A Brief Guide to Tintinology

Essential Reading for Armchair Tintin Scholars

Tintin, everyone’s favorite intrepid Belgian boy reporter, made his first-ever appearance 88 years ago today, in a 1929 issue of Le Petit Vingtième. His creator, the Belgian illustrator Hergé (Georges Remi) was only 23 years old at the time, but Tintin would be the work of a lifetime, growing into one of the most popular and beloved comics characters in the world. But Tintin isn’t just an adored childhood figure who was once honored by the Dalai Lama—in fact, a whole field of scholarship now known as “Tintinology” has grown around Hergé’s deceptively simple Adventures of Tintin. There are now scores of texts on both Tintin and Hergé—here’s a brief guide to some of the most interesting ones.

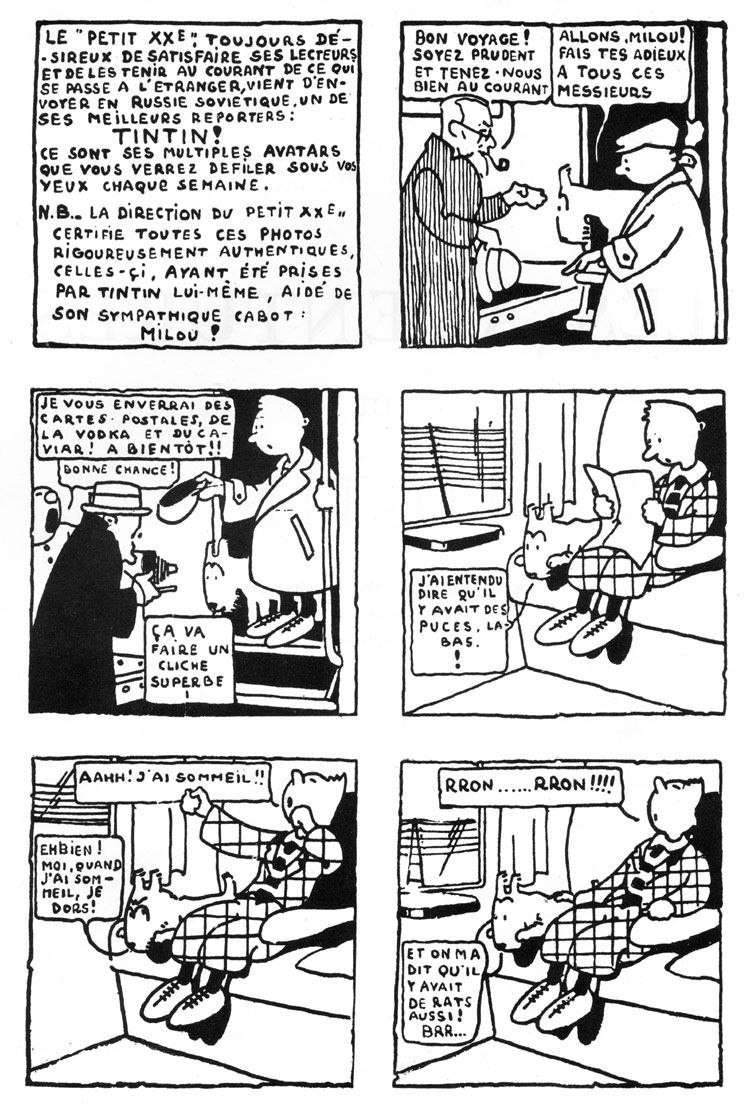

But first, to begin at the beginning, Tintin was introduced with the following missive from the paper, before the very first panels that would begin the story soon to be known as Tintin in the Land of the Soviets:

Is that in French? An (amateur) translation:

Le Petit Vingtième, always eager to satisfy its readers and keep them informed of what is happening abroad, just sent to Soviet Russia one of its top reporters: Tintin! These are his many incarnations that you will see scrolling past your eyes each week.

NB: The Management of Le Petit Vingtième rigorously certifies all of these photos to be authentic, these have been taken by Tintin himself, helped by his friendly mutt: Snowy!

