A Beautiful, Sacred Thing: Megan Giddings on Going to the Movies To Invoke Anger

Or, Finding the Line Between Art and Entertainment

When we briefly agreed that yes, COVID should be taken seriously, one of the things I missed most was going to a movie theater. The only time I’ve actually related to Don Draper of Mad Men, is when Peggy says about Don, “He sees everything.” And that’s how I lived a big section of my creative life, going to the $5.50 matinees in one of the worst movie theaters in the world and seeing everything.

Sometimes, I try to make my moviegoing this beautiful, sacred thing. I’ve said before that it’s the closest I can get to mass, and in some ways, that’s true. I grew up very Catholic. I think mass is where I first learned the story structure that I tend to gravitate toward in my own writing. I see it in other writers’ work. It’s how I’ve always seen the structure of Jazz by Toni Morrison, a writer whose own Midwestern Catholicism clearly influenced her work.

You sing, the main characters for the day parade in, you sing again, you hear about the past, you hear about the closer past, the priest in his homily—if you’re lucky—might tie these two stories together in a way that makes you reflect—which if your book is working well is what the middle section of your novel does—and then you move to prayers and intentions or a slanted view of the world, the sign of peace (your characters converge), and the big event: the transubstantiation.

In front of you, ordinary wafers and wine are blessed and become something greater for the people to receive. And isn’t that what the ending of a novel should do? It doesn’t matter if you’re walking into magic, dealing with domestic dramas, or something thrillingly else, your job, depending on the kind of writer you are, is to take the accumulation of events and turn them into something sacred and communal that can be consumed and carried forward by the reader.

I think mass is where I first learned the story structure that I tend to gravitate toward in my own writing.

What I like about seeing movies is yes, occasionally I do feel that sacred communal feeling that art brings. One of the last movies I saw before the pandemic drove me mostly away from the theater was Greta Gerwig’s Little Women. It was before my first book came out, and despite myself, I was moved by the moment where Jo watches her book being made, where she advocates for herself. It’s the type of benevolent narcissism that art allows. Somehow, despite all the barriers and jumps in the way, there I am.

But there was also the joy of leaving the theater and walking behind a group of what seemed like mothers and daughters who were all friends. While one was quiet and contemplative, the rest were furious about the movie’s arrangement. “I had to keep thinking and figuring out where we were in time,” a woman said and she was delighted when everyone else agreed that it felt like a lot of work.

Sometimes, though, I choose movies just to be pissed off, because against my better judgment and the way I would like to see myself, anger is a necessary part of my writing process. I watch the dumbest, cruelest jokes in the world; I watch couples who look like they would rather eat a piece of pizza off the sidewalk than kiss each other try to tell me something about love or desire; I watch Anne Hathaway—who is supposedly a brilliant scientist—talk about the power of love rather than the actual question she was asked about gravity and time and safety. Yes, I am still grudge holding. And to the person who shushed me when I muttered, you have to be fucking kidding me, I remember you, too. That was a joke, not a threat.

The anger sustains me because it makes me indignant, because it makes me think melodramatic things like, I’ll show you what art is. It doesn’t even matter to me in those moments that I’m conflating art and entertainment. I understand intellectually that what I am trying to do as a writer is a mix of both, and that especially in filmmaking there’s a much stronger delineation between those two styles of creating. It feels like it’s becoming rare and harder to be someone in that field who can do both and be successful. Writers who care about art and care about entertainment have to perform our emotional dances in high heels, backwards, and saying here is the entertainment, while also somehow communicating grace and elegance that say, here, here, is your art.

It doesn’t even matter to me in those moments that I’m conflating art and entertainment. I understand intellectually that what I am trying to do as a writer is a mix of both.

So often, I’ve heard people say don’t write angry. I add to this that if you’re lucky enough to publish a book, and if you are double-lucky: you will go on a book tour and have to negotiate not just the complications of speaking in front of other people about something you care deeply about, but also having to talk about the things that upset you—all while sounding interesting and kind and engaging.

Another level of highwire performance and complications. Another reason to go to therapy if you can actually afford it. Another reason to wonder sometimes if when people say, “I am tired of books where Black people deal with trauma or the world as it is, why can’t they just live,” they’re also quietly saying, “I am tired of books by furious Black writers.” Even though to be alive today, to be paying attention and to want people to be treated well, is to find a way to live with a furious benevolence that you have to use to find a way to be kind to other people.

I’ve written two books now that at their root are about things I’m so angry about they could become poisonous to me. That’s what untamed anger does: it rots out your brain and dampens almost all other emotions so that you feel compelled to act or lash out. You keep finding more and more reasons to let your heart pound and your brain narrow in on the thing that set all this off and continually risk losing the best parts of yourself as you become further adrift in that rage.

Sometimes, when I re-read a draft, what leaps out first is always the bitterness. But I’ve gotten better at seeing the flowers and characters and world that spun out of it.

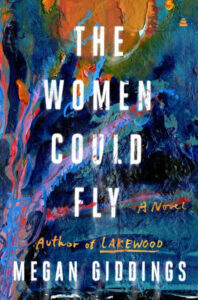

The pleasure and control I feel when I can take something that could break my creativity, harm my ability to connect and empathize with other people, to connect to myself and turn it into a story is what sustains me. Writing my novels Lakewood and The Women Could Fly didn’t cure my anger about the American healthcare system, systemic oppression of Black people, or the second-class humanity that the United States’ laws and policies inflicts on anyone who is not a cis, straight man.

But I keep writing through all of this. My moviegoing average is now an abysmal once a year. When I watch at home, I sit with my notebook on my lap, writing down the things that genuinely made me feel. It’s faster to get to my desk now, but I don’t feel as refreshed when I get there.

Sometimes, when I re-read a draft, what leaps out first is always the bitterness. But I’ve gotten better at seeing the flowers and characters and world that spun out of it. The terror and hope and frustrations. Everything I hate about me and the world is in my books, everything I love about me and the world is there. When reading is done well, when it’s closer to listening and wanting to hear what the other person, the writer, is saying, it can fortify you with bigger and more complicated thoughts. It can move you toward a more nuanced grasp of living if you’re willing.

______________________________

The Women Could Fly by Megan Giddings is available from Amistad

Megan Giddings

Megan Giddings is an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota. Her first novel, Lakewood, was one of New York Magazine's top ten books of 2020, an NPR Best Book of 2020, a Michigan Notable book for 2021, a finalist for two NAACP Image Awards, and was a finalist for an L.A. Times Book Prize in the Ray Bradbury Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Speculative category. Megan's writing has received funding and support from the Barbara Deming Foundation and Hedgebrook. She lives in the Midwest.