I get in the taxi at 900 Alem Avenue. I throw my purse and bag of clothes, the folder with my notes, and the envelope with the receipts on the seat. While I look for my gloves, I say, To Flores, the corner of Bilbao and Membrillar. Dumb name, Membrillar, frivolous. I imagine a hero addicted to cans of membrillo jam. Should I take Rivadavia or Independencia? I can’t find my gloves and am slow to answer. It doesn’t matter, take whatever you like. Independencia will get us there faster, señora. Señora? Did he just call me señora? I find the gloves, calm myself down, don’t answer. Señora, I’ll take Independencia, then. I still don’t answer.

I look around the taxi. An ashtray that’s empty, clean; a sign saying “Pay with Change” without the please or the thank you; a pink pacifier hanging from the rearview mirror; a dog with no dignity wagging its head, saying yes to everything, to everyone. The aura of static cleanliness, of calculated orderliness, exasperates me. I take off my gloves, look for my keys, put them in my coat pocket. Old age that’s covered up irritates me. I look out the window. I’m drowsy.

Do you mind if I put some music on, sweetheart? I look at the driver, disconcerted. When exactly did I go from señora to sweetheart? Was it the magnitude of 9 de Julio Avenue that led his brain to make faulty connections? Was it my pseudo-interest in his natural habitat that led him to abandon formality? I don’t mind, I answer. He puts cumbia on, and I do mind. I look at the driver’s information so I know the exact name to curse in my head. Pablo Unamuno. The irony surprises me. I never would have taken the bearer of so distinguished a last name for a cumbia enthusiast. I laugh at my idiotic elitism, then uncross my legs in an attempt to cover this up. I look at his photo. Either it was taken recently or Señor Unamuno uses the same formula for immortality on himself as he does on his car. It’s cold, but I imagine his shirt is open so it’s crystal clear he exercises, lifts weights, bags of cement, bags of receipts, notes, clothes, literary and philosophical theories. He stops at a light, glances at me in the mirror, smiles. He places his arm behind the passenger seat, and, hanging from his wrist, I see a gold bracelet with AMANDA on it. I suspect she’s the owner of the pacifier. If she was the mother of the owner of the pacifier, the bracelet would be hidden. Straight hair, ripped jeans, he’s confident this look is enough. I cross my legs. I’m bored by beauty that’s easy, saturated.

Then I see them. The lights from Juan Bautista Alberdi Avenue reflect off his nails—nails cut with the dedication granted only to the most valuable things. Unamuno’s arm is still resting on the passenger seat and I can directly examine the two layers of transparent nail polish applied with the patience of the obsessive, with the precision of the enlightened. We stop suddenly at another light and I move forward a little, confirming that his cuticles are impeccable. I feel a rush and open the window. What would Juan Bautista Alberdi have thought of all this? He wouldn’t have been able to understand that true genius is concentrated in mundane, banal details, not in treatises on diplomacy or erudite literature. He wouldn’t have caught the importance of the insignificant. I settle into the seat and close the window. The cold distracts me.

I think: Unamuno is concealing something with his nails. Their perfection can have been conceived only by a mind that’s distinct, superior. A mind capable of crossing limits, of exploring new dimensions. I reckon: Unamuno’s secret is hidden in a space that’s familiar, quotidian. He requires constant contact with his object of pleasure. I surmise: the taxi is his inner world. He alone has unlimited access. It provides him with the privacy and daily interaction he requires. Where could his secrets be? Under the seat? No, too complicated. In the glove compartment? Yes. It’s the perfect spot for secrets. Behind the car manual, he keeps clippers, nail polish, cotton, and two boxes that are transparent, impeccable. In one, he collects his nails as an example of the sublime. In the other, the perfectible nails of his victims. Yes, Señor Juan Bautista, Unamuno is a serial killer.

