A Black Avant-Garde: How Lorraine O’Grady’s Literary Artwork Fused Poetry and Politics

Peter Trachtenberg Holds up the Frame to an Iconic Artist Who Redefined Being an Icon

Lorraine O’Grady didn’t become an artist until she was in her mid-forties. She was fifty-five when she had her first show. Still, at the time of her death at the age of ninety last December she had achieved iconic status in the art world, though “iconic” is probably the wrong word.

An icon is a single image that’s instantly recognizable. It’s Frida Kahlo with her unibrow and her wounds or Marina Abramovic undoing strangers with the vacuous neutrality of her gaze.

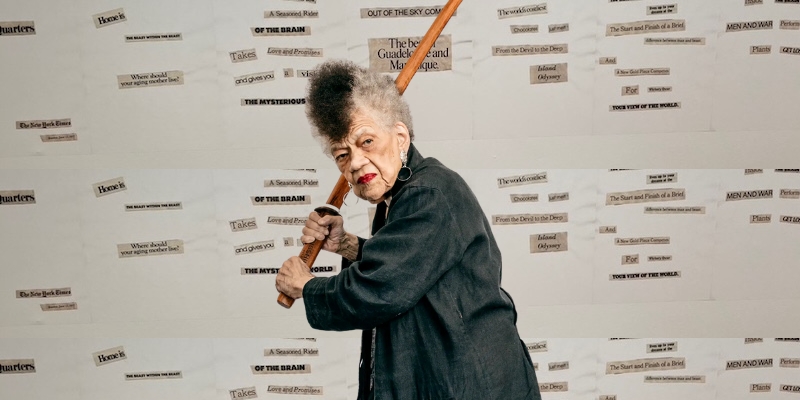

O’Grady was an icon that kept changing: the rogue debutante crashing art openings in a gown sewn from 180 pairs of white gloves; the creator of photo collages that placed her family members in conversation with Baudelaire and Baudelaire in conversation with Michael Jackson; the black-clad elder with a two-tone Mohawk that made her as spikily elegant as a wasp lip-synching to Anohni.

In all these incarnations and through multiple modes of expression, the concept-based artist turned received ideas of race, class and gender inside out and took a close look at their seams.

Something that may get lost in that outpouring of projects and personae is that O’Grady was a writer. She always saw herself as one. As a young woman she studied in the Iowa Writers Workshop, where she undertook a novel and translated another—Este Domingo, “This Sunday”—by the Chilean writer Jose Donoso, who was one of her instructors.

In all these incarnations and through multiple modes of expression, the concept-based artist turned received ideas of race, class and gender inside out and took a close look at their seams.

In 1992 she published the groundbreaking “Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity,” arguably the first work to call critical attention to representations of the Black female body and the truth those representations leave out. Even thirty-some years later, its aphoristic directness registers like a slap in the face, the kind that’s not meant to hurt you but to snap you out of hysteria:

The female body in the West is not a unitary sign. Rather, like a coin, it has an obverse and a reverse: on the one side, it is white; on the other, non-white or, prototypically, black. The two bodies cannot be separated, nor can one body be understood in isolation from the other in the West’s metaphoric construction of “woman.” White is what woman is; not-white (and the stereotypes not-white gathers in) is what she had better not be.

O’Grady’s writing wasn’t strictly textual; it included performances and photomontages. She often spoke of her practice as “writing in space,” a way of articulating ideas that couldn’t be expressed in other media. “Performance’s advantage over fiction was its ability to combine linear storytelling with nonlinear visuals,” she said. “You could make narratives in space as well as in time, and that was a boon for the story I had to tell.”

That story was partly autobiographical, following O’Grady’s passage from a childhood in a genteel West Indian immigrant family in Boston into a New York art world that in the early 1980s admitted few Black creators and tacitly required the few it did admit to pretend to be something else: “You had this weird spectacle of middle-class adult artists trying to pass as street kids,” she recalled.

She herself refused to pass. She’d gone to Girls Latin and Wellesley and had worked as an analyst for the U. S. departments of Labor and State, where her brief included reading ten national and international newspapers a day and, during the leadup to the Cuban missile crisis, complete Spanish-language transcripts of three Cuban radio stations. After a while, she said, she could feel language “collapse” into a “gelatinous pool.”

