A Brief History of New York’s First Great Architectural Firm

Henry Wiencek on the Eccentric, Creative Minds Behind McKim, Meade and White

“He can draw like a house afire,” Charles McKim told his business partner, William Rutherford Mead, as he urged Mead to make Stanford White a partner in their tiny architectural firm. Stan had returned to New York from Paris in September 1879 and had left his old firm. In the company’s office at 57 Broadway, Mead pulled out a yellow scratch pad and jotted a profit-sharing proposal: McKim—42 percent; Mead—33 percent; White—25 percent. White accepted, and the firm of McKim, Mead & White was launched. Stan wrote to “Beloved Snooks” in Paris that his share was not high, but “if I can get a little decorative work outside of the office, I shall manage all right.”

McKim, Mead & White occupied the fifth, top floor of 57 Broadway in a now-vanished building on the north side of Exchange Alley in lower Manhattan. From the windows, a daydreamer could look down on Broadway’s rumbling traffic or gaze farther out at a calming panorama of New York Harbor with its expanse of islands, scudding clouds, and swooping gulls.

The name McKim, Mead & White evokes the image of three portly, middle-aged men, because the most frequently reproduced photograph of the trio was taken around 1905, when all three partners were in their fifties. In the early 1880s, however, youth and energy characterized the men who occupied the top floor of 57 Broadway. (There were no women in the firm.) In an era when the architecture business was new, McKim, Mead & White was its own school, an incubator of talent, the place where young Stanford White patrolled the drafting room pounding on tables, snatching up drawings, and yelling “This looks like Hell!” or “Swell, isn’t it?”

Stan arrived as a partisan of Richardson Romanesque. He and Louis Comfort Tiffany collaborated on a massive house for Tiffany and his extended family at the northwest corner of Madison Avenue and 72nd Street, with fifty-seven rooms and a three-story studio for Tiffany. It was a fantasy castle both on the outside and the inside, “the realization of an architect’s dream,” wrote one critic. White’s taste for Richardsonian sturdiness was evident in the roughhewn blocks of bluestone forming the ground floor and the twenty-five-foot-wide iron portcullis guarding the arched entrance. But above, the building was a festive amalgam of turrets, balconies, gables, and colored bricks. While scouting for bricks at New Jersey’s Perth Amboy Terracotta Company, Stan passed a stable constructed from oddly hued discards, failed experiments in mixing colors.

When a beige brick caught his eye, he told company officials this is what I want. Immediately dubbed the “Tiffany brick,” it was adopted by other architects and designers and led to the new, splendid, sunny look of 1880s and ’90s New York. Not only did White enhance the color palette of brick and terracotta, he made the colors dance before the eye with glazing that was speckled or mottled. His instinctive, painterly love for the picturesque clashed with a rising taste for the austere symmetries of the Renaissance, doggedly advanced by McKim and a widely admired assistant, Joseph Wells.

In an era when the architecture business was new, McKim, Mead & White was its own school, an incubator of talent.

Poor, sickly, self-taught, reclusive, nasty in stating his opinions, and iron-willed, Joseph Wells possessed an artistic soul that was purer and more unforgiving even than White’s close collaborator, the sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s. A Bostonian, he became interested in architecture as a high school student but could not attend college because his family exhausted its funds sending his older brother to MIT. He found work at the Boston firm of Peabody & Stearns, rising to chief designer at the age of twenty-one. A friend from those days, the architect Charles Howard “Howdie” Walker, described him as intensely private and serious, with no interest in sports and parties. He connected with people who shared his passions for music and architecture. In a journal entry, Wells defined his cultural ideals:

The classic ideal suggests clearness. Simplicity, grandeur, order, and philosophical calm—consequently it delights my soul.

The medieval ideal suggests superstition, ignorance, vulgarity, restlessness, cruelty and religion—all of which fill my soul with horror and loathing.

The Renaissance ideal suggests a fine and cultured society, with its crowds of gay ladies and gentlemen devoted to the pleasures and elegances of life—which excites my admiration, but not my sympathies.

