9 Must-Reads for Lovers (and Haters) of The Last of Us

From the Science of Fungi to the Collapse of Civilization, a Book For Everyone!

The Last of Us—HBO’s star-studded adaptation of the VERY popular video game of the same name—has been a huge hit. Whether or not you think it veers too far from the game (or hews too close, or is politically compromised), you’ve probably kept watching it, week in, week out.

The story itself is not an unfamiliar one: for vaguely plausible “scientific” reasons a zombie plague has swept the globe, leaving the human survivors to sort through the horror and chaos of post-civilization reality; varying levels of authoritarianism and anarchy ensue.

Both the game (which I have played) and the show are reasonably thoughtful in their dedication to moral ambiguity, dispensing with any semblance of the traditional hero/villain dichotomy (at least so far as humans are concerned). Sure, some people are much kinder and more decent than others, but even the worst, most morally compromised characters are allowed glimmers of humanity.

A large part of the adaptation’s success is due to the strength of its lead actors, Pedro Pascal (Joel) and Bella Ramsey (Ellie), who manage the necessary balance between pragmatic stoicism and deeply wounded vulnerability.

Oddly enough, in both the game and the show, the zombies are kind of beside the point; they are the reason for the post-apocalyptic hellscape, but they could just as well be a catastrophic weather event or a swarm of AI bots-gone-wild. The Last of Us is a well-told story about people and the things they’ll do for each other (and to each other) when all else seems lost.

For a TV adaptation of a video game, there’s an awful lot going on in The Last of Us, and in many ways the show is smarter, and goes deeper, than the game. If you’re already worried about withdrawal (the season finale airs this Sunday, March 12), and you’d like to read a bit deeper into some of the ideas behind The Last of Us—the science, the atmosphere, the moral underpinnings—here’re some books to keep you occupied until season two.

*

Suzanne Simard, Finding the Mother Tree

Those vaguely plausible “scientific reasons” I mentioned above? In The Last of Us, increased global temperatures have made it possible for the notorious “zombie” fungus, cordyceps (a real-life parasitic fungus that can take over insects) to survive in humans. That’s bad. And get this, as the fungus spreads through humanity it creates massive subterranean mycorrhizal networks that “communicate” from zombie to zombie.

Just like trees!

For more on that, I highly recommend Suzanne Simard’s utterly engrossing memoir of unlikely scientific discovery as she works tirelessly—in the face of overwhelming doubt and unexamined convention—to prove that trees communicate through a highly sophisticated underground filigree of fungal connections. Finding the Mother Tree will shift your perspective on forest ecosystems, and provides further evidence of the myriad and mysterious connections between all living things (nice for the trees, but bad if you have a zombie problem).

Cal Flyn, Islands of Abandonment

A worldwide zombie apocalypse is not great for civilization and all the spaces it has created: malls, central business districts, theme parks, college campuses… these are not good places to be when 99 percent of the people you once knew want to eat you.

Islands of Abandonment is a fascinating series of post-human case studies, in-depth looks at abandoned spaces and the people who dare live there. Whether through environmental destruction (volcanic eruptions), man-made disasters (Chernobyl), or political hostility (the Korean DMZ), these places are more resilient than we think. Though Flyn’s book is a true catalog of worst-case scenarios, it also offers something like hope that life can go on even in the face of the unimaginable. (There is a scene in the game version of The Last of Us in which Ellie encounters a herd of giraffes in downtown Denver; it could very much be plucked from Islands of Abandonment.)

Merlin Sheldrake, Entangled Life

More so in the game than the show, The Last of Us contains some eerily beautiful renderings of fungal life, as once-human zombies gestate in a state of fallow overgrowth, gradually becoming more mushroom than humanoid. While The Mother Tree focuses on the mycorrhizal networks that enable underground communication, Sheldrake’s wide-ranging, near-obsessive look at fungi in all its iterations—including the infamous cordyceps—is perfect for anyone secretly rooting for the mushroom zombies.

Cormac McCarthy, The Road

If Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven is at the hopeful end of the “one adult/one child post-apocalyptic quest” genre than The Road is at the other (The Last of Us is somewhere in the middle, leaning a little bit to The Road.) No zombies are necessary for McCarthy’s grim and hopeless End Times though: human desperation, and the depravity it engenders, provide horror enough.

Andrew Krivak, The Bear

Not enough people have read this achingly beautiful novel about the last man on earth and the final journey he takes with his daughter to the sea. Told as a mesmerizing fable, with all the poetry and none of the sentimentality, The Bear comes to terms quickly with its own premise: someday, we too, will go extinct, and all of human history will blink out as our distant descendant, our endling, takes her last breath.

