Or you pull out your notepad and you start writing some lyrics and you create that magic that you heard.

And that’s why groups like Run-DMC were the forerunners of taking it different places and through different mediums. It was like, “Yo, see look, they was just on MTV. Look, they was just on the radio over here. Look, now they at Madison Square Garden.” It’s not like they’re only in their neighborhood at a jam. “Oh, they’re in this magazine, now they’re in this newspaper.” That was the little telltales.

DMC (artist, Run-DMC): It wasn’t a thing of being accepted, trying to be famous. We became famous because of the brilliant things we were creating.

Afrika Baby Bam (artist, producer, Jungle Brothers): There’s so much more creativity to come that could get it to where it is today, or where it was in the ’90s when they had a full hip-hop radio format from Hot 97 to the Baka Boyz, to Sway & Tech. It was like, “Yeah, this genre can hold down a whole station twenty-four hours, because there’s so many variations and offshoots of the rudiments that still isn’t here yet, that could be.”

You saw that when the Fat Boys had a beatbox. Doug E. Fresh was beatboxing with Slick Rick’s storytelling. You had Biz Markie beatboxing, but doing comical stuff, then you had the female rapper. Then the drum machine with Davy D just making instrumentals. A lot of those rap records had one instrumental cut on the album for DJs. So, there was lots of different techniques that we knew right away, but again it was like all this ground is uncovered.

“Cats would be having ideas, getting together, freestyling, and using a bit of the records for the call-and-response action that you heard on the tapes, mixed in with your own story.”

Rakim Allah, born William Griffin, grew up in Long Island’s Wyandanch, surrounded by music. His aunt was the R&B great Ruth Brown. In 1985, another rapper had stood up Eric B., a DJ who had established a relationship with Marley Marl. Eric B. was now on the hunt for an artist to align himself with. A promoter recommended Rakim, and eventually the new DJ/MC pair headed over to Marley Marl’s place to cut their demo.

For many, there is Rakim followed by every other artist who has ever touched a microphone.

Marley Marl (producer, Juice Crew): When I first heard Rakim, I knew there was something special. He wanted to rhyme off of slower beats, so we did the slow “My Melody” first, and then we picked the tempo up on the second song, which was, “Eric B. Is President.”

MC Shan (Juice Crew, Queensbridge): I recorded the vocals. Rakim had a funny style. His style was laid-back—and I can’t say nothing, I’m like the main creator of laid-back styles—but his was laid, laid-back. So me and Marley laughed at him.

Marley would say, “Tell him to change the style.”

Ra say to me, he’d go: “Yo, Shan, come on. Nobody don’t tell you how to rhyme. How you going to tell me how to rhyme?”

And I just had to look at the nigga and say, “You know what? He’s right like a motherfucker. Do your thing.”

Marley Marl (producer, Juice Crew): I figured that we was just making a demo that I didn’t know if it would have even seen the light of day. I didn’t know what Eric was going to do with the tapes from the studio.

The pair dropped “Eric B. Is President” and “My Melody” in 1986. Their debut album, the following year’s Paid in Full, from 4th & B’way Records, served as a challenge to all other artists and producers: The craft had advanced, and it was time to modernize.

Rakim’s complex flow harmonized with the soundscapes Eric B. provided using sampling. Nowhere was the sync more complete than in “I Know You Got Soul,” which helped to popularize the use of James Brown samples in hip-hop.

Dante Ross (A&R, producer): We watched the change right in front of us. When we first heard that shit, no one heard nothing like that. And then when he followed up with “I Ain’t No Joke,” “I Know You Got Soul,” and other big records, it was like forget it. We knew it wasn’t a one-time-only thing.

You got to remember, too, “My Melody” and “Eric B. Is President” are both hit songs, not just one. That record was like the longest-living hip-hop 12-inch of all time, probably. He reinvented the wheel right in front of us. But he’s not the only one reinventing the wheel. At that time period, rap music grows in leaps and bounds.

Rakim is revered for his imprint upon legions of lyricists who followed him. Before Rakim, most artists followed rhyming schemes popularized by the likes of Run-DMC and LL Cool J. Rakim’s flow was built on more intricate rhyme patterns; he challenged other artists to up their skills, and provided a figure for a younger generation— including Nas and Jay-Z—to study and emulate.