I unbutton my coat. I elaborate: He’s not just any serial killer, one who’s numerical, expansive, inclusive, ordinary. Don’t pay Unamuno the attention he’s due, and he’ll pass for a person with no great aspirations. Of course, you need to know how to look, because he leads a life that’s consistent, if alarming. He’s patient. Selective. Ascetic. He’s dangerous. The pacifier is a planned diversion for those who don’t know, for those who don’t want to know. The docile dog is a false manifestation of an existence that’s trivial, resigned. I infer that the AMANDA bracelet belonged to his first victim. A woman who looked dejected, but young. Disoriented and alone. Unable to resist; therefore, easy. Her long nails red and unkempt.

Unamuno didn’t settle for immediate gratification. He didn’t rape her in the taxi and throw her into a ditch. No. He carried out a ritual.

Without knowing how it happened, Amanda found that she was naked. She couldn’t move, or talk, but she was completely conscious. Unamuno bathed her in jasmine water, wrapped her in a towel to dry her off, put a clean dress on her, made her up, dried her hair very slowly, combing it with his fingers, perfumed her, left her on the bed, and took off his clothes. But before this, he allowed an unexpected cello to envelop them in the merciless serenity of Bach’s Suite No. 1 in G Major. Naked, he filed her nails, caressed them, cut her cuticles, removed the polish, cleaned them with warm water, kissed them, applied a strengthening coat, put mint-scented lotion on them, massaged it into her hands, placed them on a clean towel, and painted her nails with two layers of red polish. When he was finished, he rested her hands on his naked body, waiting for the polish to dry. Throughout the process, from within her immobility, Amanda understood she was going to die a strange and useless death. Still, she couldn’t avoid feeling that it was right, because it was careful, pleasant, thorough, gentle. Unamuno made sure she felt a serene freedom, a sharp freshness. After she died, he cut her nails with a dedication bordering on devotion and put them in one of the transparent boxes.

Excuse me, sweetheart, can you tell me where to turn onto Bilbao? I settle back into the seat, open the window, button up my coat, and tell him. I cross my legs. Breathe. Try to calm myself down. I look out the window to stop thinking, but I can’t. I look at my nails. They’re long, unkempt. I think about Amanda and ask, Is that your daughter’s pacifier? Unamuno coughs, turns off the radio, looks surprised. We stop at a light and he avoids my question by crouching down and opening the glove compartment. I lean forward and all I see are papers and rags. I feel like an idiot. I want to yank the head off the disciplined dog, the dog incapable of saying no. I put my gloves on angrily. I curse the cumbia, the nails, the taxi, and Unamuno’s awful simplicity.

How much do I owe you? One eighty-four. I decide to pay with exact change, to punish him for his healthy mind, his lawful life, his clean hands. I gather my bags, grab my keys, open the door. What I want is for him to wait, to exercise the serial killer patience he never developed. I take off my gloves and put them in my purse. I look for my wallet, take out the change, and count it. I take out the bills, count them. As I hand him the money, a coin falls into the space between the two front seats, a space that I realize also contains a box with a lid. Unamuno takes off the lid to look for the coin. He takes it off fully and he takes it off slowly. He looks at me. Smiles. For a second I freeze. Then I’m able to breathe, and I lean forward to see clippers, nail polish, cotton, and two transparent boxes. Suddenly, I close the taxi door, grab his arm, move closer, and say: Let’s go, Unamuno. Take me with you, you know where.

__________________________________

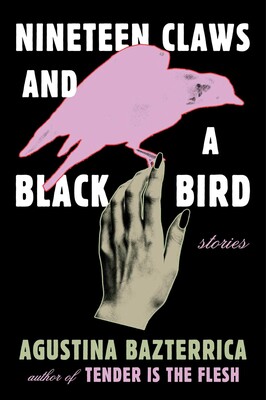

Excerpted from NINETEEN CLAWS AND A BLACK BIRD by Agustina Bazterrica. Copyright © 2020 by Agustina Bazterrica. English language translation copyright © 2023 by Sarah Moses. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.