81 Writers on the Books They Loved in 2021

From Contributors to Freeman's

Two years and running. The changed world in which we’re living has stayed altered, and in 2021 the quiet of lockdowns was exchanged for different silences—of mourning; of a steady, grinding maintenance; and in many cases, that hush which falls upon a reader. The solitude of two afforded by a book has not been more starkly felt by many in a long time. 2021 was the year readers went back to their shelves, having binged out of various tv shows. Bookstores were open in some places, and books could be given as gifts again, hand to hand. There are not many causes for hopefulness, but a year in which Abdulrazak Gurnah won the Nobel Prize, and books were the opposite of hot, but felt, loved and dove into in the idiosyncratic, passionate ways readers burrow feels like a small consolation in sick times. Every December I ask the contributors to Freeman’s what they loved, what struck them over the year: this year was the swiftest, most voluminous response yet, with dispatches coming from writers in Pakistan, Japan, France and USA, among many other places. May you get lost in what they found. –John Freeman, editor, Freeman’s

*

Graham Greene, The Heart of the Matter

(Penguin Group)

Supply chain disruptions have hit Karachi: we’ve been contending with inflation, shortages across the board. The price of onions, lentils and rice have been on an upward trajectory. One of my staples, Graham Greene’s The Heart of the Matter, a novel that I reread whenever I feel down, hasn’t been on the shelves for a year—I lent mine to somebody for some forgotten reason some time ago. A fellow at a commercial bookshop in my neighborhood told me, “No Greenes coming.” As it so happens, neither are my two novels.

Trawling secondhand bookshops double-masked a fortnight ago, however, I finally came across a worn paperback copy Greene’s opus for the price of a dozen eggs. It was like happening across an old friend: “Scobie… turned…along the shaded…corridor to his room: a table, two kitchen chairs, a cupboard, some rusty handcuffs…a filing cabinet: to a stranger it would have appeared a bare uncomfortable room but to Scobie it was home. Other men slowly build up the sense of home by accumulation—a new picture…paperweight, the ashtray bought for a forgotten reason on a forgotten holiday; Scobie built his home by a process of reduction.”

It’s as if no matter how difficult things get, Scobie, a British police officer posted in a country that resembles Sierra Leone during WWII, has it worse. He is a good man, exemplary even, but he slips once, only once, causing him to hurtle into certain oblivion. It has to do with a matter of the heart, and it always hits me like a punch to the gut. As I approach the end, I find I’m rationing: I read a page or two at night. I don’t want to go hungry. –HM Naqvi, author of Home Boy and The Selected Works of Abdullah the Cossack

Remica Bingham-Risher, Starlight & Error

(Diode Editions)

Some poets blossom in tender increments. Quietly. Privately. They are about the word, and they don’t even wait for fame, because that doesn’t matter. The word is what matters—not even “the work,” a phrase which assumes publication and all that comes afterward. Remica Bingham-Risher is one of those poets, and one of the best kept secrets of African American poetry. She’s greatly beloved both for her incredible poetry, and for her kindness and humanity, which shines through on the page. But (as the kids can say) don’t get it twisted: there are plenty of depths to Bingham-Risher’s poetry—and craft, and music, and surprising turns of language—as in her book, Starlight & Error, which is about realistic familial affection. Sometimes, the realism turns into the most shocking of Blues. Like with “Cleaning House,” about the speaker’s aunt, who stabs her husband for cheating with a lives-down-the-street woman who was considered a friend to that aunt. You’ll gasp, but give a satisfied, “Um,” when you come to the last line of this poem. I won’t spoil it for you. Go on ahead and buy the book. –Honorée Fanonne Jeffers, author of The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois and The Age of Phillis

Dave Eggers, The Every

(McSweeney’s)

Sometimes, love for a novel comes easy—you turn the pages, you fall in love, and then you tell everyone how hard and fast you’ve fallen. At other times, it comes rather more circuitously. For me, The Every is such a book. The first thing I will say about it is that I finished it. I looked at it and thought I’d never get through it, but then I did, and in these times of pandemic-induced ADHD, that is no small thing. After finishing it, I started a long argument with it that has continued to this day. Why was the revolution so individual? Why did the main character not have any friends, or family, or any sex, for that matter? Not even a kiss. 600 pages without a single snog.

But the arguments meant that the book lingered in my mind, which is why I am talking about it now. It is clever and prescient and angry, all things I love in a novel. It rages against all the ills in the world, a comprehensive rant about late-capitalism that encompasses everything from the death of journalism to the human appetite for surveillance. It is set in the near future, and when it describes our present, it refers to “the pandemics”—which at first annoyed me, because it means we are only at the start of a series of really terrible events, but since I read it, Omicron has reared its ugly head, and so I must confess, I did not love this book, but now I do, because it tells me something about my life that I didn’t know before, even if that news is very, very bad. –Tahmima Anam, author of The Startup Wife

Samuel Richardson, Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady

(Penguin Group)

Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa, published in 1748, has long been a gap in my literary education. I avoided it not just because it remains (I think) the longest novel written in English, but also because Richardson’s earlier novel, Pamela, an epistolary tale of a young servant girl desperately eluding her employer’s attempts to rape her, ends with Pamela discovering that she is in love with her “master” and happily marrying into the aristocracy. Blech.

Clarissa is a brutal inversion of that story, and the fact that it was written by the same author is fascinating in itself. Also epistolary, it tells the story of a young woman determined not to marry the dolt her family has chosen for her husband. Her parents imprison her in her home; she escapes; and from there the story becomes ever more harrowing, unforgiving and extreme. In the end, Clarissa is a graphic study of the pathologies endemic to a culture that treats women as property. It’s also a passionate celebration of female friendship and of the written word—storytelling as means of power and transcendence. (There is also a superb audio recording by Naxos with multiple readers) –Jennifer Egan’s new novel, The Candy House, will be published in 2022.

Ruth Ozeki, A Tale for the Time Being

(Penguin Books)

I’m late to the Ruth Ozeki party but now I’m dancing hard. A Tale for the Time Being is a confrontational yet tender novel, the narrative makes the reader work and stretch and think about the way they tell their own stories. Each of its facets is perfectly cut—a teenage girl in Japan, a writer in Canada, Buddhism, the oceans, the inheritances we both keep and throw away—and the whole glimmers and glitters. I’ve given away quite a few copies of a A Tale for the Time Being over this pandemic; I think it creates a moment to laugh or think or just exhale. –Nadifa Mohamed, author of The Fortune Men

Zadie Smith, The Wife of Willesden

(Hamish Hamilton)

The Wife of Willesden by Zadie Smith is a play rather than a novel, but I’m reading it carefully after watching a performance of it at the Kiln Theatre London. It’s a bawdy, punky reworking of Chaucer’s The Wife of Bath and I love the ‘London-ness’ of it. Sexy Alvita regales the locals of a pub with the gory details of her five marriages, to a soundtrack of disco, RnB and soul. It’s crammed with references to the original work but also Greek myths, Jamaican folklore and the story of London itself. Smith has a wonderful ear for dialogue and vernacular and in The Wife of Willesden it takes centre stage. –Nadifa Mohamed, author of The Fortune Men

Maggie O’Farrell, I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes With Death

(Vintage)

After being absolutely blown away by Hamnet, I went in search of more Maggie O’Farrell and was duly rewarded by her stunning memoir I Am, I Am, I Am: Seventeen Brushes With Death, which isn’t nearly as well known here in America. It should be. –Richard Russo, author of Chances Are…and Empire Falls.

Georgi Gospodinov, Time Shelter

(Liveright)

I recently read another book by Georgi Gospodinov, this one titled Time Shelter (it’s translated into English by Angela Rodel). It’s the most exquisite kind of literature, on our perception of time and its passing, written in a masterful and totally unpredictable style. Each page comes as a surprise, so that you never know where the author is going to take you next. I’ve put it on a special shelf in my library that I reserve for books that can never be fully exhausted—books that demand to be revisited every now and then. –Olga Tokarczuk, Nobel Prize-winning author of The Books of Jacob, translated by Jennifer Croft, out now from Fitzcarraldo Editions and forthcoming in the US in 2022 from Riverhead.

