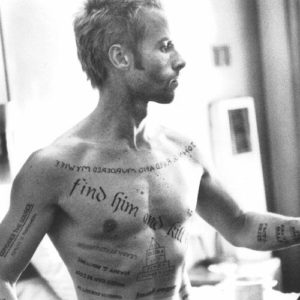

8 of the best tattoos in literature.

As I recently discovered, if you google “tattoos in literature,” the overwhelming majority of results will be photo listicles of tattoos inspired by works of literature, which is not what I asked for, Larry.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not one of those people who think getting a literary quote or silhouette of a literary character inked on your body is stupid. Quite the contrary, in fact. I, for the most part, love that shit and save my scorn for only the very lamest incarnations (do spare a thought for the millions of well-meaning Potterheads, inked to the back teeth with Hogwarts house sigils, having to watch in horror as the world’s wealthiest TERF burns down their childhood along with her own legacy). It’s just that the history of tattooing, it’s significance across various cultures and eras, and its (rare but often delightful) appearances in fiction, always seemed more interesting to me than catching sight of a So It Goes or Not All Those Who Wander Are Lost tat at a bar.

Here then are eight examples, drawn from a 150 year period, of tattoo and tattooing descriptions in literature:

from Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), in contemplation of Queequeg’s markings:

And this tattooing, had been the work of a departed prophet and seer of his island, who, by those hieroglyphic marks, had written out on his body a complete theory of the heavens and the earth, and a mystical treatise on the art of attaining truth; so that Queequeg in his own proper person was a riddle to unfold; a wondrous work in one volume; but whose mysteries not even himself could read, though his own live heart beat against them; and these mysteries were therefore destined in the end to moulder away with the living parchment whereon they were inscribed, and so be unsolved to the last.

from Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island (1882), when a mysterious sea captain arrives at the Admiral Benbow inn with ink on his arm:

‘Here’s luck,’ ‘A fair wind,’ and ‘Billy Bones his fancy,’ were very neatly and clearly executed on the forearm; and up near the shoulder there was a sketch of a gallows and a man hanging from it—done, as I thought, with great spirit.

from W. B. Yeats’ The Celtic Twilight: Faerie and Folklore (1893), as Yeats discusses faeries with the pagan Irish:

There are some doubters even in the western villages. One woman told me last Christmas that she did not believe either in hell or in ghosts. Hell she thought was merely an invention got up by the priest to keep people good; and ghosts would not be permitted, she held, to go ‘trapsin about the earth’ at their own free will; ‘but there are faeries,’ she added, ‘and little leprechauns, and water-horses, and fallen angels.’ I have met also a man with a mohawk Indian tattooed upon his arm, who held exactly similar beliefs and unbeliefs. No matter what one doubts one never doubts the faeries, for, as the man with the mohawk Indian on his arm said to me, ‘they stand to reason.’ Even the official mind does not escape this faith.

from the prologue to Ray Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man (1951), as the unnamed narrator gazes for the first time on the body of a haunted former member of a carnival freak show:

I cannot say how I sat and stared, for he was a riot of rockets and fountains and people, in such intricate detail and color that you could hear the voices murmuring small and muted, from the crowds that inhabited his body. When his flesh twitched, the tiny mouths flickered, the tiny green-and-gold eyes winked, the tiny hands gestured. There were yellow meadows and blue rivers and mountains and stars and suns and planets speed in a Milky Way across his chest. The people themselves were in twenty or more odd groups upon his arms, shoulders, back, sides, and wrists, as well as on the flat of his stomach. You found them in forests of hair, lurking among a constellation of freckles, or peering from armpit caverns, diamond eyes aglitter. Each seemed intent upon his own activity; each was a separate gallery portrait.

from J. D. Salinger’s Franny and Zooey (1961):

We’re freaks, that’s all. Those two bastards got us nice and early and made us into freaks with freakish standards, that’s all. We’re the tattooed lady, and we’re never going to have a minute’s peace, the rest of our lives, until everybody else is tattooed, too.

from tattooed poet Thom Gunn’s poem, “Blackie, the Electric Rembrandt” (1961):

We watch through the shop-front while

Blackie draws stars—an equal

concentration on his and

the youngster’s faces. The hand

is steady and accurate;

but the boy does not see it

for his eyes follow the point

that touches (quick, dark movement!)

a virginal arm beneath

his rolled sleeve: he holds his breath.

…Now that it is finished, he

hands a few bills to Blackie

and leaves with a bandage on

his arm, under which gleam ten

stars, hanging in a blue thick

cluster. Now he is starlike.

from Jonathan Nolan’s short story “Memento Mori” (2001), in which a man with anterograde amnesia tattoos notes onto his own body in an attempt to find out who killed his wife:

He can hear the buzzing through his eyelids. Insistent. He reaches out for the alarm clock, but he can’t move his arm.

Earl opens his eyes to see a large man bent double over him. The man looks up at him, annoyed, then resumes his work. Earl looks around him. Too dark for a doctor’s office.

Then the pain floods his brain, blocking out the other questions. He squirms again, trying to yank his forearm away, the one that feels like it’s burning. The arm doesn’t move, but the man shoots him another scowl. Earl adjusts himself in the chair to see over the top of the man’s head.

The noise and the pain are both coming from a gun in the man’s hand—a gun with a needle where the barrel should be. The needle is digging into the fleshy underside of Earl’s forearm, leaving a trail of puffy letters behind it.

from Sarah Hall’s The Electric Michelangelo (2004), which follows the journey of an interwar Coney Island tattoo artist and his mysterious circus performer muse:

To tattoo was to understand that people in all their confusing mystery wanted only to claim their bodies as their own site, on which to build a beacon, or raise a rafter, or nail up a manifesto, warning, celebrating, telling of themselves. It was to understand that in order for a body to be reborn and re-yoked, first it needed to be destroyed and freed. It was emancipation and it was slavery, the ashes and the phoenix. It was beauty and destruction, it was that old trick. That was the contract.

Dan Sheehan

Dan Sheehan is the author of the novel Restless Souls (Ig Publishing) and Editor-in-Chief of Book Marks.