Tom McCarthy, Tintin and the Secret of Literature

If you can believe it, the first work of Tintin criticism to be originally written in English was 2006’s Tintin and the Secret of Literature by English novelist and General Secretary of the International Necronautical Society Tom McCarthy—his recent Satin Island is brilliant, by the way, not to mention Remainder and C. Among other things, the book will convince you without a doubt of Tintin’s worth as literature, and the importance of studies around it (this is why it goes first). In the book’s introduction, McCarthy writes,

“Like many of the very best writers (Shakespeare and Chaucer spring to mind in this respect), Hergé has bequeathed a bestiary of human types. Taken together, they form a huge social tableau—what Balzac, describing the network of characters spread across his books, calls a comédie humaine, a “human comedy”—made of emirs, barons, butchers whose telephone numbers keep getting confused with one’s own and ghastly petit-bourgeois louches who are too socially insensitive to realise when neither they nor the insurance they peddle are wanted. You know the type: you might even, in your more honest moment, detect a strain of it in yourself. When these figures are thrown together in the Tintin books the tense, loaded situations that arise are managed with all the subtlety normally attributed to Jane Austen or Henry James. … A huge symbolic register runs through the books, turning (as we will see) around signs such as the sun, water, the house, even tobacco—a register that, consistent and expanding at the same time, is worthy of a Faulkner or a Brontë. Played out against a backdrop of wars, revolutions and recessions, of technological progress imbued with an almost sacred aspect, not to mention old gods who steadfastly refuse to die, all of this amasses to an oeuvre that, again like that of many of the best writers—Stendahl, George Eliot or Pynchon, for example—forms a lens, or prism, through which a whole era lurches into focus.”

But Tintin has something more than just the markers of literature, McCarthy asserts.

“If you want to be a writer, study The Castafiore Emerald, and study it carefully. It holds all literature’s formal keys, its trade secrets—and holds them at the vanishing point of plot, where nothing whatsoever happens. … [Yet the comic medium] still occupies a space below the radar of literature proper. Which leads us to the second paradox: this below-radar altitude, this blind spot, this mute pocket is, as we already know, the zone where real action takes place. Let’s call it a degree-zero zone, a kind of loaded anti-space held in reserve. If literature itself has an ultimate truth, a deeper-than-trade secret either unexpressed or inexpressible, it is in precisely this kind of space that we should look for it.”

Michael Farr, Tintin: The Complete Companion

This one’s a classic—an illustrated history by Michael Farr, often cited as the world’s top Tintinologist and the author of more than a dozen books on Hergé—any serious reader of Hergé’s work probably already has it on their shelves. This is valuable book for contextualizing Tintin, filled with sketches, photographs of locations that Hergé drew inspiration from, scraps of artifacts and other details that deepen the stories and shed light on Hergé’s careful process.

Jean-Marie Apostolidès, The Metamorphoses of Tintin, or Tintin for Adults

First published in French in 1984 and only translated into English in 2010, this is one of the essential critical studies of Tintin, examining both the comic and Hergé himself—tracking the apparent changes in each over the years—and arguing for the oeuvre as a work of legitimate literature. Important reading to contextualize the racist overtures of some of the early work in particular.

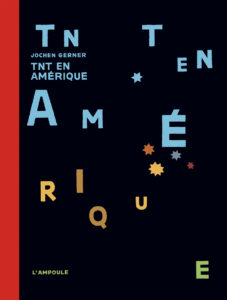

Jochen Gerner, TNT En Amerique

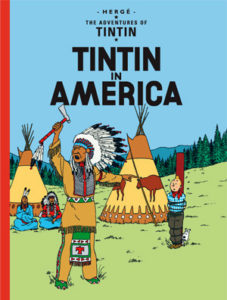

I’m a fan of art about art, so I find this particular book fascinating. You’ve heard of blackout poetry—well, this is a blackout comic, taking Tintin in America as its source material, and coming out with something wildly different, almost impressionistic (you’ll notice the similarities between this book and McCarthy’s, in which it is excerpted). I’d say it brings the text closer to poetry—or maybe a video game. Either way, it’s a new way to look at an old classic. You can see sample pages on the publisher’s website.