Teju Cole, Golden Apple of the Sun

(Perimeter Books)

Golden Apple of the Sun by Teju Cole is a book about hunger, the most ancient of our conditions. It opens with photographs of the author’s kitchen counter in Cambridge, MA. It’s Covid-19 pandemic and home cooking is having a moment. Unlike the traditional Dutch still lifes, these photographs don’t conjure up great hunts and feasts. Except for crumbs, spills, and a couple of lemons and limes, the plates are empty, and I almost expect to see my own reflection as I examine the polished surfaces of pans and spoons. The photographs are interspersed with an anonymous handwritten 18th-century cookbook from Cambridge. Cole muses that it might have been written by an enslaved woman. But it is Cole’s own essay, printed on thick, textured brown paper at the end of the book, that offers the most illuminating recipe. The list of ingredients is long: hunger, history, slavery, art, intimacy, mourning, home, trauma, poetry. Cole’s handling of them is elegant and discerning.

Reading this essay, I wonder whether the most important juxtaposition here is not between the photographs and the text but between the objects of daily use often found in the kitchens and the histories of consumptions, which are always the histories of power. Leafing through the photographs of Cole’s mixing spoons and cutlery, I arrive at the image of the 19th century Dutch salt spoon, “for which the scholarship is typically reticent.” This slim object, older than any of us and with the power to outlive all of us, exists because Dutch ships brought salt to Europe from Bonaire, the “paradise” where enslaved people harvested salt in unspeakable conditions, their blistered feet lowered into salt from dawn to dusk. Suddenly, the most boring item on display at the MET appears to us as the most frightening. Look how cold-blooded its silver shine is. Cole’s searching prose is crystal clear. I think of the 20th century Polish poets who wrote powerfully about the value of the day-to-day objects during the war and hunger. Golden Apple of the Sun is in good company on my desk. –Valzhyna Mort, author of Music for the Dead and Resurrected, and translator most recently, of Air Raid, poems from the Russian by Polina Barskova.

Can Xue, The Last Lover

(Yale University Press)

Reading The Last Lover by Can Xue is like a magical journey. The story asked me to wander through the characters’ experiences. We are in their books, dreams, and even hallucinations. I feel like flying without smoke anything. –Eka Kurniawan, author of Kitchen Curse: Stories, translated by Annie Tucker

Kazuo Ishiguro, Klara and the Sun

(Knopf)

In the spring, I read Klara and the Sun by Kazuo Ishiguro aloud to my eight-month-old daughter while pregnant with my son. The book’s chapter to chapter plotting made me feel as if I sat down at a magnificently laid table and only towards the end of the meal would I get to know what that special fork was for. I looked into my daughter’s happy little face, her eyes just waking up to every sound and color and I was grateful that she still had years to go before she could understand which words moved me to tears. In a time when I had been so focused on new beginnings, I was not expecting to leave the book thinking about aging loved ones who can no longer communicate. That month the world was just opening up again, and somehow all of life floated to the surface for me in this book, as if in preparation. –Xuan Juliana Wang, author of Home Remedies: Stories

E.J. Koh, The Magical Language of Others

(Tin House Books)

So many things to love in 2021! But my favorite is the way that E.J. Koh uses translation as its own vehicle for poetry in The Magical Language of Others—it becomes a gateway to a third language that spans the distance between two writers. I often think of the translation of the words, I miss you. Translated into Korean it is 보고 싶어요 bogoshipoyo. Translating 보고 싶어요 bogoshipoyo back to English, it is I want to see you, and this journey through translation offers us new words / new stories / new poems: a sense of yearning that comes with a body. Even Korean can be translated into Korean and even English can be translated into English. I miss you also means When I am here you are not here. Throughout the book, the translations (sometimes blunt and ungraceful, sometimes sweet and easy) mimic the distance between Koh and her mother, and later, their fluency. This magic of language—of ours and of others—is precisely the poetry I adore. –Christy NaMee Eriksen is a multidisciplinary writer and producer of the poetry album How to Tell if a Korean Woman Loves You

Bette Howland, W-3: A Memoir

(Public Space Books)

2021—what a year, spent entirely in a pandemic. The only bright spot is that I’ve read more books than any other year, and the list of books that I’ve loved this year will be running around the block. From the list, two books published this year have launched me into two intense writing projects, so I feel particularly indebted to them. W-3 by Bette Howland is a touching and thought-provoking memoir about Howland’s experience of a mental breakdown and hospitalization; after attending an event where her two adult sons, who were both young children in the memoir, discussed her life and work, I was inspired to begin a new novel, right the next morning. –Yiyun Li is the author of Tolstoy Together: 85 Days of War and Peace with Yiyun Li.

Elizabeth McCracken, The Souvenir Museum

(Ecco Press)

The Souvenir Museum by Elizabeth McCracken is a collection of superb stories; they are bittersweet, happysad, unforgettable, inexplicable, and they mesmerized me in such a manner that after reading the collection, I wrote three new stories in a month. –Yiyun Li is the author of Tolstoy Together: 85 Days of War and Peace with Yiyun Li.

Benjamín Labatut, When We Cease to Understand the World

(New York Review of Books)

By far the most arresting book I’ve read this year is Benjamín Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World (tr. from the Spanish by Adrian Nathan West). In a dreamlike narrative style that often recalls W. G. Sebald—whom Labatut cites as an influence—the author weaves together tales of scientists and their discoveries with larger tales from the last century’s traumatic history in an unforgettably suggestive way. That the eighteenth-century quest to create a man-made blue pigment should have led inextricably to the development of the poison used to murder Hitler’s victims is just one of the astonishing revelations of this idiosyncratic and brilliant work. –Daniel Mendelsohn is the author, most recently, of Three Rings: A Tale of Exile, Narrative and Fate. His new translation of The Odyssey will be published in 2022.

Steven Millhauser, Voices in the Night

(Vintage)

Reading Voices in the Night by Steven Millhauser left me feeling both dazzled and nostalgic for another time. It felt like I was peering through a powerful lens, observing the minutiae of human life (and afterlife) from some distant, unknown place. This is a story collection that I will be returning to again and again. –Sayaka Murata, author of Earthlings and Life Ceremony: Stories, forthcoming from Black Cat in 2022, both translated from the Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori. Citation translated by David Karashima.

Etel Adnan, Paris, When It’s Naked

(Post Apollo Press)

Etel Adnan’s Paris, When It’s Naked, came to me at just the right time. I’d landed in Paris for a fellowship some weeks earlier, along with my dog, and the city seemed to be constantly weeping—unrelenting rain. Etel, who had lived in Paris for the last thirty years at least, and up until her death last month, knew the city in the minutiae. She never owned a pet, but writes—with empathy and humor—about the “courageous citizens” who still had to walk their dogs in rain (an experience new to my dog and me, neither of us too happy about it). Beyond this recurring observation she has of the duties of dog-owners who she seems to pity, the book is a beautiful, thoughtful rumination on a city she came to call home despite the complicated relationship she had to its political history and language. “Why am I living in Paris,” she asks in one chapter. “Because I speak French? That could be a major reason, but it’s not”. Somehow through her words and wisdom, and her eye that missed nothing in the city with it’s often estranging ways, the book offered me a field-guide of sorts, on how to inhabit Paris temporarily, and even find some humor in its downpours. –Yasmine El Rashidi, author of Chronicle of a Last Summer

Stephanie Dickinson, Blue Swan Black Swan: The Trakl Diaries

(Bitter Oleander Press)

My bookshelf stutters with multiple copies of things because I’m a sloppy reader and I don’t keep an inventory. Sometimes people send me books. Sometimes I’m hoodwinked by a new cover or seduced by a new translation. They pile up like shelled sunflower seeds on the floor around wherever I’ve been sitting. It’s not uncommon for me to find a book on my desk and have no idea how it got there. Such is the case with Stephanie Dickinson’s Blue Swan Black Swan: The Trakl Diaries. Did I order it because the lyricism is intense, psychedelic and dark? Did someone send it to me knowing I’d go gaga over the intertextual form in which Dickinson’s short prose/ poems respond to quotations lifted from accounts of George Trakl’s brief and wretched life? Whatever brought us together is irrelevant now. I have it and it has me and unlike my glasses, I can tell you exactly where I set it down last. –Gregory Pardlo, Pulitzer Prize winning author of Air Traffic and Spectral Evidence: Poems, forthcoming from Alfred A. Knopf in 2022

Brigitte Reimann, tr. Lucy Jones, I Have No Regrets: Diaries, 1955-1963

(Seagull Books)

Mid-November, a friend sent me a very beautiful surprise present: Brigitte Reimann’s I Have No Regrets. I started reading it immediately. I’ve never read a book similar to this in my entire life, revealing a mixture of shyness, fragility, passion and boldness. It mounts to almost a literary lesson on how the most fragile are entitled to live life to the fullest. –Adania Shibli, author of Minor Detail, translated from the Arabic by Elisabeth Jaquette

Roberto Calasso, The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony

(Vintage)