(Later that experience would launch a profitable career as a translator, not just of Spanish, but French, Italian, and, in a pinch, Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian. Once, when charged with vetting the translation of the text on ATM screens into Japanese, a language she didn’t speak, she relied on her hyperacute visual discernment to identify the inconsistencies in the kanji characters.)

Still, in her work autobiography takes a back seat to ideas, or serves as a vehicle for them. Her career-long project was the interrogation of the either/or binaries of race, gender, sexuality, and class and her argument that categories like whiteness and Blackness weren’t separate but interrelated and interdependent.

Much of her art was an attempt to free language from the strait-jacket of those binaries; not for nothing was her triumphant 2021 retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum titled both/and. The value she prized above all others was hybridity, or as she sometimes called it, ‘miscegenation,’ an openness to—really, an embrace of –seemingly contradictory states of thinking, feeling, and being.

Cutting Out the New York Times (1977) began as a flirtatious thank-you note to the handsome doctor who’d treated her during a cancer scare. It was inspired by a phrase she came upon in the Sunday paper: The doctor is operating again. (The reference was to the basketball great Julius “Doc” Irving.)

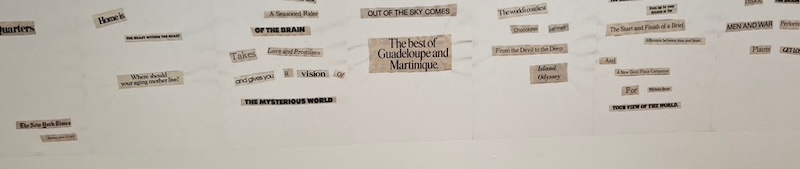

O’Grady cut it out and pasted it onto a sheet of blank paper; she found other words and phrases that seemed to follow from it and did the same, creating what she called “an imaginary love letter for an imaginary affair.” Over the six months from May 29, 1977 until November 30, she composed twenty-six visual poems with titles like “Conversations with Fata Morgana,” “The Right Face for the Right Job,” “The 99 Critical Shots in Pool.”

An example of O’Grady’s visual poetry

An example of O’Grady’s visual poetry

Like many poets, O’Grady adopted constraints. She made one poem a week, using only that Sunday’s paper, ads included, and making only one cutting per page. Each stanza was pasted on a separate sheet of paper. The varied fonts and gnomic wit suggested a mashup of Apollinaire and a kidnapper’s ransom note.

But the poems also did something to the language of the Sunday Times, which in the late 1970s was a secular Bible for millions of Americans well beyond New York City, defining for them what was worth thinking about, what one ought to be afraid of or look forward to or replay at the water cooler the next morning—”one” being, implicitly, white.

Under the cover of irony and whimsy, O’Grady wrenched the Times‘ language free of its familiar public associations; she made it both the signifier and the instrument of her own irreducible, Black, female interiority. When she sent her ex-husband a copy of the poems, he told her “it was like opening the Times and seeing the inside of your head.”

Much of O’Grady’s work involves similar reframings. In the most famous of her performances, the reframing is literal. In response to someone’s pronouncement that “avant-garde art doesn’t have anything to do with Black people,” O’Grady staged an intervention at the 1983 Afro-American Day Parade in Harlem during which she rode a float up Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Boulevard holding up an oversized gilt frame to the neighborhood’s streets and apartment buildings; outlined in this manner, the surroundings revealed a ghostly resemblance to the squares and palazzi of Canaletto’s Venice.

White-clad dancers circulated through the crowds holding up smaller frames and inviting anyone who wanted to pose as a living work of art. Lots of people wanted to: a beaming woman with an umbrella; a girl gleefully pointing through the frame at the photographer taking her picture; even a bashful cop.

“Frame me! Make me art!” they yelled to the dancers. “That’s right, that’s what art is! WE’re the art!”

By 1983 people who knew a little about performance art thought it traded in shock and provocation (some might have had in mind O’Grady’s earlier appearances as Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, a rogue debutante in a gown made of a hundred and eighty pairs of white gloves who crashed art openings and shouted poetry while lashing herself with a whip).

“Art Is…” traded in joy. Specifically, it traded in the joy of people who were commonly unseen in what was not yet called the mainstream media , or seen only in postures of menace or abjection.

