8 Great Movies Based on Unusual Literary Source Material

Putting all those old letters and Arlo Guthrie songs to use

Today, the newest retelling of the story of the JFK assassination comes to the big screen: Pablo Larraín’s Jackie, which is based on and centered around an interview Jackie Kennedy gave to a reporter for LIFE Magazine just a week after President Kennedy was killed. An interview—even a famous one—strikes me as a somewhat unusual piece of writing to pin a film on. Usually, film adaptations are based on something a bit meatier—a novel, a memoir, or a longform work of nonfiction. But the strange source material has by all accounts made for an elegant, unique film, an “anti-biopic” of sorts, that allows high feeling and deep focus on the person at its center. To further investigate, find below a brief survey of Jackie and a few other great films based on unusual literary source materials—from diaries to letters to newspaper articles to songs.

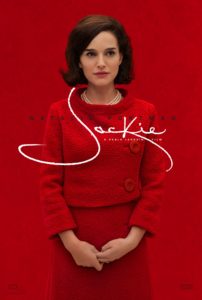

Jackie

Pablo Larraín’s newest feature is a portrait of Jackie Kennedy in the immediate aftermath of her husband’s assassination. It is based primarily on the famous “Camelot” interview that Jackie Kennedy gave to Theodore H. White in 1963, just a week after JFK’s death—a piece of prodigious fiction-making itself—and the film uses the interview itself as a loose structure. (NB: this isn’t even Larraín’s only literary anti-biopic to hit theaters this month—his Neruda comes out in two weeks.)

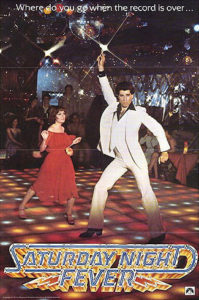

Saturday Night Fever

The movie that made John Travolta a star was actually based on “Tribal Rites of the New Saturday Night,” a 1976 article in New York Magazine by Nik Cohn, which documented the lives of young disco-goers in 1970s Brooklyn. Except that, as it turned out, those lives were completely fabricated. “My story was a fraud,” Cohn admitted years later. “I’d only recently arrived in New York. Far from being steeped in Brooklyn street life, I hardly knew the place. As for Vincent, my story’s hero, he was largely inspired by a Shepherd’s Bush mod whom I’d known in the Sixties, a one-time king of Goldhawk Road.” I’d say that means Cohn probably deserves a writing credit.

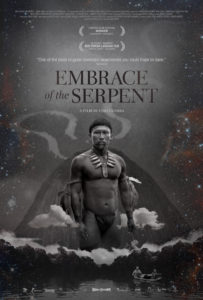

Embrace of the Serpent

Ciro Guerra’s award-winning and highly acclaimed 2015 film is based on the diaries of Theodor Koch-Grunberg and Richard Evans Schultes, scientists who studied the people, plants and strange mysticisms of the Amazon—and in Koch-Grunberg’s case, died doing it. In fact, an old photo of Koch-Grunberg, discovered by anthropologist Ignacio Prieto, a friend of Guerra, may be responsible for the film’s very existence. Good thing it wasn’t just a photograph, or the movie would have been quite a bit shorter.

A Nightmare on Elm Street

Like all the scariest horror stories, this classic fright-fest has its origins in reality—in this case, the newspaper. As director Wes Craven explains:

“It was a series of articles in the LA Times, three small articles about men from South East Asia, who were from immigrant families and who had died in the middle of nightmares—and the paper never correlated them, never said, ‘Hey, we’ve had another story like this.’ The third one was the son of a physician. He was about twenty-one; I’ve subsequently found out this is a phenomenon in Laos, Cambodia. Everybody in his family said almost exactly these lines: ‘You must sleep.’ He said, ‘No, you don’t understand; I’ve had nightmares before—this is different.’ He was given sleeping pills and told to take them and supposedly did, but he stayed up. I forget what the total days he stayed up was, but it was a phenomenal amount—something like six, seven days. Finally, he was watching television with the family, fell asleep on the couch, and everybody said, ‘Thank god.’ They literally carried him upstairs to bed; he was completely exhausted. Everybody went to bed, thinking it was all over. In the middle of the night, they heard screams and crashing. They ran into the room, and by the time they got to him he was dead. They had an autopsy performed, and there was no heart attack; he just had died for unexplained reasons. They found in his closet a Mr. Coffee maker, full of hot coffee that he had used to keep awake, and they also found all his sleeping pills that they thought he had taken; he had spit them back out and hidden them. It struck me as such an incredibly dramatic story that I was intrigued by it for a year, at least, before I finally thought I should write something about this kind of situation.”

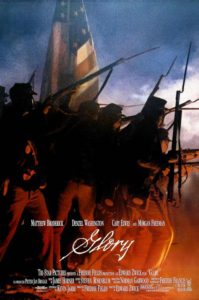

Glory

This heavily gilded 1989 film (Denzel Washington cleaned up in awards season) is partially based on the personal letters of Robert Gould Shaw, the Union Colonel portrayed by Matthew Broderick. A white soldier from abolitionist roots, Shaw is famous for taking command of the army’s first all-black regiment and encouraging them to fight for fair pay. Over the course of the Civil War, Shaw wrote over 200 letters to family and friends, which apparently contained enough stories to also power a book, Peter Burchard’s One Gallant Rush.

The Indian Runner

Sean Penn’s 1991 drama is based on Bruce Springsteen’s “Highway Patrolman.” Yes, that’s right. Well, you can’t deny that this is a good setup: “My name is Joe Roberts I work for the state / I’m a sergeant out of Perrineville barracks number 8 / I always done an honest job as honest as I could / I got a brother named Franky and Franky ain’t no good…” Are you thinking “I’d watch that movie”? Because you can. (If Bob Dylan can win the Nobel Prize in Literature, I can count Bruce Springsteen songs as literary sources.)

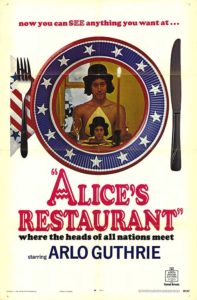

Alice’s Restaurant

This movie, based on Arlo Guthrie’s famous, rambling 1967 track “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree”—itself based on an actual event from his life—stars Guthrie as himself, is a political comedy largely forgotten today, but much discussed in its time. Director Arthur Penn even took home an Oscar nomination. (Ditto Arlo Guthrie songs.)

The End of the Tour

Technically this film is based on David Lipsky’s memoir Although of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself, but since that memoir was almost entirely based on an extended interview from Lipsky’s five-day road trip with David Foster Wallace, I’m counting it.

Emily Temple

Emily Temple is the managing editor at Lit Hub. Her first novel, The Lightness, was published by William Morrow/HarperCollins in June 2020. You can buy it here.