Maybe it was the cover. Maybe the cover is why I picked up The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony. It is Romain’s “Pandora Descending to Earth with Mercury,” and yes, she is holding the box. Maybe it was the box that drew me? Regardless, Greek mythology, with its finical and flaming gods—toying with us and sleeping with us and waging war with us and then abandoning us—maybe these gods, above all others, could make sense of the times. And in Calasso’s masterful retellings, they do, but not in the way I’d anticipated. Quite by surprise, in the way the best of literature surprises, I realized, on the last page, that the gods make us suffer and wail and want and weep because, ultimately, what they want is exactly what we want: a good story. –Shobha Rao, author of Girls Burn Brighter

Caleb Azumah Nelson, Open Water

(Black Cat)

2021 is the year I truly surrendered to reading. What else was there apart from the continued battle with the virus infested world? I want to shout out loud for a debut novel—Open Water by Caleb Azumah Nelson. I was deeply impressed by its exquisite prose. It is a subtle but powerful portrait of the realities of race today in Britain, and a very tender, sensual story celebrating youth and romantic love by a young male author. The portrait of urban masculinity in this small book is nuanced and fascinating. I also want to raise my voice for another work, a translation. I was totally absorbed by the French author Nathalie Léger’s trilogy about three real life women figures. I especially loved her Suite for Barbara Loden, translated by Natasha Lehrer and Cécile Menon. The book is a retelling of the scenes in the cult film Wanda directed by the 60s American actress Barbara Loden. It interweaves episodes of Loden’s life with Elia Kazan and Hollywood, as well as Léger’s own personal history. The result is a rich, layered narrative. Again, it is a very small book with large themes. It had a forceful Duras-esque effect on me. It reveals to us the possibilities of autofiction, an overused word but nevertheless an inescapable concept in our storytelling lives. –Xialou Guo, author of many books, including A Lover’s Discourse

E. M. Forster, Maurice

(W. W. Norton & Company)

This year I was drawn back into re-reading Maurice, by E. M. Forster, and after a third re-read and a first read of Wendy Moffat’s biography of Forster, A Great Unrecorded History, I wrote about Maurice, Forster and the new novel Alec, by William di Canzio—his continuation of Maurice from Scudder’s POV—for The New Republic. And then I just kept at the Forster, re-reading Howard’s End and A Passage to India for good measure. There’s a way Forster can write so devastatingly and yet lovingly about people who aren’t aware of themselves. –Alexander Chee, author of How to Read an Autobiographical Novel: Essays

David Plante, Difficult Women

(New York Review of Books)

I also read David Plante’s Difficult Women, a haunting account of his friendships with Jean Rhys, Sonia Orwell and Germaine Greer, and the new translation by Rachel Careau of Colette’s Cheri and the End of Cheri, coming out from Norton next year. And a lot of what I loved of what I read recently is for next year, like three fantastic debut novels: Alejandro Varela’s The Town of Babylon, Joseph Han’s Nuclear Family, and Sequoia Nagamatsu’s How High We Go In The Dark. And at this very moment, I’m riveted by Maud Newton’s forthcoming nonfiction book Ancestor Trouble, on what she discovered about white supremacy while examining her family’s legends. –Alexander Chee, author of How to Read an Autobiographical Novel: Essays

Geoffrey Wellum, First Light

(Penguin UK)

This ended up being the year of reading Elizabeth Taylor—seven of her twelve novels, all of them, so far, of stunningly high quality. Before that it was the summer of books about the Battle of Britain. Stephen Bungay’s The Greatest Enemy, is, I think, the best overall historical account. Richard Hillary’s The Last Enemy is the iconic pilot’s memoir, detailing his idyllic undergraduate and flying days and then the slow, agonizing and partial recovery from hideous burns after being shot down over the English Channel. But the book that made the deepest impression, strangely, didn’t have enemy in the title at all! Geoffrey Wellum’s First Light covers both the Battle of Britain and subsequent sorties flown in the war.

It is written without any of the literary ambition that actually works to Hillary’s detriment and, perhaps because of that, achieves a remarkable immediacy. It is also very moving. One of the later episodes in the book involves Wellum’s role in the mission to fly planes and supplies to the besieged island of Malta. An account of the whole perilous undertaking is given by Max Hastings in his latest—and thoroughly gripping—installment of Second World War history, Operation Pedestal. –Geoff Dyer, author of twenty books including The Last Days of Roger Federer: And Other Endings, forthcoming in 2022 from Farrar, Straus & Giroux and Canongate Books

Vilém Flusser, Vampyrotheuthis Infernalis: A Treatise

(University of Minnesota Press)

I’ve become fascinated with the philosophic work of Vilém Flusser, a Czech Brazilian, who escaping the Holocaust in 1940, immigrated to Brazil, then with the rise of the military dictatorship, left for Europe again in the 1970s. My interest began with what he called, a fabula: Vampyrotheuthis Infernalis: A Treatise, with a report by the Institut Scientifique de Recherche Paranaturaliste, by Louis Bec and Vilém Flusser, originally published in 1987. It’s a philosophical and, I believe, Borgesian fable about the vampire squid from hell, our human physical, intellectual, and psychological opposite, living in the deep abyss of the ocean. What bifurcates our existence also joins us. A fabula for the anthrobscene. –Karen Tei Yamashita, author of many books including, most recently, Sansei and Sensibility: Stories

Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five

(Modern Library)

I read quite a few books in 2021, but if I had to pick one that stuck with me it was rereading Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse-Five. Deep into Vonnegut’s sci-fi masterpiece about the bombing of Dresden in World War II, you realize the heart of the book isn’t sci-fi at all, and that it’s not really about Dresden. It’s about the existential angst of the “Greatest Generation,” and the emptiness of white suburbia and all the totems of white achievement, and all the traumas hidden inside the lives of a seemingly comfortable and affluent people. –Héctor Tobar, author of Deep Down Dark and The Last Great Road Bum

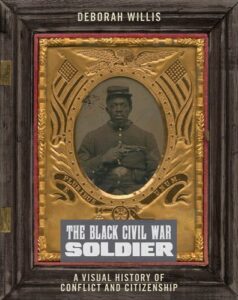

Deb Willis, The Black Civil War Soldier: A Visual History of Conflict

(New York University Press)

The legendary photographer, curator, and historian Deb Willis has been shifting the way I see and think of images and historical representation for decades. The Black Civil War Soldier: A Visual History of Conflict, her gorgeous and meticulously researched photobook, is expansive, yet it also manages to convey the intimacy of a beloved family heirloom. It is an impassioned tribute to America’s Black soldiers and their families during the Civil War. It is also an insistence that we consider the many ramifications of conflict and racism. This is a monumental work, as well as a monument to the undying quest for freedom. –Maaza Mengiste, author of The Shadow King, shortlisted for the Booker Prize

Colm Tóibín, The Testament of Mary

(Scribner)

Mary is an enigmatic figure. Devalued in the Protestant tradition, revered as a saint in Catholicism, exalted as the mother of a prophet in Islam, she is one of the most wordless figures in history. Colm Tóibín’s The Testament of Mary is a brilliantly constructed, devastating account of a mother’s experience of the execution of her son, and of her life afterward. Tóibín’s secularization and demystification of a religious story becomes the internal monolog of Mary, witness to one of the most pivotal stories in the history of humanity. Her testament is the heretical récit of a human being mourning the loss of a loved one. –Rawi Hage, author of Beirut Hellfire Society

Claire-Louise Bennett, Checkout 19

(Riverhead Books)

Claire-Louise Bennett’s Checkout 19 felt like that Christmas present you long for as a child, the one you have a feeling will magically connect you to the future, and that you therefore very seldom, if ever, get. Just to be clear, I loved Pond and was waiting impatiently for her second book, but when it arrived, I was not expecting it to blow me away the way that it did, by making writing and reading, menstruation, imagination, class, identity, and thought the centre of a novel where the strings of thought, and the evaporation of a dramaturgical outline—which instead presents itself through thematic patterns and wild, enlarging digressions—transforms such elements as “voice,” “narrator,” “story.” It is rebellious, intelligent, brilliant. The second great love I have not finished reading and will continue reading and loving well into 2022 is Dorthe Nors’ North Sea.

