8 Gilded Age Stories That Predicted the Future

These Writers Foresaw Solar Power, the Internet, and Vaping

Between 1880 and 1920, America was fixated on the future. To many, it felt as though society was on the verge of breaking into a utopian, dystopian, or post-apocalyptic new world order. Modernity was closing in around them: railroads belted the country, dissolving the frontier. Gender roles were being renegotiated as more women sought education and work outside the home. The Great Migration from rural Southern states to the great cities began, and racialized tensions reached a post-slavery crisis point. Thinkers and readers turned to fiction to explore questions and anxieties about what the future might hold.

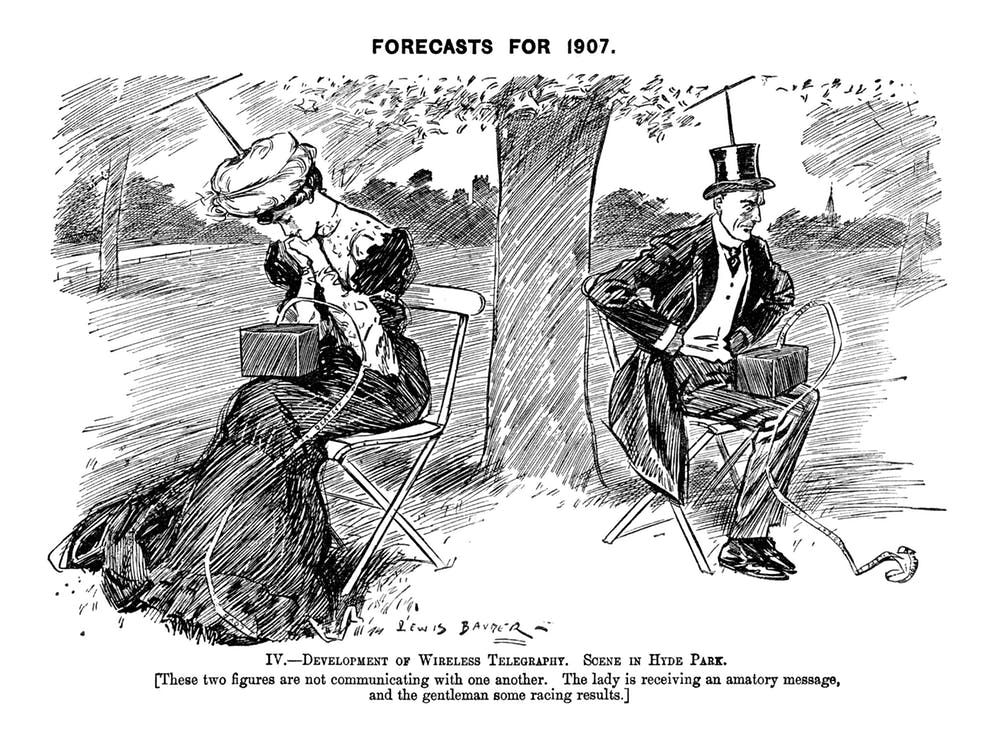

The fact that the world was getting smaller was the focus of bewildered speculation. Jack London wrote in “The Shrinkage of the Planet” in January 1900, “What a playbill has this planet of ours become! . . . The telegraph annihilates space and time. Each morning every part knows what every other part is thinking, contemplating, or doing. A discovery in a German laboratory is being demonstrated in San Francisco within 24 hours. The death of an obscure missionary in China, or of a whiskey smuggler in the South Seas, is served up with the morning toast.” Prodigy and preacher Edward Everett Hale envisioned a future where people could be shot by pneumatic tube from Texas to Georgia; what we would today recognize as Elon Musk’s Hyperloop.

I’ve spent the past couple of years immersed in magazines and fiction from the Gilded Age for book research. Beyond the grand masters of speculative fiction, who predicted atomic warfare and submarines and so much else—H. G. Wells and Jules Verne—the writers who stayed with me included establishment literary heavyweights, a canonical children’s writer, an African-American Baptist minister, and a Bengali woman who created a utopian, science-worshipping place called Ladyland as early as 1905. Their ideas ranged from wireless communication, solar power, flying machines, augmented reality, and lab-grown food to socially radical visions of a black president, women as executives in the workplace, and the animal rights movement. Though I’m still far from having a complete collection of great speculative work from this time, these are—presented in chronological order—some of the works I’ve found that shine like beacons of weird insight, works that disregarded plausibility and ended up crazy as the proverbial fox.

Looking Backward: 2000-1887 by Edward Bellamy (1888)

Looking Backward was a galvanizing bestseller that has sunk into obscurity today, though several of the stories featured later in this article were conceived as direct responses to it. Entire utopian communes, like the Oneida Colony in upstate New York, were founded because of it. Dozens of Bellamy Clubs were formed to discuss and enact the book’s ideas. Only Uncle Tom’s Cabin and Ben-Hur outsold it just after its publication. It was published at a moment when working people were exhausted by a series of recessions in the 1870s and ‘80s, then stuck with laissez-faire capitalism in the form of giant monopolies willing to violently suppress collective action.

