5 Writers Who Blur the Boundary Between Poetry and Essay

"Poets are the Hoarders of the Literary World"

There is a Bernadette Mayer writing exercise that suggests attempting to flood the brain with ideas from varying sources, then writing it all down, without looking at the page or what spreads over it. I have attempted this exercise multiple times, with multiple sources, and what I love about it—along with many of Mayer’s other 81 prompts—is that what comes out can literally take any form. The form is not dictated by the content I read, nor the rules of the exercise. The information I collect prior to writing may be entirely disparate, seemingly unrelated, but through the writing, it begins to take shape, and links are found. In the process of communicating information in a lyric way, barriers to form withheld, I am able to develop a richer portrait of what thinking really looks like.

I heard someone say once that poets are the hoarders of the literary world: collectors of facts, dates, quotes, newspaper headlines, ticket stubs, and love letters. Indeed, another of Mayer’s prompts is to keep a diary, or diaries, of such useful things. As these journal pages begin to overflow, content spilling over the borders, the writing becomes something we might not always call a poem. Reflecting on his poetry collection The Little Edges and a book of essays The Service Porch, both of which appeared in 2016, poet and critic Fred Moten said, “The line between the criticism and the poetry is sort of blurry. I got some stuff in the poems that probably could’ve been collected with the essays.”

There is a long-standing tradition of poets who have refused genre, or reinvented it, and who continue to push the boundaries of form. Here are five, but just a cursory glance into any of their work will lead you to uncover many more.

Jenny Boully

The first essay in Jenny Boully’s latest collection Betwixt and Between: Essays on the Writing Life, published last month, is a journey into two illusive linguistic temporalities: “the future imagined and the past imagined.” By positioning the reader in a space of hypothesis, Boully tests the limits of memory and lived experience, never quite allowing her reader to land on stable footing. With this linguistic trick, a redefinition of what is the personal begins to emerge.

Throughout her work, Boully is interested in reorienting the role of the reader from passive to participatory and reorienting the structure of the text from chronological to sensory. In an introduction to Boully’s work, Mary Jo Bang writes, “She uses form in a way that undercuts our every expectation based on previous encounters with poetry.” It’s no wonder that excerpts from her first book The Body, written as footnotes to an imaginary text, were included in both John D’Agata’s The Next American Essay and The Best American Poetry 2002.

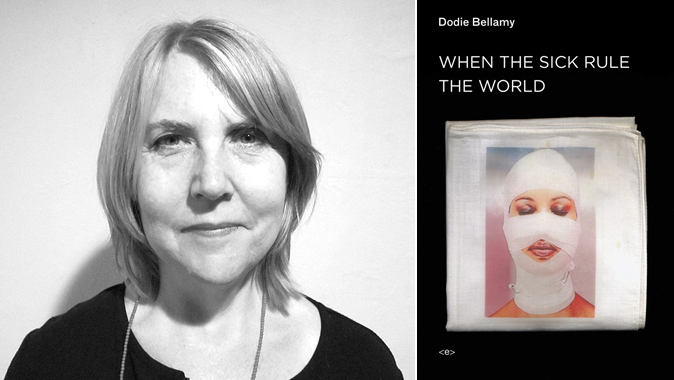

Dodie Bellamy

Dodie Bellamy is a seamstress of language. Her work stretches the definitions of narrative writing by incorporating literary appropriation, cut-ups, collage, and détournement, or the act of turning a recognizable cultural product on itself, a technique developed by the Situationist International in the 1950s. Her poetic “cunt ups” take works of the traditional poetic canon and reinvent them with a contemporary feminist voice, directly splicing the historic masculine texts with pornographic imagery. The 2013 collection Cunt Norton employs the original language of 33 canonical poets, twisting them into erotic poems as an act of love for her predecessors. “These patriarchal voices that threatened to erase me—of course I love them as well,” Bellamy wrote of the work. Her experiments began to take a more prosaic form as she desired further space for her content. “I was writing linked poems that kept getting longer and more narrative,” she said in an interview.

Due to her inventive and often hysterical treatment of language, Bellamy’s voice is engaging on any topic. The themes she tackles in her collected essays When the Sick Rule the World range from the gentrification of San Francisco, her experiences with a women’s writing group and a moving tribute to the late equally inventive writer Kathy Acker, in the form of a catalogue of the contents of her wardrobe.