This is a collection of essays about life at the coastline of Denmark. A strong, personal, and moving portrait of a landscape and of a mind—about loneliness, memory and belonging, in wind and waves, time, place—it is hypnotic, consoling. Thirdly I’d like to say that I loved Tarjei Vesaas’ short story “Japp”, about a dog who lies petrified on a cliff, after his “great friend and master” has slipped and fallen off the very same cliff and now lies dead on the ground far below. Have I ever read a short story about a petrified dog on a cliff before, and felt shattered to the very core of my being? No. –Gunnhild Øyehaug, author of Present Tense Machine, translated from the Norwegian by Kari Dickson, forthcoming in 2022 from Farrar, Straus & Giroux

Percival Everett, The Trees

(Graywolf Press)

I read Percival Everett’s new novel The Trees a couple of months ago and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about the book since. A murder mystery set in Money, Mississippi turns out to be a portal to supernatural vengeance; various conspiracies; and, above all, histories that will not stay buried. The Trees is grisly, surreal, bitingly hilarious. I could keep going, but honestly none of these descriptors can do justice to the experience of reading The Trees. I don’t think I’ve ever read a novel like this one before and don’t expect I will again any time soon. –Laura van den Berg, author of I Hold a Wolf by the Ears: Stories

César Aira, How I Became A Nun

(New Directions)

For the first time in a long while, I went back to closely read César Aira’s How I Became A Nun. Words break up our world into segments, and they’re inevitably caught up in metaphor. But Aira, while using language, displays in every sentence the essence of what could only be called the true, pre-metaphorical form of the world. There’s nothing strange to what Aira writes, but if I were to find something strange in it, it would have to be the way that I experience the things he’s written: as if they were my own memories, how deeply familiar they feel to me. When I read Aira’s work, I find my mind completely at peace. In Japan, The Literary Conference and How I Became A Nun have appeared in translation. –Mieko Kawakami, author of Breasts & Eggs, Heaven, and All the Lovers in the Night, forthcoming in May of 2022 with Europa and Picador, all translated from the Japanese by Sam Bett and David Boyd, who translated this citation too.

Etel Adnan, Sea & Fog

(Nightboat Books)

At the start of 2021, on and off, I flitted in and out of Etel Adnan’s magnificent body of work, some ten books of poetry. Fragments stayed in my head, throttling like an engine left on in absolute darkness. When news came of her passing this autumn, I returned to her work, staying with, and reading slowly, Sea and Fog, her collection of prose poems. She says in one of the sea sentences early in the book: “Water’s iridescence is language,” and such indeed is Adnan’s language. Later in the fog sentences, she writes: “To close one’s eyes is to create one thousand fogs.” Reverie is ecstasy, and Adnan’s Sea and Fog is a work of passionate wisdom. I now consider it my Book of Common Prayer. –Ishion Hutchinson is the author of two collections of poetry and the collection of essays, Fugitive Tilts, forthcoming in 2022

Halldór Laxness, Independent People

(Vintage)

Urged to read an epic novel about Icelandic sheep-farmers in the early twentieth century I was less than enthusiastic. How foolish of me! Independent People by Halldór Laxness was one of the great immersive imaginative reads of my life. I read it with my eyes popping out on stalks, as if I were fifteen again, gasping with shock, chortling at the pervasive flinty humor, moved to tears by the staunchness of his characters and their fate. –Helen Simpson, author of Cockfosters: Stories

Jamaica Kincaid, My Garden (Book)

(Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Jamaica Kincaid is an author whose voice, technique and perspective I admire so much that I’d read anything she writes. In fact, I believed I had read everything she’s published. But this summer a neighbor who has been helping me tend my garden in the Bronx recommended Kincaid’s collected essays on gardening: My Garden (Book), which I had never read. I think I avoided this book twenty years ago when I was deep in my phase of devouring Kincaid’s writing, because it seemed so decidedly middle-aged a subject. What did I care in my twenties about gardening? Now I am decidedly middle aged, and in possession of a garden; the same age as Kincaid when she wrote the best of these essays—such as “The Old Suitcase”—which are of course about more than gardening, and offer wisdom about leisure, art, sustenance, colonization, language, and regeneration. –Emily Raboteau, author of Searching for Zion: The Quest for Home in the African Diaspora

Anthony Trollope, The Way We Live Now

(Modern Library)

The last time I was in this round-up I was talking about Larry McMurtry and the Lonesome Dove series. Anyway, I recommended it to my sister, an English prof who writes about the 19th-century. She ran through them like Reese’s Pieces (they’re pretty long books) and said they reminded her of Trollope—her counter-suggestion was The Way We Live Now, a domestic epic about literary and aristocratic London, set in the 1870s. So I started reading. My first impressions weren’t great. Characters seemed lightly sketched, along more or less stereotypical lines—the morally bankrupt financier (headed for the other kind later on), the feckless son, the untrustworthy American, the conniving writer . . . The settings were soap-operaish, grand houses, big parties, the action melodramatic, sudden arrivals and reversals of fortune . . . the whole thing seemed written at great speed . . . yet as I kept turning the pages, something seemed to accumulate, the sketches started filling in, the characters took on substance and weight. Trollope was happy to change his mind about them, so I did, too, and the sequence of events felt less inevitable and more and more like life. Or even if not like life (at least, not the life I live in London in the 2020s), then at least intricate enough on its own terms the difference didn’t seem to matter. By the end I liked it much more than many better books. –Benjamin Markovits is the author of eleven novels, including You Don’t Have To Live Like This, Christmas in Austin, and The Sidekick, forthcoming from Faber & Faber in June 2022.

Violette Leduc, La Bâtarde

(Dalkey Archive Press)

I was feeling blue one afternoon, so I sought out a very particular cure for feeling sorry for one’s self: Violette Leduc. I reread her masterpiece La Bâtarde. Leduc turns being unloved and broke and unglamorous, into wondrous outrage. If you are feeling restless, reading Leduc mourn the size of her nose for several chapters, will make you feel there is a luxury to sadness and such words for it too! –Heather O’Neill is an author whose works include Lullabies for Little Criminals and The Lonely Hearts Hotel. Her novel When We Lost Our Heads is forthcoming in February 2022 from Riverhead.

Henry James Collected Stories

(Everyman’s Library)

In 2021, I went back to reading short stories. I very much enjoyed re-reading Henry James’s Collected Stories. I loved them in my early twenties, and they felt like a homecoming—which is ironic because home is precisely what I’ve been fed up with most of the year (and why I should feel especially at home in James’s ghost stories is another question altogether). –Jakuta Alikavazovic, author of Night As It Falls, translated from the French by Jeffrey Zuckerman

László Krasznahorkai, The Last Wolf

(New Directions)

I loved László Krasznahorkai’s short story The Last Wolf, which was published as a stand-alone book in France, where I live and write. What do we lose when we lose a species? he asks—for me, 2021 was all about feeling haunted. –Jakuta Alikavazovic, author of Night As It Falls, translated from the French by Jeffrey Zuckerman

Camila Sosa Villada, Las Malas

Las Malas / Les Mauvaises by Camila Sosa Villada is the most important book I’ve read on sexuality since Jean Genet. Sosa Villada tells the story of a gay child who one day become a flamboyant woman, living in a community of prostitutes. It’s about friendship, desire, violence. It defies all the current frames of politics and literature, it’s a fragment of future. –Édouard Louis, author of The End of Eddy, translated by Michael Lucey, and A Woman’s Battles and Transformations: A Novel, translated by Tash Aw, forthcoming in 2022.

Diana Vreeland, Allure

(Chronicle Books)

This year, my most delightful read was Diana Vreeland’s Allure. This is the third time I have pulled out the oversized red hardback to get reacquainted with the old girl. During her illustrious career in fashion (26 years at Harper’s Bazaar and 8 years as Editor-In-Chief at Vogue), Vreeland met EVERYONE. She somehow managed to meet or know every glamorous actor, singer, model, society person, tycoon, major and minor royal, and artist of note. Sometimes I suspect she was exaggerating or just lying, which is weird because her actual life was so fabulous without any embellishments. Honestly, I don’t care if she lies sometimes, because it is all so fun and charming. She is such a keen observer of people and such an avatar of excess. She connects dots in such a Diana way, as when she said that Brigitte Bardot was a creature of the 50s who made way for the 60s. “Her lips made Mick Jagger’s lips possible!” God, I love that.