It is inconceivable to me how any civilized architect can design in the Romanesque or Gothic styles.

Howdie Walker recalled the night Wells appeared in his apartment with large scrolls. He unfurled them and tacked them onto the wall: two exquisitely detailed drawings of Italian Renaissance palaces, unlike any drawings done before by an American architect.

Wells’s devotion to architectural purity cost him his job in Boston. Told by one of the firm’s senior partners to add ornamentation to the design for a pyramid atop an office building, Wells flatly refused. Nothing could induce him to put decorative crust over a pure geometric form. The partner overruled him; Wells thereupon quit and went to New York. McKim and Mead hired him several weeks before they hired Stan.

Wells was as quiet as White was loud, as eccentric as White was flamboyant, as ascetic as White was sensual. Both born in 1853, White and Wells formed an immediate friendship based on a shared love of music and architectural beauty. Not long after being hired, Wells somehow got the funds to undertake an architectural tour of England, France, and Italy. It would stretch from July 1880 into the winter of 1881. As he toured, he strongly missed White, sending him detailed letters about what he was doing and seeing.

The charming scenery of the French countryside that had so enchanted White and Saint-Gaudens tested Wells’s purism. He would not allow himself to savor sensual visual experiences lest he fall into the snare of sentiment and “a morbid love of the picturesque.” Instead, he went into raptures over Italy’s “great and grand and dignified” relics of the Renaissance.

At the end of his tour, having seen the landmarks of Europe for himself, he felt independent and unafraid of deflating Stan’s boastfulness. One day when he was back in New York, White rushed into Wells’s office, tossed a drawing onto his desk, and declared, “There, that is as good in its way as the Parthenon!” Wells responded, “And so fried eggs in their way are just as good as the Parthenon.”

Wells’s great mind inhabited a small set of rooms in the six-story Tuckerman Building on Washington Square. His apartment became a gathering place for White, Saint-Gaudens, and a few others of their circle who passed long evenings discussing art, architecture, and literature.

Wells’s revolt against White led to the making of one of New York’s greatest houses. In 1882 the railroad magnate Henry Villard commissioned a mansion (it still stands, now converted to a luxurious hotel) at Madison Avenue between 50th and 51st. White made preliminary drawings for the facade in the Romanesque style, then departed on a long trip. With construction deadlines looming, Mead turned the assignment over to Wells, who threw out White’s concept and substituted a stately Italian Renaissance design.The five-story edifice would rank among the largest residential buildings in the city. Officially named the Villard Houses, the mansion appeared to be one residence but actually contained six separate homes under one roof, with more than thirty bedrooms and ten bathrooms.

If White complained when he returned to find Wells’s insubordinate design, there is no account of it. Rather, inside Wells’s sober facade, White created a resplendent interior with relief figures by Louis and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, stained glass by John La Farge and Maitland Armstrong, and paintings by Frank Bacon. White deployed surfaces of gold, leather with intricate patterns of nailheads, rich tones of marble, mosaics. The barrel-vaulted ceiling of the music room soars about thirty feet high, with a balcony for musicians reached by a hidden stairway. The mansion’s marble stair hall focuses on a magnificent clock, designed by White and Saint-Gaudens, built into a wall and surrounded by the figures of the zodiac. For the hands, Saint-Gaudens and White designed golden sunrays tipped with silver. One critic sensed “the radiance” of White’s interior and called Wells’s facade “delicate and self-repressive,” accurately reading the conflicting psyches of the two architects.

Perhaps from a perfectionism that could never be satisfied, perhaps from clinical depression, Wells turned triumph into torment. Though critics hailed the Villard mansion, Wells despaired because “it can never be popular.” He thought only a handful of connoisseurs could grasp the nuances of what he had wrought. Despite his disappointment, Wells praised Stan’s work, singling out the staircase with the zodiac clock and the dining room with a massive marble fireplace by Saint-Gaudens: “decidedly the most beautiful interior work in the country.”