Then-minor journalist Edward Bellamy imagined his hero awakening from a 113-year sleep to find his hometown of Boston—and the nation beyond it—transformed into a socialist paradise. Everyone works until age 45, then retires with the same comfortable income from the state. Electric light, credit cards, newscasts, and shopping malls are ubiquitous. Commercial advertising has been replaced with fine art. In this future, “all who do their best are equally deserving, whether that best be great or small.” It all sounds classically Marxist and extremely sweet.

Unveiling a Parallel by Alice Ilgenfritz Jones and Ella Merchant (1893)

Two women from Cedar Rapids, Iowa collaborated on this deliciously sarcastic novel set on Mars. The unnamed narrator, a man, travels via “aeroplane” to Mars (real planes would not take off for another ten years). He finds a lush planet that not only supports human life, but where women have equal social and professional agency as men. They vote, work as executives in business and government, have relationships out of wedlock, and otherwise seem designed to make their masculine visitor extremely uncomfortable—even as he becomes infatuated with one of them. Additionally, the Martian women gather in private clubs and special train-cars to “vaporize”: instead of smoking, they inhale a mixture of alcohol and valerian root, designed to soothe the nerves.

Besides the aeroplane and vaping, though, the story foresees the shattering of patriarchal views that would be accelerated in the Roaring Twenties. The narrator attends a festive day at which a secretive social club of women enjoy wine and song, and the next morning he is appalled when his love interest, a confident and successful banker, admits to being too hungover to leave home. At each turn, the visitor repeatedly expresses his unease with the enfranchised state of women on Mars, until his guide remarks with a smile, “Do you know, your loyalty and tender devotion to individual women, and your antagonistic attitude toward women in general—on the moral plane—presents the most singular contrast to my mind!”

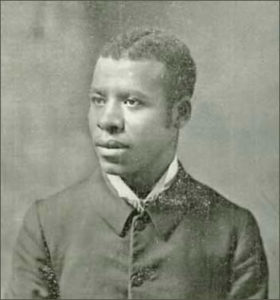

Imperium in Imperio by Sutton E. Griggs (1899)

Baptist minister Sutton Griggs self-published this lively novel and sold it door to door, until its merits were recognized and it became famous. Imperium in Imperio—literally “empire within an empire”—conjures an alternate reality focused on a secret nation-state within the United States, led by a black president.

It begins with a neat Dickensian conceit: the story follows two childhood friends, educated at the same excellent school but separated by fortune, education and skin color, forced to choose between assimilating into an oppressive society or mounting a revolution. The light-skinned, charismatic Bernard Belgrave is a mesmerizing orator: “His voice was sweet and well modulated and never failed to charm. Admiration was plainly depicted on every face as he proceeded. He brought to bear all the graces of a polished orator, and more than once tears came into the eyes of his listeners.”

The dark-skinned Belton Piedmont, meanwhile, is even more persuasive as a thinker and leader; when he speaks, “[t]he whole audience seemed as if in a trance. His words made their hearts burn, and time and again he made them burst forth in applause.” As Bernard starts a militant movement to take over the state of Texas, Belton advocates for peace and cooperation—jeopardizing his life in the process. The book was one of the earliest to envision the complete dismantling of predominantly white social institutions.

“Within an Ace of the End of the World” by Robert Barr (1900)

The Scottish-Canadian novelist Robert Barr published this tale in McClure’s magazine in 1900, predicting lab-grown food and electricity generated from the wind. It opens as a young scientist, a protege of a wealthy English aristocrat, gets to his feet at a banquet with a shocking revelation: “Gentlemen,—I was pleased to hear you admit that you liked the dinner which was spread before us tonight. I confess that I have never tasted a better meal . . . I have, therefore, to announce to you that all the foods you have tasted and all the liquors you have consumed were prepared by me in my laboratory.” It’s an ingenious pitch—for the scientists wants the rich men present to invest in his invention. In a couple of years—the story is set in 1904, barely projecting into the future—agriculture has ceased to exist, except as a hobby.

In Barr’s world, the process behind lab-grown food results in the depletion of nitrogen from the atmosphere. There is suddenly too much oxygen; people breathing it go joyously insane, and fire erupts and spreads uncontrollably. A group of somber young men at Oxford see what’s happening and survive the apocalypse by hunkering down in an iron house. At the end of the tale, they’ve managed to cross the Atlantic—encountering no other living creature on the journey—and traverse a melted, buried version of New York City startlingly similar to the final frame of Planet of the Apes. The first sign of life they detect is at Vassar, where a coterie of women also went into hiding and survived; the two groups repopulate the earth in their own, apparently perfect combined image. “It is doubtful if universal peace could have been brought to the world short of the annihilation of the jealous, cantankerous, quarrelsome peoples who inhabited it previous to 1904,” Barr’s narrator concludes.