Vreeland’s writing voice is so very, I don’t know, draggy. So excessive, so florid. Her prose seems to shed marabou feathers and sequins with every paragraph. She was a relentless name dropper (Mick Jagger, Jackie O, Marilyn Monroe, Maria Callas, Rudolf Nureyev, Josephine Baker, and etcetera), but she is not what I would call a snob. I think she liked anyone who was interesting, regardless of their standing in life. She was riveted by allure above all else. In Allure, she explores that ineffable, utterly unteachable ability that certain people have to draw and hold your attention and affections. During this dark and challenging year, it was such a pleasure to submerge myself in a world where the littlest, most frivolous, most froufrou things become the very most important things. EVER. –Jaime Cortez, author of Gordo: Stories

Paul Auster, The Burning Boy

(Henry Holt & Company)

I’d had galleys of Paul Auster’s thrilling biography of Stephen Crane, The Burning Boy, for two months before I read it, but once I began, I couldn’t stop. It’s a book about America at a time in the 19th century I didn’t know—after the Civil War but before Modernism (Crane’s dates were 1871-1900)—and a writer I was pretty much ignorant of, except for the odd brilliant poem and The Red Badge of Courage which I read in high school. Auster’s book resembles the kind of long, immersive novel Crane never wrote. Embraced by an old novelist’s exacting sympathy, one loses oneself in his subject, a prodigy who never grew old, who suffered terribly from poverty in a gritty boisterous and cruel USA, and who produced a bold and extensive body of work which Auster seamlessly and extensively quotes, evaluates and folds into the life. A treat are portraits of Crane’s vividly documented friendships with Joseph Conrad, Henry James who wept when he died, and HG Wells, all of whom frequented the house Crane and his common law wife Cora maintained in the south of England the last two years of his life. –Honor Moore is author of Our Revolution: A Mother and Daughter at Midcentury and, co-editor for the Library of America, of Women’s Liberation! Feminist Writings that Inspired a Revolution and Still Can.

Edward P. Jones The Known World

(Amistad Press)

I first read Edward P. Jones’ stories in Lost in the City, his debut collection, and then, loving the modest brilliance of his prose and yearning for the pull of a novel I dove into his 2003 Pulitzer Prize winner The Known World. How it is characterized, as the story of a Black slaveholder in Virginia before the Civil War, does not begin to describe what the book actually is, which is an immersive, utterly moving, shock of a fully peopled world which seems to rise like some lost testament from the page. I am within his characters as they move through their lives and become known to me. He’s a kind of James Baldwin inflected Thomas Hardy, with the former’s insistence on history and the latter’s sense of landscape, fragility and human wildness. –Honor Moore is author of Our Revolution: A Mother and Daughter at Midcentury and, co-editor for the Library of America, of Women’s Liberation! Feminist Writings that Inspired a Revolution and Still Can.

Nadifa Mohamed, The Fortune Men

(Knopf)

Nadifa Mohamed’s The Fortune Men reads as if the author could not prevent herself from inhabiting this true-life story of a miscarriage of justice. As if she were propelled to the 1950s by a powerful sense of injustice and all she needed to do was guide us around a territory that will be achingly familiar for some readers, and hideously new for many others. A young black man is convicted for a murder he did not commit. We are made privy to details of space, sounds, visuals and mood. A masterful blend of the universal and specific. Not any black man, not any murdered spinster but distinctive characters palpitating on the page. A chronicle of the African diaspora, specifically the East African, Somali experience. The British, specifically Welsh working-class experience. Black British history. British Muslim history, the immigrant sense of community. The novel is conscientious in depicting the day-to-day struggles of being constantly in debt, constantly in poor housing conditions. The cultural vertigo of the outsider, his struggle with the language, eating with his hands and knowing the disdain this triggers, trying to guess and double-guess how white people think—police, judge, jury and the prison wardens who will sling the noose around his neck. –Leila Aboulela, author of Bird Summons

francine j. harris, Here is the Sweet Hand

(Farrar, Straus, Giroux)

Since the lockdown in 2020, a book that I keep rereading and rereading is francine j. harris’ Here is the Sweet Hand, which received a well-deserved 2020 National Book Critics Circle Award in Poetry. What harris manages to do in her poetry is miraculous. harris is unafraid to take in, and take on, everything. Each poem creates a kind of journey of language, to get to what is felt, trying to stay ahead of itself, truly avant garde, a profoundly introspective language that is always moving toward a hoped-for sense of justice and an envisioned beauty. harris’ poems are sonically and visually dazzling in their emotionally intricate vocal combinations of the political, intellectual and erotic, playfully pushing the boundaries of grammar and syntax into ever-new aesthetic spaces. A moral intensity also infuses harris’ poetry, a source of which is found in harris’ Detroit, the city of her birth, a city she loves: a passionate, tough-minded, spiritually-centered Detroit attitude informs all of harris’ work. harris’ poems will transport you and they will transform you, like all great poetry does. –Lawrence Joseph, author of A Certain Clarity: Selected Poems

Alexandra Richie, Faust’s Metropolis

(Hogarth Books)

I greatly admired Faust’s Metropolis, Alexandra Richie’s brilliant history of Berlin. It’s a long book that moves swiftly thanks to the liveliness of Richie’s prose and the inherent drama of her narrative. But what makes it well worth reading, even if you have limited interest in Berlin, are Richie’s meditations on the warping of historical memory. Time and again, she demonstrates how a succession of German governments have sanitized and simplified the past to legitimize their political aims. This book ultimately tells two parallel narratives: a history of Berlin and a chronicle of how Berliners have understood their history. It’s outstanding. –Anthony Marra, author of Mercury Pictures Presents, forthcoming from Hogarth Books in July 2022

Anthony Doerr, Cloud Cuckoo

(Scribner Book Company)

I recently read Anthony Doerr’s Cloud Cuckoo Land and it stayed with me, especially the parts about the 1453 siege of Constantinople. Following several storylines and through various time zones it is a marvelous novel that can only be savored, not rushed. It’s a book about this mysterious love that continues to connect us all: the love of written manuscripts. –Elif Shafak, author of The Island of Missing Trees

Cal Flyn, Islands of Abandonment

(Viking)

In Islands of Abandonment, Cal Flyn visits places from which humans have departed: an island off the coast of Scotland, parts of Detroit; Verdun, the burial site of First World War chemical weapons. Her descriptions of the ability of plants and animals to survive man’s ecological vandalism contain hope. The outlook for humans feels less so. –Aminatta Forna, author of The Window Seat: Notes from a Life in Motion

Federico Garcia Lorca, Selected Poems

(Oxford University Press)

Life became smaller still and my reading patterns changed, again. Even more reading, even more scattered. Books sit where people might have sat with wine and laughter. I bought Federico Garcia Lorca’s selected poems and read them for the first time. The Oxford World’s Classics edition I have, offers the poems side by side in Spanish and English, which does something to me I am still trying to understand. I have returned to them frequently over the last few months. There’s some very large living on those pages. –Michael Salu is a writer, artist and creative director.

Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse-Five

(Modern Library)

Another deeply weird year. Perhaps this is normality now. The weird is normal and if we ever encountered the normal again we would find it deeply weird. So it goes, as Vonnegut writes a thousand times in Slaughterhouse-Five. I re-read that earlier this year—still very funny and very sad. –Joanna Kavenna, author of Zed: A Novel

Wolfram Eilenberger, Time of the Magicians

(Penguin Books)

I read a lot of books about people trying to carry on in the face of prevailing carnage and among these my favorite was Time of the Magicians by Wolfram Eilenberger, which is brilliant if very sad too. –Joanna Kavenna, author of Zed: A Novel

Werner Herzong, Of Walking in Ice

Werner Herzong, Of Walking in Ice

(University of Minnesota Press)

I loved Of Walking in Ice by Werner Herzog, in which he walks from Munich to Paris so Lotte Eisner doesn’t die. He is convinced this unorthodox tactic will cure her and perhaps it does, as when he arrives Eisner is fine, but Herzog thinks he is dying. It turns out he just has really bad blisters. It’s a great post-Hamsun book. –Joanna Kavenna, author of Zed: A Novel

Wislawa Szymborska, How to Start Writing (and When to Stop)

(New Directions)

Another tragic-comic classic I enjoyed this year is How to Start Writing (and when to Stop) by Wislawa Szymborska, her advice to authors. Sensibly enough her main advice is Stop writing! And never start again!—but no one believes her. Me neither. So it goes (one more time)… –Joanna Kavenna, author of Zed: A Novel

Isabel Waidner, Sterling Karat Gold

(Peninsula Press)

Isabel Waidner’s Sterling Karat Gold (out in the US in 2022) is a madly brilliant and deeply sane novel that reveals surrealism as possibly the most effective way of talking about the political moment we find ourselves in. It has time travel (constrained by Google Maps), fashion, friendship and matadors. What’s not to love? –Kamila Shamsie, author of Home Fire

Tahmima Anam’s The Startup Wife

(Scribner Book Company)

Tahmima Anam’s The Startup Wife is one of the sharpest novels I’ve read on the power dynamics between women and the men they love. It’s fresh and funny and so astute about a changing world and the things that aren’t changing in it. –Kamila Shamsie, author of Home Fire

Teju Cole, Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time

(University of Chicago Press)

