Though we too rarely hear about them today, there have been so many game-changing women in film and television that it would take volumes to cover them all. In fact, women have been involved in every aspect of moviemaking since the 19th century, when director Alice Guy-Blaché helped invent the art form itself.

But as movies hardened into big business, women found themselves increasingly pushed aside. So they did what renegades have always done: they created new opportunities out of imposed limitations. In 1953, Ida Lupino was the only high-profile female filmmaker in Hollywood. By 1956, she had turned to TV and barely looked back.

These remarkable pioneers kicked open doors while carrying heavy burdens, changing the course of our culture in ways that are still essential today. We should all share their stories. We should all know their names.

*

Alice Guy-Blaché

Photo by Austen Claire Clements

Photo by Austen Claire Clements

The French-born Guy-Blaché wasn’t just the world’s first female filmmaker; she helped midwife the birth of cinema itself. In fact, many historians believe her 1896 short The Cabbage Fairy was the very first fiction film. And she went on to make around 1,000 films of every genre, while working as a writer, director, producer, cinematographer, set designer, and casting director. Oh, and she founded and ran Solax Studios, one of America’s first production companies.

So why haven’t we all heard of her? Well, her husband turned the immensely successful Solax into Blaché Features, claiming it as his own. Though she was never less (and often more) than an equal partner, he was widely assumed to be the brains behind both ventures. As a result, when Blaché Features went bankrupt, he started over in Hollywood. But she found every door closed.

Happily, that’s not the end of her story, because she did go on to pen a fascinating, no-holds-barred autobiography, The Memoirs of Alice Guy-Blaché. Outraged that she’d been erased from a culture she pioneered, she used her fierce wit to unapologetically reclaim her credit and rewrite herself back into history.

*

Molly Haskell

Photo by Austen Claire Clements

Photo by Austen Claire Clements

The period from the late 1960s to the late 1970s is often romanticized as one of the greatest eras in filmmaking. But for whom?

In 1974, Molly Haskell—then a Village Voice film critic—offered us an alternative perspective. Her critical examination of cinema, From Reverence to Rape: The Treatment of Women in the Movies, pulled no punches. Wives, girlfriends, and mothers; prostitutes, neurotics and naïfs: these, she noted, were the overarching images of women in an overwhelmingly male industry.

From Reverence to Rape became an instant lightning rod, a film school standard, and a tremendous relief to everyone who had watched movies with a nagging sense that something wasn’t . . . quite . . . right. Throughout her seven books and thousands of reviews, she’s taught us that what we watch is only half the story. How we watch is the other.

*

Nora Ephron

Photo by Austen Claire Clements

Photo by Austen Claire Clements

Sisters Delia, Hallie, and Amy Ephron all grew up to become writers who drew on their screenwriter mother’s maxim: “Everything is copy.” But it was the eldest, Nora, who took that lesson most famously to heart. Her witty, first-person pieces for publications like New York and Esquire defined her as one of the essential forces of New Journalism, and served as the basis for bestselling books that began with 1970’s Wallflower at the Orgy.

In 1975, she and Carl Bernstein collaborated on the movie adaptation of his explosive book with Bob Woodward, All the President’s Men. And then—because everything is copy—she documented their subsequent marriage and divorce in the scandalous biographical novel Heartburn, which she and Mike Nichols turned into a movie starring Meryl Streep.

In 1990, her crystalline script for When Harry Met Sally . . . earned her an Oscar nomination and made romantic comedies de rigueur. And in the last years of her life, she gave us the Tony-nominated play Lucky Guy, the bestselling book I Remember Nothing: and Other Reflections, and the Oscar-nominated film Julie & Julia. No matter how wide-ranging the subject, the core remained the same: she honored her passions, and she understood ours.

*

Julie Dash

Photo by Austen Claire Clements

Photo by Austen Claire Clements

It took more than a decade for Julie Dash to create Daughters of the Dust, her stunning cinematic portrait of a South Carolina Gullah family descended from West African slaves. Studios were repeatedly unable to see the commercial potential in her nonlinear narrative, which elevated and honored the voices of black women in particular. And yet once she’d finally gathered funding and distribution, the finished film was heralded as a masterpiece.

Any viewing of the movie—which is currently on Netflix—will be deeply enhanced by reading Daughters of the Dust: The Making of an African-American Woman’s Film. The book includes not only her intricate screenplay, but illuminating interviews and essential background detail on the Sea Island culture captured in the film. And though she has yet to find the financing for a sequel, fans will be grateful to know it already exists in novel form. Also called Daughters of the Dust, it’s written in a beautifully evocative style that honors historic traditions while bringing the film’s past forward, to impact a new generation of women.

*

Gwen Ifill

Photo by Austen Claire Clements

Photo by Austen Claire Clements

By the time she was nine, Gwen Ifill knew she wanted to be a journalist. Even then, she once observed, she was “conscious of the world being this very crazed place that demanded explanation.”

She began as a local news reporter at the Boston Herald American, moving up until she became a White House correspondent for the New York Times. And she was reluctant, at first, to leave the Times to become a congressional correspondent for NBC News in 1994. But she went on to inspire countless viewers as—among other accomplishments—the first African American woman to host a national public affairs show, with Washington Week, and the first to moderate vice-presidential debates.

In her bestselling 2009 book The Breakthrough: Politics and Race in the Age of Obama, Ifill painstakingly reported on the ways in which a new generation of black politicians were rethinking the political process. In her characteristically even-handed style, each chapter spanned a multitude of vastly ranging perspectives, from the candidates and their opponents to their predecessors and constituents. Her interest was never in appeasing one side or the other, but in finding a rational middle space based on fairness and facts.

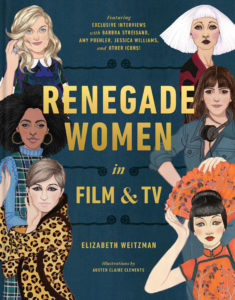

__________________________________

Reprinted from Renegade Women in Film & TV. Copyright © 2019 by Elizabeth Weitzman. Illustrations by Austen Claire Clements. Published by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.