The success of the Villard mansion decisively shifted McKim, Mead & White to the Renaissance style. White apparently put aside his passion for the Romanesque as quickly as he had relinquished painting for architecture. At any rate, Richardson Romanesque slid from its height of popularity and became, remarkably, “the object of scorn,” as Richard Guy Wilson observed. At the time, the critic Montgomery Schuyler wrote that Richardson and his followers “produced monstrosities throughout the country.” The stateliness of the Renaissance style—so evocative of nobility, inherited wealth, and inherited power—was especially apt for an elite trying to seek legitimacy. In purely architectural terms, the Renaissance mode suited the urban streetscape better than the Romanesque.

In letters to Cass Gilbert, Wells chronicled his increasing disappointment in Stan, both as an architect and as a friend. White cared more “to make a social figure” and less about his art: “I almost regard him as a brilliant decorator not an architect. He is not equal to the mental strain necessary to gradually form a good style.” He confessed, with deep hurt, that Stan seemed to have lost interest in him: “A man who treats his old friends coldly I can hardly forgive.”

As the firm grew and the drafting room got more crowded, Wells found a trick that calmed him. One day he came to the office carrying a novelty toy, a stuffed chenille monkey on an elastic band. With glee, he showed it to all the draftsmen as if he were introducing a new friend. He would retreat into his little office and lean out the window overlooking Broadway, bouncing the monkey on its elastic band and staring below at the passing scene for hours on end, apparently doing nothing. Suddenly he would leap to his table and make detailed drawings at an astonishing rate. The noise and tumult of Broadway inspired him, but in his notebook he declared: “New York is a carnival of vulgarity. Nothing short of a great man can successfully resist its disintegrating influences.” He inveighed against the firm’s Gilded Age patrons with their “vain and senseless trappings of vanity and folly—balls, parties, late suppers, dress coats, painted shoes, aesthetic cravats.” This was the world White reveled in.

Cass Gilbert considered Wells a complicated, one-of-a-kind artist: “Of all the miserable, bilious, unhappy, pessimistic, misanthropic geniuses, he is at once the worst and the best. No kinder man lives that I know of, no more gentle sensitive nature, in man, has come before my observation, unselfish, not egotistical, caustic yet humorous, timid and retiring—never fully understood except by his intimates, he is unique.”

Arguments over design could grow quite theatrical. One afternoon a group of top talents assembled at 57 Broadway to judge a competition. Three walls of a conference room were covered with drawings for courthouses, libraries, and other public buildings, submitted by outside architects. A jury consisting of White, Saint-Gaudens, McKim, Thomas Hastings, and John Carrère circled around the small room. The careers of the architects, who were not present for the judging, hung in the balance, so a group of young McKim, Mead & White draftsmen gathered to watch.

According to a draftsman’s account of the meeting, Hastings argued passionately for a drawing that conveyed a strong sense of direction, a sense of actual movement: “It would crawl straight at you,” he said, “and nothing could deflect it from its path.” Perhaps with a subtle raising of an eyebrow, McKim murmured his vote for a design that “would not crawl in any direction.” Saint-Gaudens addressed the placement of statuary; White washed his hands of the whole business. The judgment came down to a contest between Hastings, “who hopped about twittering like an excited sparrow,” and McKim, who quietly insisted that a building should not move. The draftsman wrote: “If Hastings were right, this building must have the latent qualities of a tortoise, which seemed to be absurd. I agreed with McKim that any building must be as static as a milepost.” The jury couldn’t decide.

Stan often sought advice from George Fletcher Babb, an experienced architect who was seventeen years older. Disheveled and sometimes quite noticeably unbathed, Babb spoke in mumbles and half sentences that Stan struggled to decipher. During the fraught creation of the Farragut, Babb had thrown Stan into a panic with a remark that the pedestal’s curved lines were all wrong. After uttering this vague but devastating critique, Babb “shut up like a clam,” offering no solution. Babb’s praise could be equally Delphic. When he liked something, his response was “Hmmm,” which, Stan said, “is a lot for him.”