Dante Ross (A&R, producer): Rakim is very interesting, because he’s from Brooklyn but grew up in the suburbs. I always feel like there’s this wave of guys who were suburban rappers, De La Soul included. They had the ability to hone their craft in their basement with two turntables and a microphone—even Run-DMC were suburban kids, kind of. It no longer was the Bronx and Harlem. It’s this wave of guys from around the way, out in Queens and Long Island and other places, who were allowed to hone their craft within the house.

Skillz (artist, Virginia): Rakim was super cool; he always just seemed calm.

DJ Clark Kent (producer): It’s almost like you never, ever saw him sweat. I don’t think I ever saw him in any mood but “I’m a god of rap.” I will say this, he is the god. He’s got one of the best sense of humors. He’s funnier than hell. He’s just a regular dude. He just can out-rap everybody.

“He reinvented the wheel right in front of us. But he’s not the only one reinventing the wheel. At that time period, rap music grows in leaps and bounds.“

Deadly Threat (artist, Los Angeles): We were used to a certain style, a certain type of finesse, and he was just a breath of fresh air.

DJ Clark Kent (producer): I always say Grandmaster Caz is the first best MC. The next best MC was Rakim. But Rakim was the most important MC ever. And I say that because everybody was rapping before Rakim. Then Rakim comes and everybody starts rhyming.

It was about “I take seven MCs, put ’em in a line. / And add seven more brothers who think they can rhyme. / Well, it’ll take seven more before I go for mine / Now that’s twenty-one MCs ate up at the same time.”

It was about saying dope rhymes and saying them well. Not singy-songy rapping shit. We’re not at a party no more. We’re in a booth and we’re going to show you that you have to be fuckin’ amazing. Rakim changed the way MCs rapped. Dude jacked them right out the gate.

Skillz (artist, Virginia): Rakim was probably the first rapper where what he was saying was good enough. He captivated you enough with his voice and what he was saying. And that super-cool demeanor just struck me as something special. He could say one thing, and let’s say we got three people listening. We all could interpret that one thing different ways. And I never knew whether or not it was voluntary or involuntary. That just made him genius to me.

Deadly Threat (artist, Los Angeles): He really turned it on, to where it was not just rhyme-like but a totally different style of music. And that was refreshing to not just a lot of the MCs, but as well as to society.

Bun B (artist, UGK): The way that people were able to express themselves, the way people were able to present themselves [in hip-hop at the time], it was a new way of looking at young Black men. The confidence, the swagger, the jewelry. Particularly, for me, Rakim.

Rakim’s prose and Rakim’s discipline to his craft, his level of confidence was really unmatched, and I think it all came together for me with “Microphone Fiend.” Just the way the video was shot, the way they moved. I want to walk in a world like that. I want to be the man like that. And that’s when I went from probably just looking at hip-hop and embracing the culture, to actually wanting to be an active part of it.

Capital D (artist, Chicago): Rakim is the difference between, say, military music and jazz. When you listen to Run-DMC it was, “dat, dat, dat” with the patterns. And then Rakim, everything is: “Follow me into a flow.” Everything is just a lot more rhythmic.

It’s a before-and-after. He basically kind of broke everybody’s mind. Rakim had enough of a message, but he wouldn’t beat it over the head. Every MC after him had some remnant, and owed something to him for breaking that mold.

Deadly Threat (artist, Los Angeles): I think everybody at the time could agree, he really, really brought us into a new era and style of rap. If it wasn’t for him, a lot of people wouldn’t have even attempted to go in different other directions.

Styles P (artist, the Lox): It shifted the culture. He sped it up. It’s kind of like he was the computer of rap. It’s like the introduction of something more advanced.

______________________________

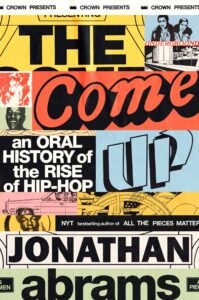

From the book The Come Up: An Oral History of the Rise of Hip Hop by Jonathan Abrams. Copyright © 2022 by Jonathan Abrams. Published by Crown, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Jonathan Abrams

Jonathan Abrams is an award-winning staff reporter for The New York Times. He is the bestselling author of two previous books, Boys Among Men and All the Pieces Matter. A graduate of the University of Southern California, Abrams was formerly a staff writer at Bleacher Report, Grantland, and the Los Angeles Times.