John “Lofty” Wiseman, The SAS Survival Handbook

One of the “fun” parts about playing The Last of Us is the way it gestures to the inevitable scarcity of actual post-apocalyptic existence. You can’t just keep mashing a button and shooting zombies, you actually need to think about your resources—both health and ammunition—to survive. And what’s more satisfying than having a series of little digital to-do lists to cross off? (This is one of several reasons episode three, starring Nick Offerman as an aging survivalist, is among the most popular of the season.) So if you haven’t already, why not get in touch with your inner prepper and cross-check your bug-out bag with The SAS Survival Handbook, the UK’s go-to for when they run out of turnips.

Christopher Isherwood, A Single Man

Back to that third episode, one of the best hours of TV to air in a long while. Nick Offerman plays a conspiracy-addled survivalist named Bill whose cultivated paranoia has left him nonetheless prepared for the fungal zombie apocalypse. Because of all his preparations, Bill is able to create a sustainable “clean zone” around his small-town neighborhood, where he expects to live out his life alone—and safe—from the hordes beyond the fenceline. One day, though, he discovers a man caught in one of his traps.

Despite the near manic levels of caution that have allowed him to survive this long Bill brings the man, named Frank, home and feeds him dinner. What follows is a beautifully told queer love story spanning decades, filled with the kind of tenderness and lived detail you would not expect from the tv adaptation of a zombie video game.

Even today there are not a lot of mainstream stories of queer aging, and the quiet but deeply felt love between the two characters calls to mind Christopher Isherwood’s classic of middle-aged gay love, A Single Man. (Not least because the doom that hangs over every scene in The Last of Us casts a shadow of grief over even the happiest moments—and if anything, A Single Man is about grief). Though Isherwood’s novel is the story of a lover left alone by death (unlike Bill and Frank), its melancholy tenderness and afterglow of devotion maps neatly over episode three’s achingly beautiful apocalyptic gay zombie love story.

David Graeber, Pirate Enlightenment, Or the Real Libertalia

Sure, mushroom-headed zombies are scary, but have you seen what happens to people when society collapses around them? For the creators of The Last of Us, the power vacuum that follows the disintegration of civilization is inevitably filled by authoritarianism, warlordism, and violent zealotry—all the worst aspects of humanity organized into roving militias of varying ideological coherence.

But what if that descent into might-is-right savagery wasn’t inevitable? For the late David Graeber, everyone’s favorite anarchist anthropologist, it wasn’t. In the posthumously published Pirate Enlightenment—based in his early fieldwork in Madagascar—Graeber introduces us to a version of libertarian direct democracy practiced by 17th-century Malagasy pirates. And guess what? It’s possible to dabble in self-governance without killing everyone who doesn’t look like you! Furthermore, many of the fluid versions of society dreamed up these Malagasy pirate communities anticipate later European attempts to build just and equitable social structures. Read this if you need a counterbalance to the societal collapse in The Last of Us.

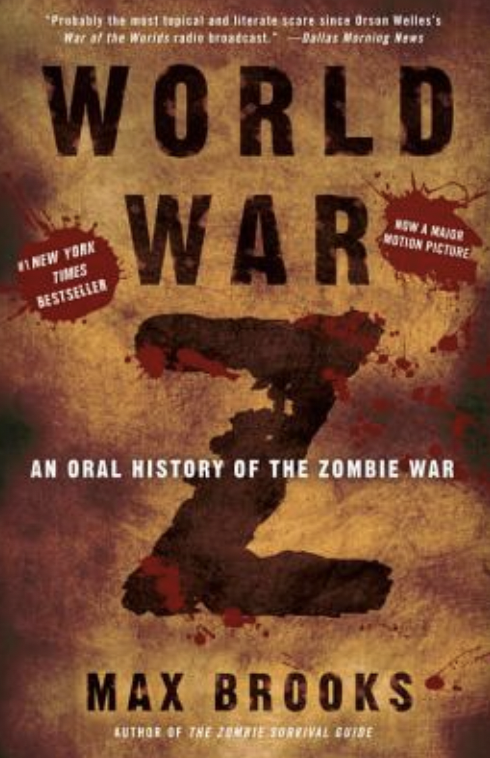

Max Brooks, World War Z

As you’ve probably figured out by now, I don’t think The Last of Us is really about the zombies, but if you’re desperate for stories of the undead—and what a zombie plague would mean for the future of civilization—you could do worse than Max Brooks’s modern classic of the genre, World War Z. As zombies multiply from a patient zero somewhere in China, the wold scrambles to salvage some semblance of civilization, fighting desperate rearguard actions, often sacrificing millions of citizens in order to save mere thousands. It’s a bit like reading about a giant game of zombie Risk.

Jonny Diamond

Jonny Diamond is the Editor in Chief of Literary Hub. He lives in the foothills of the Catskill Mountains with his wife and two sons, and is currently writing a cultural history of the axe for W.W. Norton. @JonnyDiamond, JonnyDiamond.me