The best book I read this year is Teju Cole’s Black Paper: Writing in a Dark Time. This collection of essays is a powerful testimony of our age, written with astonishing erudition, and at the same time very personal. For me as a reader, a special treasure in the book are the lyrical vignettes that seem to have been written by a poet. A valuable book because of its microscopic precision in detecting problems in the world, in a time of universal superficiality. –Semezdin Mehmedinović, author of My Heart: A Novel, translated by Celia Hawkesworth

Rabee Jaber, Berytus Underground City

(Gallimard)

It’s been a year of deep grief in Lebanon; as the economy has collapsed out from under us, we’ve all watched the lives we’ve built over the last two decades come swiftly and totally undone. And so it’s not surprising that the two books that have resonated most with me have been, in their own way, about grief. Though I didn’t read them in this order, first up is Lebanese novelist Rabee Jaber’s Berytus Underground City (2005)—available in French translation but not as of yet in English. A security guard in downtown Beirut chases a figure through a ruined cinema and falls into a hole. He wakes up in a stone bed deep underground, being nursed by the inhabitants of an underground city called Beirut, while the world above is known to them only as “up there.” Exploring the labyrinth below, Jaber maps all the memory holes and dark caverns beneath the unresolved grief of the civil war so expertly that, reading it in the wake of the collapse, it felt less like a piece of speculative fiction than a proof of foreknowledge. –Lina Mounzer is a Lebanese writer and translator. She writes a monthly column for the Lebanese daily L’Orient Today, chronicling social changes in the wake of the country’s economic collapse.

Hisham Matar, A Month in Siena

(Random House)

Hisham Matar’s brief essay-memoir A Month in Siena (2019) follows Matar who, long bewitched by the Sienese school of painters, takes a month-long trip to the city in the aftermath of finishing a memoir about his father (The Return, 2016), a Libyan dissident disappeared in 1990 by Qaddafi’s agents. The trip’s purpose is to spend time looking at the paintings in the museum there, but transforms into an opportunity to come to terms with the fact that he will never know what has become of his father and to finally lay his memory to rest. In the book, Matar pulls off the most delicate trick of all: writing about the redemptive power of love, art, and faith in a way that is not cloying or pat or simplistic in the least. In precise, beautiful language, he takes the reader on a real journey, recreating both the profound melancholy of loss and the quiet exaltations he has stacked against it, so that by the end of the book that arrival at a sense of redemption feels like a real choice, one earned and made not just despite, but through the experience of grief itself. –Lina Mounzer is a Lebanese writer and translator. She writes a monthly column for the Lebanese daily L’Orient Today, chronicling social changes in the wake of the country’s economic collapse.

Fanny Howe, The Winter Sun

(Graywolf Press)

Fanny Howe is a rarity in American letters: a genius who wants no laurels (I met her in 2014 when she was a finalist for the National Book Award, and after I wished her luck, she said “No: Lose! Lose!”), and a mystic who’d likely scoff at the word. These traits make me trust her, and are why I reached for her linked essays, The Winter Sun, last February, the first book I read after a concussion made reading impossible for two months. It felt momentous, which book to strive to read, which author I wanted in my book-empty brain, and I thank her for being there on my shelf, for all the “soul-forging events” she lived through to come to such singular insights, insights I’d say shine if her humility would only allow it. –Katie Ford, author of If You Have to Go

Geoffrey Brock, (ed. and tr.) The FSG Book of 20th-Century Italian Poetry

(Farrar, Straus, Giroux)

There were thankfully several books that served over the year like some gift from a god, magical shields to fend off the bald faced lies and bad juju incoming, defensive armor one could still find hope behind. There were several anthologies among them—one a reread edited by the brilliant translator Geoffrey Brock, The FSG Book of 20th-Century Italian Poetry. Reading is also an immersion into a living history. My pick is a book of poems from early in ’21: Reg Gibbons’ Renditions. Gibbons is a gifted translator, as well as a poet. I especially love his lucid Greek translations such as Sophocles Selected Poems, Odes and Fragments. A book I first read in college that I have carried with me ever since is Robert Lowell’s Imitations. It’s title is key to how it is to be read. The same can be said about Gibbon’s title, Renditions. The book is located at a radiant crossroads where literary experience and personal experience are forged into an empathetic, consoling vision. –Stuart Dybek, author of The Start of Something: The Selected Stories of Stuart Dybek

Agota Kristof, La analfabeta (Alpha Decay), Da igual (Alpha Decay), and Claus y Lucas (Libros del Asteroide)

This year I have loved discovering the Hungarian writer Agota Kristof, a kind of Marguerite Duras with the dark, raw, tender heart of MittelEuropa (La analfabeta, autobiography; Da igual; Claus y Lucas). –Pola Oloxiorac, author of Mona: A Novel, translated from the Spanish by Adam Morris

Mary Gaitskill, This is Pleasure

(Pantheon)

This is Pleasure by Mary Gaitskill is slim and edged like an arrow directed to the medulla of contemporary life. –Pola Oloxiorac, author of Mona: A Novel, translated from the Spanish by Adam Morris

Milena Busquets, Todo esto pasará, Gema, and Hombres elegantes

(Pontas)

I read everything available by Milena Busquets (Todo esto pasará, Gema, Hombres elegantes) and I can’t wait to read more from her. –Pola Oloxiorac, author of Mona: A Novel, translated from the Spanish by Adam Morris

Luke Brown, My Big Life

(Canongate)

My favorite Argentine read was My Biggest Lie by Luke Brown, an Englishman who brought me back to Buenos Aires in a comedy of awfully smart literary drifters. –Pola Oloxiorac, author of Mona: A Novel, translated from the Spanish by Adam Morris

Andrea Abi-Karam and Kay Gabriel (eds.), We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics

(Nightboat Books)

One of my constant poetic companions through this difficult year was the remarkable anthology, We Want It All: An Anthology of Radical Trans Poetics, edited by Andrea Abi-Karam & Kay Gabriel. Almost 450 pages of fascinating, challenging, beautiful and moving work from names I knew, names I should have known better and names who were new to me. It should be an immediate addition to the shelves of every poet, every school and every university. A shoutout also to Pilot Press, and Joshua Jones’ magnificent Diametric Fist Tender. Poetry which has stayed with me. –Andrew McMillan, author of physical, playtime and pandemonium, all with Jonathan Cape

Albert Samaha, Concpetion: An Immigrant Family’s Fortunes

(Riverhead Books)

Of all the books I read in 2021, I especially loved Albert Samaha’s Concepcion: An Immigrant Family’s Fortunes, and also the photography book (by Jesse Freidlin, Robert Garofalo and Zach Stafford) When Dogs Heal: Powerful Stories of People Living with HIV and the Dogs that Saved Them; the former for its gorgeous macro and micro lens on family, diaspora and empire; the latter for its celebration of survival and love—particularly in queer, trans, BIPOC lives—with the help of our canine better halves. –Elaine Castillo, author of America is Not the Heart and How To Read Now: Essays, forthcoming in 2022 from Viking and Atlantic Books

Michelle Latiolas, She

Among the most memorable books I read this year was She by my colleague Michelle Latiolais. A refusenik of a book, formally—neither stories nor a novel and not at all bothering to announce its place within the standard modes of contemporary fiction—She loosely follows an unnamed teenage runaway from Needles, Calif. across the night she arrives to start a life of her own in Los Angeles: “She’d been home-schooled for ten years, and whipped for eleven, and tomorrow she would celebrate her fifteenth birthday.” Each vignette is a stunner, precise yet organic, capable of tremendous depths and nimble enough to surprise. I loved it. –Claire Vaye Watkins, author of I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness.