In 1983 America had a president who’d proclaimed his faith in “states’ rights” not far from where three civil rights workers had been murdered by the Klan. So while the trope of the empty picture frame promoted enough general good feeling to be used in an ad for the 2020 Biden campaign, O’Grady was always clear that “Art Is…” wasn’t about how art is for everybody: it was, per curator Aruna D’Souza, “quite pointedly a work about Black people and their beauty, and their right to be at the center of the art world.”

In the 1990s O’Grady shifted into photomontage. The medium was well suited to the subject of hybridity since the photomontage is itself hybrid, bringing the documentary authenticity of the photograph into play with the flagrant artifice of the collage.

Sometimes she used found images, including her family photos. Sometimes she photographed each object separately and then meticulously intercut it with others. Typically, the photos were arranged as diptychs, a form that mirrors that of an open book and invites the eye to travel the way it does in the act of reading.

In the left panel of The Clearing, naked lovers—a white man and a Black woman—cling to each other as they float above an idyllic landscape where two children play on the grass. In the facing panel, the woman lies on the ground, arms rigid at her sides, while her lover has given way to (or metamorphosed into) the figure of Death, Death in torn chainmail with a proprietary white hand on her breast.

Does the second image represent the future or the facts beneath an idyllic fantasy? The surrealists juxtaposed images to subvert the rational consciousness and place a higher reality—a sur-réalité—above it. O’Grady wanted to return the image to the realm of private significance and signification, a sous-réalité in which there was space for the perspectives of excluded others.

O’Grady wanted to return the image to the realm of private significance and signification, a sous-réalité in which there was space for the perspectives of excluded others./pullquote]One such other was the Haitian emigrée Jeanne Duval, who was lover and companion to Charles Baudelaire for more than twenty years and whom O’Grady believed had been instrumental in the poet’s transformation from a late Romantic to the first Modern. She is, however, only a marginal presence in most biographies. O’Grady made a case for her centrality with a series of diptychs she called Studies for Flowers of Evil and Good (1995-1998).

In the first four of these, sketch-renderings of Duval and Baudelaire occupy facing panels, their faces layered with figures from Picasso’s Les Demoiselles D’Avignon, which seem to peer out from the couple’s features like the ghosts of unborn future children. Maybe they represent the fulfillment of the modernism that Baudelaire could only beckon toward, as well as the avidity with which white western artists exploited African (and “African”) imagery.

The poet’s panels are framed by extracts from Les Fleurs du Mal, in O’Grady’s translation. In Duval’s panels, the text is fictional: she left no written legacy, so O’Grady had to invent one for her. Evidently she repented of this: “I know that I am guilty as Charles. I, too, am using Jeanne.”

In the last four diptychs in the series, she replaced Jeanne’s image with photographs of her mother and female relatives. They, too, left the Caribbean for a cosmopolitan city, hoping to make a life for themselves.

By placing them in the lacuna left by Duval’s absence, O’Grady turned the speechless dialogue between Jeanne and Charles into a work of private significance and signification, a self-portrait of the artist as the child of four parents and two diasporas looking back at her origins.

One of the artist’s last performances was a collaboration with the musician Anohni, in a 2016 video for the song “Marrow. It’s on the Hopelessness album, and it’s about the end of the world. Technically, the piece is Anohni’s: The music is hers, the words are hers. It’s her prayerful and voluptuous countertenor. O’Grady, who was then eighty-one, is just lip-synching Anohni’s hymn of despoliation: Suck the marrow out of her bones….Suck the money out of her face.

But that aged face projects such intelligence and feeling—you can see the artist counting beats, gauging her entry, savoring the song’s lozenge of bitterness and beauty—that she becomes “Marrow’s” co-creator. The way she bites her lip before singing “We are all Americans now” signals that the sorrow is hers, too. She’s placed her claim on it. Lorraine O’Grady could never be anybody’s mouthpiece.

______________________________

The Twilight of Bohemia: Westbeth and the Last Artists in New York is available via Godine.

Peter Trachtenberg

Peter Trachtenberg was born and grew up in New York City and began spending time in Westbeth in the late 1970s. He lived there (illegally) from 1995 to 2006. He is the author of The Twilight of Bohemia: Westbeth and the Last Artists in New York, along with three earlier books of nonfiction, and he is the recipient of awards that include Whiting and Guggenheim Fellowships and a Phi Beta Kappa award.