The firm grew explosively. McKim, Mead & White opened in 1879 with four drafters; by 1886, the firm had seventy. Just three years later its 120 architects, draftsmen, and other staff members moved to larger quarters in the Mohawk Building at 160 Fifth Avenue. But in the early days, the top floor of 57 Broadway housed a small creative fraternity. One assistant later wrote: “Those were exciting days. Architecture was the only art on earth and its sanctuary was at 57 Broadway.”

Just twenty-nine feet wide but very deep, the office at 57 Broadway had a small reception room for meeting clients. The three partners had to make do with offices about six feet square, barely large enough for their cheap rolltop desks. The tight space enforced collaboration. The partners spent much of their time in the communal drafting room, where the draftsmen labored at a dozen long tables. At one end stood a swinging door that everyone approached with caution because, as one employee remembered, “Stanford White was likely to plunge through it at an incredible rate of speed.” Stan wore see-through silk shirts of pale blue and green, some with bold mauve and white stripes, all slightly oversize so they would billow as he dashed through the office as if propelled by the wind.

McKim, Mead & White quickly became the place for aspiring young architects, who avidly sought jobs there despite miserly salaries. One draftsman worked for months at six dollars a week before he dared ask for a raise, pleading that he needed new shoes. Several apprentices went on to spectacular careers on their own. Cass Gilbert, after a two-year stint at the firm, departed for his hometown of St. Paul, Minnesota, won distinction as the architect of state capitols and major public buildings, then returned to New York and designed the Woolworth Building, the world’s tallest skyscraper when it was completed in 1913. Thomas Hastings and John Carrère built the New York Public Library in 1911. Henry Bacon designed the Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, completed in 1922.

McKim, Mead & White quickly became the place for aspiring young architects, who avidly sought jobs there despite miserly salaries.

William Rutherford Mead, born in 1846, was a year older than McKim and seven years older than White. He was extremely handsome, with twinkling dark blue eyes, a radiant smile, and, when the mood was on him, a joking manner. Because he had spent a year working for an engineer after graduating from Amherst in 1867, he dealt with nuts-and-bolts issues of heating and plumbing. He also kept the office running, very calmly, wreathed in thick smoke from the cigars he smoked all day, roaming the office in a slow, lumbering, bearlike gait. Stan and McKim called him “Dummy” from his habit of saying as little as possible and because he appeared to be much less shrewd and tough than he actually was. Averse to conflict, he would silently back out of the drafting room when confronted with a bothersome question. Though he enjoyed telling jokes, if the young men tried to banter with him, he turned away, keeping his emotional distance. It was his job to lay people off, which he hated to do. He would come into the office early to slide pink slips into the mailboxes of the unfortunate ones so that he would not have to face them.

Mead exerted a quiet control over his two partners, nudging McKim forward and trying to restrain White from spinning out of control. Saint-Gaudens captured the tripartite relationship in a cartoon showing Mead on the ground struggling to control two airborne kites labeled McKim and White flying off in opposite directions.

In appearance and temperament, McKim and White could not have been more different. As White surged through the office bellowing orders and pounding tables, his six-foot-tall figure seemed even more commanding with his flamboyant, spiky red hair. By contrast, McKim—bald, with a sandy fringe of hair and a drooping mustache—stood about five foot seven and spoke in a low, mannered tone. He suffered from depression that sometimes disabled him. He pored over illustrated architectural tomes in pursuit of classical precedents and precision. He sweated over composing a telegram. An assistant once sat with him while he stewed over a text of about ten words. For an hour, McKim mulled synonyms and alternate phrases.

Once while designing a cornice, he settled next to a draftsman with a sharpened pencil and indicated exactly where he wanted certain horizontal lines to fall. In silence, McKim contemplated the paper for a good long time, then said “just take out that middle line and move it up a little.” The assistant moved the line. McKim once again fell into a long, silent study. Then: “No, put it back where it was—perhaps a little lower.” Writing in the 1930s, White’s first biographer, Charles Baldwin, noted that McKim’s quiet demeanor masked a strong will, which Baldwin affectionately characterized as “rodent-like determination.” Fighting through depression and doubt (like Saint-Gaudens), McKim produced masterworks that drew on his absorption in historical precedents, which he deftly adapted for modern needs: Pennsylvania Station, the central campus of Columbia University, the University Club, the Morgan Library, and the Boston Public Library, to name but a few.