Miguel Murphy, Shoreditch

(Barrow Street Press)

In Shoreditch, Miguel Murphy imagines his medical regimen as a video game, taking out alien mutations. In another poem he feels the ripples of implication as Greg Louganis hits the Olympic diving pool. Injuring his head, bleeding his hiv infected blood into the water. Theatrical, historical, personal, this book ties together plagues old and new, along with the violence experienced by queer men over centuries of abuse and, ultimately, their strength and survival. It’s an inspiring read, full of filth and longing. –D.A. Powell, author of Atlas T

Bryan Washington, Memorial

(Riverhead Books)

Bryan Washington’s Memorial is a brilliant novel: artfully constructed and somehow both hard-hitting and tender, it’s a book that knows a great deal about what makes people tick. I read it back in January and still think of Mike and Benson with fondness today. –Sunjeev Sahota, author of China Room: A Novel

John Steinbeck, The Log from The Sea of Cortez

(Penguin Group)

A work I had been meaning to read for ages, John Steinbeck’s The Log from The Sea of Cortez is the narrative of the 1941 book by Steinbeck and boho marine biologist Ed Ricketts, minus the catalog of the creatures found by the two and their crew on a specimen-collecting expedition to the waters of Mexico. What’s interesting about having read it this year is that Steinbeck embarks on this journey of several weeks knowing the world is on fire. That time spent in the Gulf of California—working on the boat, picking through the shores—out of time and immersed in something greater than himself, reduced to just being, stuck with me. Our minds and spirits need refuge, and refuge of a sort is a lot closer than we think: in the briny tidepools, in the hold of a small ship. z–Oscar Villalon, managing editor of Zyzzyva

Matt Rohrer, The Sky Contains the Plans

(Wave Books)

The books I began and am ending 2021 with have bracketed this strange year in memorable ways. I spent a few January pandemic days with Matt Rohrer’s The Sky Contains the Plans, reading in the below-freezing air outside my favorite NYC cafe, which was only open for take-out. Wearing my heated vest, heated socks, and sitting on a heated stadium seat with my cafe con lèche, I laughed aloud at Rohrer’s fabulously inventive poems, each of which begins with a line that came to him at the edge of sleep (hypnagogic, he calls it) and unfolded its tender luminous shocks to deliver jolts of pleasure to my anxious mind. z–Catherine Barnett, author of Human Hours: Poems

G. Gabrielle Starr, Feeling Beauty: The Neuroscience of Aesthetic Experience

(MIT Press)

And then this fall I found G. Gabrielle Starr’s eye-opening Feeling Beauty: The Neuroscience of Aesthetic Experience and Starr’s description of the default mode network, which can “link aesthetic experience to…a heightened sense of both the external world and its internal, subjective representation” and which is just what Rohrer’s poems were doing to me. This network goes offline when you’ve got tasks to accomplish but lights up in response to art and, when lit, leads to other essential longed-for states of being: mind-wandering, understanding others. z–Catherine Barnett, author of Human Hours: Poems

Clarice Lispector, The Hour of the Star

(New Directions)

Dripping with stunning prose, The Hour of the Star, by Clarice Lispector, has the depth of an ocean. For the Brazilian novelist Clarice Lispector to capture so much beauty, truths about life and death, and the process of telling the story in a few words while transcending genre boundaries is a testament to her immense skill. This book epitomizes the greatness of short novels. –Sulaiman Addonia, author of Silence is My Mother Tongue

Tom Lutz, The Kindness of Strangers

(University of Iowa Press)

I loved The Kindness of Strangers by Tom Lutz. Each step Tom takes in this compendium of world journeys is an enlightenment. I am mesmerized at how the word of the peoples is cradled in this tour de force. –Juan Felipe Herrera, author of many books, including, most recently, Imagina.

Justin Torres, We The Animals

(Mariner Books)

I don’t know if I was living in a hole back in 2012, but I somehow missed the release of Justin Torres’ We The Animals, and all its attendant (and deserved) adulation. When I picked up the book earlier this year, I was floored—at the kinetic dynamism between the book’s brothers, at how Torres’ prose manages to be liquid-lyric and laser-sharp all at once. I can’t believe I lived without this book for so long. –Lauren Markham, author of The Far Away Brothers

Pierrine Poge, Warda s’en va, Carnets du Caire

(La Baconniere)

I read Pierrine Poget, Warda s’en va, Carnets du Caire, in which a young swiss French speaking woman (she usually writes poetry) is alone in Cairo and trying to keep a diary there, then re-reading it and commenting on it. It’s a delicate, subtle book about time passing and perceptions, about walking as a woman alone, and about the simple pleasure of being abroad in another culture and meeting new people. A too discreet book. I loved it. –Marie Darrieussecq, author of Being Here Is Everything: The Life of Paula Modersohn-Becker, translated from the French by Penny Hueston

Maceo Montoya, Preparatory Notes for Future Masterpieces

(University of Nevada Press)

One of my 2021 faves was Preparatory Notes for Future Masterpieces by Maceo Montoya. Channeling the spirit of Candide, Montoya’s use of humor, pathos, and satire to tell the story of a misunderstood artist clamoring for his place in posterity and his voice to be heard, had me laughing from beginning to end. –Reyna Grande, author of The Distance Between Us: A Memoir, and A Ballad of Love and Glory: A Novel

Pola Oloixarac, trans. by Adam Morris, Mona

(Farrar, Straus, and Giroux)

One of the most unforgettable books I read this year was Pola Oloixarac’s brilliant, provocative and fearless Mona (translated from the Spanish by Adam Morris.). Mona is a force, and the novel’s irreverent, unfiltered, and often hilarious send-up of the rarefied world of academia and literary culture is exhilarating. The pages blaze—I read it in a single day, and it stays with me. I also kept returning to Alex Dimitrov’s Love and Other Poems. Dimitrov’s obsessive subjects—love and desire and the passage of time—find full expression in poems that feel both of-the-moment and timeless. The poems move with the power of music–they are music–and, while often saturated with pain, are also lush with the abundant pleasures of inhabiting a living body. –Deborah Landau, author of Soft Targets and Skeletons: Poems, forthcoming in 2023

Michael Chabon, Moonglow

(Harper Perennial)

Michael Chabon’s Moonglow helped me to clear the haze of the pandemic. Written in an intuitively nonlinear style that mimics how we piece together family history, this fictionalized biography, narrated by an author proxy named “Mike” Chabon, recounts the life and times of Mike’s grandfather, devoting lots of space to a woefully overlooked topic: late-life romance. One night in the “luminous Florida dark” of the Fontana Village retirement community, Mike’s grandfather hears his neighbor Sally Sichel yelling for her cat Ramon, convinced it has been eaten by a boa constrictor. What begins as a screwball act of chivalry using improvised tools like a “snake hammer” evolves into a genuinely hot love affair, defying their emotional scars and the specter of bone cancer. Sex like this is something we want to believe can happen in our seventies but few authors are willing or able to explore, and only rarely in language so brave, comical and lush. –Sam Bett is a writer and Japanese translator, most recently of My Annihilation, by Fuminori Nakamura.

![]()

Natalia Ginzburg, Family Lexicon

(New York Review of Books)

The read of the year was a reread for me, Natalia Ginzburg’s Family Lexicon. I was walking the streets of Florence in September and walked inside a little bookshop and picked up a new edition of Family Lexicon. I had read the book in high school, quite a few years ago, vaguely unaware of the real power of language. Unaware that language shapes families, communities, cultures, entire ecosystems, that it is as much a tool of survival as it is a tool of domination and oppression, that it can bruise as much as it can cure, that it can hate as much as it can love, that sometimes it can kill. Ginzburg manages to encapsulate an enormous amount of what words can do and undo in this marvelous classic keeping everything grounded and palpable. Her account of her everyday family life from the 20s all throughout the 50s might be one of the truest and realest novels ever written. In fact, it might be o novel only because that is the lexicon that Ginzburg chose for molding it. A phenomenal radiography of a speech famine during fascism and of the vitality and resilience of language alike. –Elena Marcu is cofounder of Black Button Books, publishers of Freeman’s in Romanian.

Marguerite Yourcenar, Memoirs of Hadrian

(Farrar, Straus, and Giroux)

This year, I accepted my life as a party boy and recovered from sksksks in bed with my boyfriend and two novels that matched the highs and lows of the night life: Memoirs of Hadrian by Marguerite Yourcenar and The Transit of Venus by Shirley Hazzard. An emperor’s musings on the rise and fall of civilization combined with the brutal loss of his gay lover and the speeding diverging lives of two sisters across time and space. Books for after the afters, returning to life. –Kyle Dillon Hertz, author of The Lookback Window, forthcoming in 2023 from Simon & Schuster

Shrilal Shukla, Is Umr Men

(Prabhat Prakashan)

This past year was challenging. I felt distracted and often unmoved by words. The day to day of life seemed to eclipse what words could offer by way of insight or solace. But then I read the Hindi writer Shrilal Shukla’s Is Umr Men, or, loosely, At My Age, published in 2004. Having just translated a book of his satire, I wasn’t expecting to be as interested in his short stories. But I found myself captivated by his middle-class portraits of late 20th-century North Indian life. Reading his stories, I felt like he was speaking obliquely about the USA in 2021. In one story, a state’s governor, called in the Indian political system a Chief Minister, inspects by helicopter the devastation of a flood in the countryside. He witnesses a family hanging on for their lives in a tree, and one of his advisors remarks dryly that that is what “they” do when there are floods. The poor people of the countryside are only bestial, anthropological subjects. Or, in another story, a grandfather tries to get his grandson to speak more politely to one of the family’s servants, but the obvious incongruity between lineal servanthood and middle-class decorum makes the lesson absurd to the boy. I read the stories as reflections on the internal contradictions of middle-class life in a society where various ruptures or disconnects separate people more than connect them. There’s a lingering sense of regret and sadness about this in Shukla’s stories. And that’s my overwhelming feeling about the US today, as well. –Matt Reeck’s latest translations include Selected Satire: Fifty Years of Ignorance (Penguin-Random House India) from the Hindi of Shrilal Shukla and the forthcoming Manifestos with Betsy Wing from the French of Édouard Glissant and Patrick Chamoiseau.