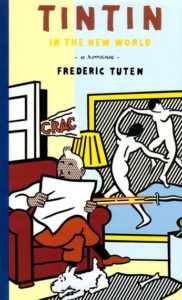

Frederic Tuten, Tintin in the New World: A Romance

Here’s another artistic take on the original books—this one a novel, that—gulp—imagines our well-known one-dimensional virgin falling in love. But it’s actually not all about sex—although the sex is quite funny (“‘Tintin,’ Clavdia whispers, kneeling beside the bed, ‘you are so strange, so hairless.’…”). It’s all a sort of fever dream pastiche of Tintin mixed with The Magic Mountain, and it has polarized both readers and reviewers. In the New York Times, Edmund White called it “queerly beautiful” and wrote, “Who can resist a text that interpolates Snowy’s thoughts and canine romances into the running narrative, that drops certain corny paragraphs into quotation marks in order to suggest their bogus novelistic tone, but that somehow remains—dare I say it?—sincere?” Publisher’s Weekly on the other hand, sniffed that “everything about this painstakingly crafted but hollow novel smacks of the academy, from the slightly passé mix of popular and literary genres to the appropriation of easily recognized texts.” I suppose any true Tintin scholar should read and decide for themselves.

Tintinologist.org

This is a bare-bones fan website, the largest in English, which brings such delights as this analysis of Tintin’s meals and this full list of all of Tintin’s disguises. A healthy afternoon’s browse.

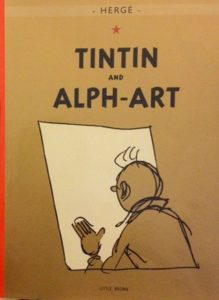

Hergé, Tintin and Alph-Art

Hergé’s unfinished final installment in the Tintin adventures, which was to be a murder mystery set in the modern art scene of Brussels. When Hergé died, he left behind some 150 pages of notes and sketches, a selection of which are published in this volume. Essential reading for those interested in Hergé’s process, as well as any dying for a final sip of the famous boy reporter.

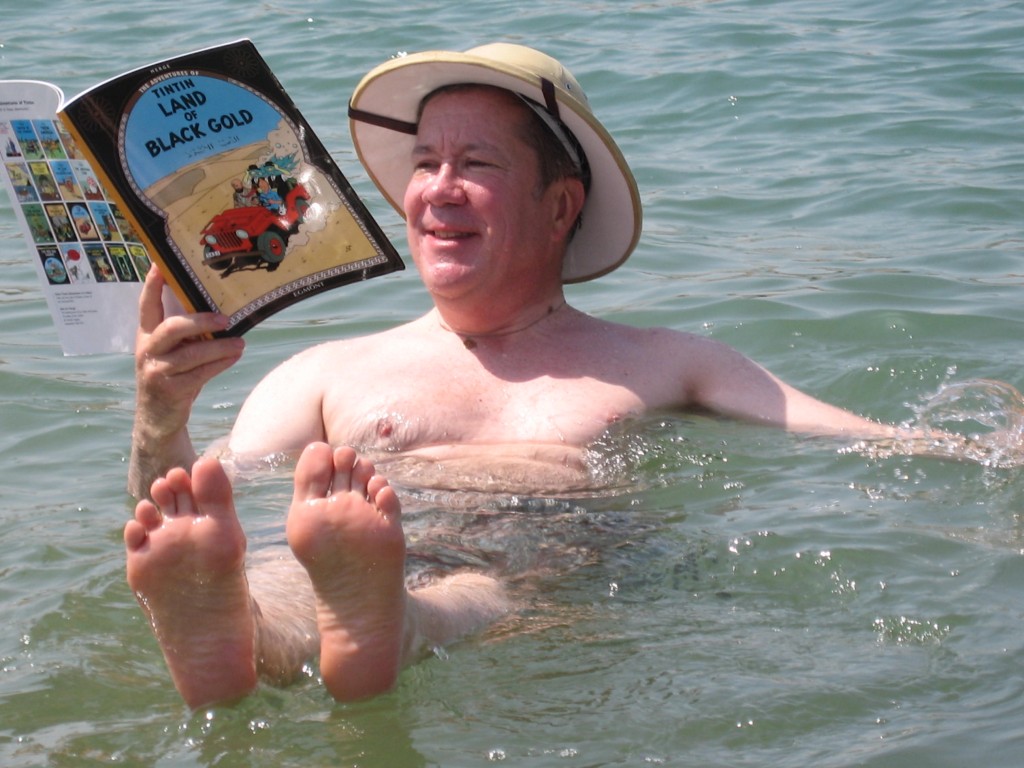

Hergé, The Adventures of Tintin

If you’ve gotten here, you’ve probably already read these, but just in case: always go to the source. I particularly recommend reading the early books, the ones not commonly included in the paperback series—yes, they’re racist (what else do you expect from the 1930s), but they give lots of insight into the core of this character, and the difference between Tintin and the Soviets and Tintin and the Picaros is truly astounding.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.