Claudia Rankine

When Claudia Rankine’s Citizen won the National Book Critics Circle Award, the judges’ citation read, in part, “It’s not (just) poetry.” The prose-poetry hybrid is a current throughout her work; her previous poetry title Don’t Let Me Be Lonely was described, alongside Citizen, as “lyric essays” in the The New York Review of Books. Rankine’s work uses investigative tools of poetry to probe what it means to be human and to encourage readers to examine their personal responsibility to others. Through experiments in form, she highlights the dangers of lazy classification of people and experiences; her words in any medium provoke self-reflection.

In Citizen, a 2015 essay on Serena Williams finds a comfortable home alongside prose and list poems. With her employment of the second person throughout the collection, Rankine prompts her readers to enter into the very experiences she is describing, whether they are wholly familiar or not. As such, her approach is in equal measure confrontational and humanizing.

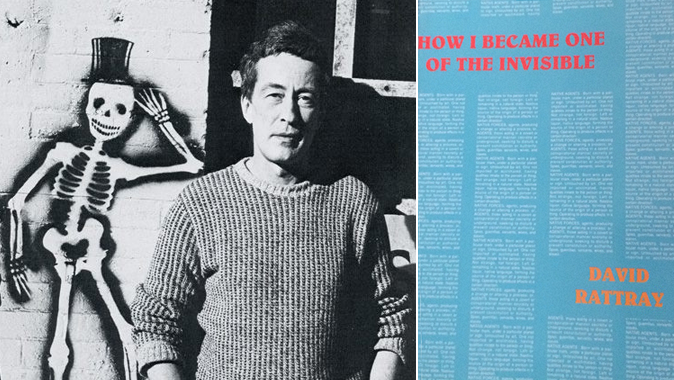

David Rattray

When the poet, critic, and renowned translator David Rattray passed away at the age of 57 in 1993, the experimental writer Lynn Tillman wrote, “He swept us away also with his ‘bad attitude,’ his insubordination to authority and to the authority of what he knew.” This was true not just in the manner he lived his life, but also how he captured life in text. A principle translator of Antonin Artaud, Rattray’s own poems display a diary-like quality: they are grand narrations stuffed full of dates, places, people.

A collection of essays and stories exploring his relationship to close friends, grief, drugs, travel, and literature called How I Became One of the Invisible was put together by Chris Kraus just before his death. Through narratives that are at once breathless and directional, and full of poetic references and quotes, Rattray reveals his deep feelings for those with whom he shared his life. “He believed people were gems, precious, and treated them accordingly,” Betsy Sussler wrote, following his passing. And so too did he treat his words, allowing us to enter into his world imbued with sensitivity.

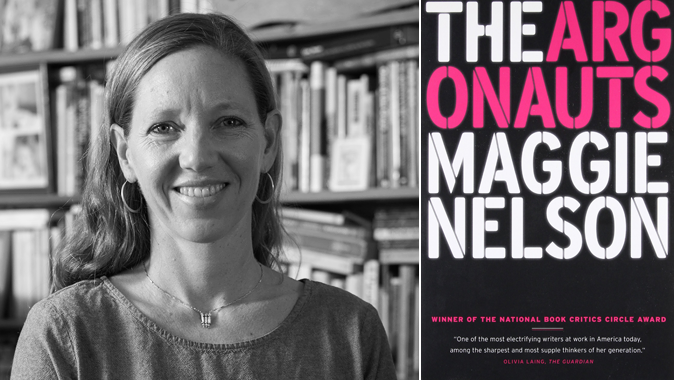

Maggie Nelson

Asked in an interview by Emily Gould as to how she decides on which genre(s) she will employ when writing a new book, Maggie Nelson replied, “Genre, for me, is determined by the unfolding of my interests, which is unknowable at a projects’ start.” Her defiance of category is not only evident in her bibliography, but in the bibliography of each book which makes it up. Bluets, which began as an investigation into the color blue and its varying manifestations throughout history, became a book of prose poems. The Art of Cruelty, a personal reflection on the employment of violence in art, became a book of academic criticism. Begun as a work of criticism, The Argonauts became a personal memoir, with its background research spilling, literally, into the margins. “I find my way to the right tone, idiom, form or set of subjects as I bumble along,” Nelson says.

It is her very adaptability of form and expression that has become one of her signature attributes, despite the literary world’s continued insistence on writerly classification, and in turn mimics the fluidity of her subjects. Hilton Als writes, “It’s Nelson’s articulation of her many selves . . . that makes her readers feel hopeful.”

Listen: Claudia Rankine talks to Paul Holdengräber about objectifying the moment, investigating a subject, and accidental stalking.

Ruby Brunton

Ruby Brunton is a nomadic writer, poet and performer. See more @RubyBrunton.