Maria Ospina, trans. by Heather Cleary, Variations on the Body

(Coffee House Press)

I was very struck by Variations on the Body by Maria Ospina, translated by Heather Cleary, an incredibly thoughtful set of reflections on how violence is refracted into scenes of everyday life. Policarpa, one short story that sets the battlefield memories of a guerilla fighter within the mundane aisles of a super store, perfectly collapses categories of existence into one, unreconciled, political being. –Nimmi Gowrinathan, author of Radicalizing Her: Why Women Choose Violence

Tomás Q. Morín, Machete

(Knopf)

Near the end of Machete, Tomás Q. Morín’s terrific third book of poems, the poet writes, “God is nothing / if not a comedian,” which struck me as just the kind of incisive line I needed in these uncertain and almost inconsolable times. These are deeply pleasing poems for the unpredictable ways they extract wit, temper anger, and shape tenderness from the moments in our lives that challenge us to “say different.” –Manuel Muñoz, author of The Faith Healer of Olive Avenue and The Consequences, forthcoming in 2022 from Graywolf

Laksmi Pamuntjak, Kitab Kawin

(Gramedia)

A standout for me has been the as-yet-untranslated Kitab Kawin, by Laksmi Pamuntjak, out earlier this year with Gramedia. Loosely translated as The Book of Mating this collection explores all the connotations of the word. Informed by Pamuntjak’s work as a journalist, the short stories are told in diverse voices of female characters from across the archipelago—by turns fierce, hilarious, sensuous, horrific and tender. –Annie Tucker is a writer and translator from Bahasa Indonesia.

César Aira, trans. by Chris Andrews, The Divorce

(New Directions)

The Divorce by César Aira (translated from the Spanish by Chris Andrews) is a tiny novel that contains worlds within worlds, imagination and coincidence tethered by reality and increasingly wild scenes, like two characters jumping into a miniature model of a school to escape the same school that’s on fire, which is all triggered by a young man on a bike who is soaked by the pooled rain in an awning. Entangled, dark, breathtaking, magical, Aira’s prose is as singular as he and the multiverse pig-pile he has crafted. –Kerri Arsenault, author of Mill Town

R.J. Ivankovic, H.P. Lovecraft’s The Call of Cthulhu for Beginning Readers

(Chaosium)

This year I was delighted to discover H.P. Lovecraft’s The Call of Cthulhu for Beginning Readers by R.J. Ivankovic, Chaosium Publications, 2017. It is precisely in the manner of Dr. Seuss. Illustrations dead-on. Anapestic tetrameter as well. And you’re left with such a strange and airy gulf between this rendering and its model. Suggesting, dare I say it, even stranger, deeper gulfs. –David Searcy, author of The Tiny Bee that Hovers at the Center of the World

Catherine Taylor, Apart

(Ugly Duckling Presse)

I spent the second half of 2021 reading books of prose poems, or books I read as prose poems, and dividing them not into prose or poetry but rather into where the volumes’ authors seemed to place their authorial trust—whether in the world or in their own ideas and voices. Those who trusted the world created documentary collections that often relied on archives, like Holly Iglesias’ fascinating Souvenirs of a Shrunken World, about the 1904 World’s Fair in St. Louis, or Catherine Taylor’s Apart, which attempts to reckon with the legacy of South Africa’s apartheid. Those who mistrusted the world wrote absurdist or surrealist volumes, starting with Arthur Rimbaud’s Illuminations, continuing into our era with books that delighted me like Renee Gladman’s Event Factory or Ida Vitale’s Byobu (translated by Sean Manning).

But my favorites were the ones that defied even these two categories, focusing so narrowly on the observed world that real details rebelled and grew both ridiculous and—in their ridiculousness—poignant. These include Francis Ponge’s Unfinished Ode to Mud (translated by Beverley Bie Brahic), Robert Walser’s Microscripts (translated by Susan Bernofsky), and the fabulous 2020 collection Flèche, by Mary Jean Chan, which might have been the book I liked the best of all. –Jennifer Croft, author of Homesick and translator of Olga Tokarczuk’s Books of Jacob

Tor Ulven, Replacement

(Dalkey Archive Press)

The most demanding and at the same time the most satisfying book that I have read in recent months is Replacement the only novel written by the Norwegian poet Tor Ulven (1953-1995). There is no plot in this book. Or rather, the plot is life itself, which jumps between the past and the present without warning. Between the most intimate childhood memories (the pearls of a mother clinking before nursing her child) and the most distressing sensations that the proximity of death brings (having to sleep with a shotgun next to it that has not been fired in fifty years).

Replacement is assembled from the monologues of fifteen characters, each one distributed throughout a book that barely reaches 150 pages. All those voices in the end make up a single narrative voice. Ulven reminds us that we are inhabited by dozens of people, that we are not one as we falsely believe. –Andrés Felipe Solano, author of Los días de la fiebre: Corea del Sur, el país que desafió al virus

Catherine Lacey, Pew

(Farrar, Straus, and Giroux)

Unnamed and ambiguous narrators seem to be my thing this year, like the ones in Pew by Catherine Lacey and White on White by Aysegül Savas. Embodying a certain shapelessness and intangibility, these narrators are blank canvases for others characters to paint on. While the brushstrokes are more than fascinating, the most profound stories might be those that lie within the canvases themselves, invisible on the surface but deeply present beneath. In two confident and gracefully written novels, Lacey and Savas have given us the possibility to see into those psychological and philosophical truths that we, as readers and writers, are always on a quest to unveil. –An Yu, author of Ghost Music, forthcoming from Grove

Diane Williams, The Collected Stories of Diane Williams

(Soho Press)

My favorite book from this last year was The Collected Stories of Diane Williams, which I found myself returning to between all of the novels I was assigned in my MFA program. Picking up Williams after reading more standard literary fiction like Don Delillo was a bit like going from an indie rock concert to showing up at someone’s basement where there’s a woman playing an acoustic guitar with a coat hanger. At first you’re a little confused about what’s going on and you’re sort of worried she’s going to break a string, but after some time, watching her approach the act of playing that way changes your whole experience of listening in general. Williams’ stories are dark, hilarious, difficult, and enlivening. She also has the best titles of any short story writer out there, and she really knows her way around an exclamation point. –Elizabeth Ayre, writer and MFA student at NYU

Glenn Frankel, Shooting Midnight Cowboy

(Farrar, Straus, and Giroux)

These days I’m big on Shooting Midnight Cowboy: Art, Sex, Loneliness, Liberation, and the Making of a Dark Classic. A good book about making a movie dramatizes every aspect of the artistic process—coming up with an idea, changing it as you go, dealing with the inevitable accidents—better than one about an individual writer or artist or band. I read them all, and this is the best book of its kind. –David Kirby’s latest books are The Knowledge: Where Poems Come From and How to Write Them, and Help Me, Information: Poems.

Ross Gay, The Book of Delights

(Algonquin)

Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights got me through the darker days of 2021. A collection of short essays about things that delight the author, the book invites us to be more attentive to the world around us and to the small but profound joys that exist there. Another standout for me was Joe Wilkins’ timely novel Fall Back Down When I Die, which is impossible to put down, perfectly evokes hardscrabble eastern Montana, and might’ve made me cry just a little bit. –Amanda Rea is a writer in Denver.

Rivka Galchen, Everyone Knows Your Mother is a Witch

(Farrar, Straus, and Giroux)

This year I was grateful for stories that were both funny and grim as hell. My favorite of these was Everyone Knows Your Mother Is A Witch by Rivka Galchen. You could say this is a book for our times, given that it involves truth and untruth, as framed by Katharina Kepler’s harrowing quest to clear herself of witchcraft accusations in 17th century Germany. But it’s also a book full of weirdness and joy, in large part due to Katharina’s voice—brilliant, blunt, and unforgettable. –Tania James, author of The Tusk That Did the Damage

Anna Swir, trans. by Czeslaw Milosz, Talking to My Body

(Copper Canyon)