Though he had read Ruskin, Stanford White boasted that he never relied on books about architecture and never would: “Hadn’t time!” When a draftsman, in despair, showed him a plan with an axis—the sacrosanct straight line, the pillar that holds a visual concept together—that couldn’t be maintained, Stan told him, “Bend the axis!” Along with his creative genius, he brought his network of social connections to the firm—which led to a torrent of commissions. He came down hard on his cohort of eager if inexperienced young draftsmen to get each and every job done. The smart ones endured his explosions and bullying because they sensed he was trying to turn them into working architects, making “silk purses out of very unpromising material,” as one of them said. He would suddenly appear at a draftsman’s table and “in five minutes make a dozen sketches…slam his hand down on one of them—or perhaps two or three of them if they were close together—say ‘Do that!’ and tear off again. You had to guess what and which he meant.” He almost never explained, because he expected his apprentices to look, learn, and make decisions.

Harold Magonigle, the fledging architect who had suffered through McKim’s deskbound process of repeatedly drawing and erasing lines, took on a project for White and discovered an entirely different style of creativity—and energy. White put Magonigle in charge of designing and supervising the construction of the interiors for a mansion in Westchester County. Magonigle designed an elaborate coffered ceiling, profuse with plaster rosettes. When the mansion was finished, White took one look at the ceiling and blurted, “Well if that isn’t the goddamdest lookin’ ceiling I ever saw—gimme a hammer! gimme a ladder!” He proceeded to knock down rosettes, not all of them but an instantly, instinctively chosen group of offenders, whooping with delight as each plaster flower fell with a satisfactory crash. Magonigle was awed by White’s grasp of space and decoration, and he had to admit that the ceiling looked much better after his boss’s deletions. The workmen, however, gaped in dismay at the mess and, after White left, declared that the architect was “looney.”

One assistant, Egerton Swartwout, remembered White “towering over some poor wretch who thought he’d really done a good job,” bellowing, “My dear sir will you kindly tell me what in God’s name that is!” Then, tugging fiercely at his mustache, he reconsidered. “Well all right,” he said, as he snatched the sketch and ran off. Another favorite comment was “This looks like Hell!” Either bellowed in person or scribbled on a drawing late at night when, alone in the empty office, White went from table to table examining the previous day’s work. But he was equally generous with praise, offered loudly and publicly. Waving a drawing, he’d call out to Mead, “Look at this, Dummy! Swell, isn’t it?”—making sure the draftsman was within earshot of the accolade. When deadlines loomed, he couldn’t bear to watch a draftsman labor over a drawing with a T-square and compass. With one brusque sweep of his arm, he would knock the instruments aside and in minutes make a detailed drawing freehand.

White came into the office at eight or nine in the morning, left at seven, and often returned late in the evening after the opera or the theater. He worked on Sundays and holidays. As one assistant recalled, “You could never tell when he’d show up.” One night he worked side by side with a draftsman on a drawing until two a.m. and then had the assistant meet him at six-thirty a.m. to search the city’s shops for stained glass, wood carvings, and fabrics.

__________________________________

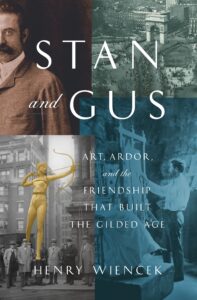

Excerpted from Stan and Gus: Art, Ardor, and the Friendship That Built the Gilded Age by Henry Wiencek. Copyright © 2025 by Henry Wiencek. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, an imprint of Macmillan, July 2025. All rights reserved.

Henry Wiencek

Henry Wiencek is a prizewinning historian and writer and the author of several books, including The Hairstons: An American Family in Black and White, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award, and, most recently, Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves. He lives in Charlottesville, Virginia.