Sultana’s Dream by Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain (1905)

Raised Muslim in colonial Bengal, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain wrote, taught, and campaigned tirelessly, going door to door to persuade other Muslim families to loosen the strict purdah that stifled women’s education. Sultana’s Dream begins with the narrator falling asleep in an armchair, upon which she is transported to Ladyland, an alternate world where women and science predominate. Female scientists capture solar power, develop laborless farming, control the weather via hot-air balloon, and travel via flying cars.

These inventions predict the future in much the same vein as other speculative stories of her day, but Hossain’s radical commentary on gender and power is what stays with the reader. The visitor to Ladyland finds men, who are kept sequestered and occupied with housework, have adjusted to their limited lives. Rebellion doesn’t interest them; by accepting their captivity and declining the rock the boat, they are fully complicit in it.

As the narrator and her friend in Ladyland remark while moving through the house, “[W]e must leave it now; for the gentlemen may be cursing me for keeping them away from their duties in the kitchen so long.’ We both laughed heartily.”

“The Machine Stops” by E. M. Forster (1909)

In between A Room With a View and Howards End, E. M. Forster published what might be the eeriest, most accurate vision featured here. It’s slightly comforting that even in 1909 there was so much anxiety about the enslaving qualities of the Internet, though in the story it’s called the Machine. Forster’s protagonist lives in an underground cell—as everybody around her does—and has a curated life of edutainment and consumption, tended to by gadgets and screens. In Forster’s words, “Few travelled in these days, for, thanks to the advance of science, the earth was exactly alike all over . . . What was the good of going to Peking when it was just like Shrewsbury? Why return to Shrewsbury when it would all be like Peking? Men seldom moved their bodies; all unrest was concentrated in the soul.”

Our central character, the pale, formless Vashti, lectures to large crowds, exchanges ideas with her peers, listens to music, lives simply but comfortably—until her son, off in his own cell, hatches a disturbing plan to see the world. He pleads with her, “Cannot you see . . . that down here the only thing that really lives in the Machine? We created the Machine, to do our will, but we cannot make it do our will now. It was robbed us of the sense of space and of the sense of touch, it has blurred every human relation and narrowed down love to a carnal act, it has paralysed our bodies and our wills, and now it compels us to worship it.” Shortly after his disappearance, the Machine itself starts behaving strangely

*

Hard to say more, other than urge everyone to read this and gawp. How did he know?

“When I Was a Witch” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman (1910)

In the decades after The Yellow Wallpaper, Gilman used fantasy to advocate for her version of a better world. In the novels Herland and Moving the Mountain, she followed male characters encountering feminist utopias (though Gilman was also a proponent of eugenics, and her fictional landscapes were only truly utopian for a chosen few). “When I Was a Witch” is something else: a slapstick short story focused on the plight of animals in New York City. Gilman believed in the humane treatment of animals, and hoped for a future where no one ate meat. Her story, silly as it is in some ways, brings home how common the sight of a horse being thwacked with a whip must have been, and on the smaller scale, the number of stray cats, restrained dogs, and birds in cages. “I was in a state of simmering rage,” the narrator tells us, when she is suddenly granted the power to make humans feel the pain of mistreated animals. The pained mews and barks of the city fall silent—our heroine has made them “comfortably dead,” the most expedient way she can think of to teach humanity a lesson.

On the last page, the witch turns her attention to the animal that interests her the most: women, who she sees as “blind, chained, untaught, in a treadmill.” Her powers, granted by Satan and not designed for white magic, run dry just before she can take action.

The Master Key by L. Frank Baum (1901)

A year after The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, Baum published this ambivalent tale of technology run amok, revealing layers of reality beyond what the eye can see. Young hero Rob tinkers with electricity in every spare moment he’s got, guided by intuition, not really sure what he’s after. After he randomly touches two wires together one day, he’s consumed by a great flash and visited by the Demon of Electricity, who bestows a series of gifts with the power to change the world. The first gift is a box of pills: each one contains enough nourishment for a whole day. Among other gifts, there’s also a “record of events,” where news from every part of the world is gathered in real time; a set of spectacles that, like an augmented reality viewer, allows the wearer to see the character of everyone he meets; and an Illimitable Communicator, a “simple device” that allows Rob to communicate with anyone, anywhere.

In the end, Rob rejects everything the Demon has to offer. “I’ve had enough of you and your infernal inventions!” he cries. Once he’s calmed down, he tells his visitor to “Go home and lie down,” insisting the world can’t handle a future full of miracles. Not quite yet.

Stephanie Gorton

Stephanie Gorton is a writer and editor in Providence. Her book about Gilded Age journalists will be published by Ecco/HarperCollins in 2020.