5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week

"Offering a mouthful of nectar that tastes faintly of blood."

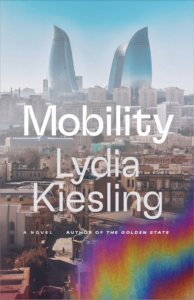

Our smorgasbord of sumptuous reviews this week includes Alexandra Kleeman on C Pam Zhang’s The Land of Milk and Honey, Naoíse Mac Sweeney on Emily Wilson’s translation of The Iliad, Jennifer Wilson on J. M. Coetzee’s The Pole, Jess Bergman on Lydia Kiesling’s Mobility, and Mae Ngai on Fae Myenne Ng’s Orphan Bachelors.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s “Rotten Tomatoes for books.”

*

“A couple of summers ago, as I drove through Oregon amid a record heat wave across the Pacific Northwest, I pulled over at a trailhead to eat a plum. Wildfires were burning, temperatures hovered around 100 degrees and the pine forest in front of me had been rendered ghostly, the edges of everything lost and faintly browned by smoke. It was a shock, then, to bite into the fruit and taste its disruptive sweetness, how fresh and pure it was in spite of the surroundings. It was the sort of thing that tears the mind and body in opposite directions—and as we face down a moment increasingly dominated by environmental crisis, this may be the ambivalent flavor of our future: sweet and bitter and full of contradiction. C Pam Zhang’s second novel…dwells with keen intelligence and rich insight at this nexus of food, pleasure, privilege and catastrophe, offering a mouthful of nectar that tastes faintly of blood … Lauded for the lean, taut prose of her debut, a historical novel following two orphaned siblings through Gold Rush California, Zhang veers unabashedly here into the decadence of language, a surplus of sensory texture and figuration … There’s an ornateness to this prose that is missing from much contemporary fiction, which is arguably obsessed with holding the attention of a ‘typical’ reader, one often imagined to have a short attention span and an interest only in the progression of plot. Instead, Zhang serves up delicacies one after another in quick succession, like in a multicourse tasting menu, resulting in a sensation of over-fullness that begins at last to turn the stomach—but this, too, is part of the author’s plan. For although the novel functions, at first, as a celebration of pleasure, of the salvage and redemption of the sensual, of the lost muchness of a world attenuated by exploitation of all kinds, the final movements call the virtue of such luxuries into question.”

–Alexandra Kleeman on C Pam Zhang’s The Land of Milk and Honey (The New York Times Book Review)

“The most interesting question about Wilson’s new translation is not whether hers is a feminist Iliad (however this is defined) but whether it is the definitive Iliad for our times. My answer is yes … Wilson has forged a poetic style in English that captures the essence of Homeric Greek…Eschewing rhyme, she has arranged her verse into a loose iambic pentameter, allowing it to spill over to occupy some 4,000 more lines than the original poem. On the page the metricality of Wilson’s verse is lost—the rhythm comes alive only when you read aloud, the words whistling up the windpipe, animating the tongue and striking the ear. No other translation communicates the oral nature of the poem so brilliantly … Another key element in Wilson’s style is the register, poised between the high epic and the everyday. Her tone manages a sweeping grandeur without pomposity, and is both refreshingly modern and largely free of the jarring chattiness of contemporary colloquialisms … A genuine page-turner, and it is all too easy to gallop through it as one would a beach read.”

–Naoíse Mac Sweeney on Emily Wilson’s translation of The Iliad (The Washington Post)

“With The Pole, Coetzee muddies the waters of national purity with his trademark clarity. The book, written in English, originally appeared in a Spanish-language translation, with the title El Polaco, as if to leave those of us tasked with identifying ‘the original’ tongue-tied. Coetzee had done the same with The Death of Jesus (2019), releasing the Spanish translation first. It was part of his campaign to ‘resist the hegemony of the English language’ … From its title, one might expect The Pole to tangle with the particulars of Witold’s national identity. Instead, the book approaches the politics of Polishness in true Coetzee fashion: with elegant elision, at such an angle as to be almost imperceptible … While some might read The Pole as a love story that unfolds across a language barrier, it is at its heart a novel about language that can be told only through a love plot. Desire seeks out definitions, and is fuelled by that labor. Witold’s first note to Beatriz is a simple enough message, as are all the ones he sends her in the following months: ‘You bring me peace’; ‘I am here for you.’ And yet Beatriz cannot imagine Witold falling in love with her, an ‘ordinary person, not an exception at all.’ She keeps thinking it must be a misunderstanding, something lost in the fault lines opened up between the pair’s native languages. Love turns her into a translator for whom no dictionary exists other than her own racing thoughts … by the novel’s end the reader understands that uncertainty is like oxygen for the fire between Beatriz and Witold. To wonder what someone meant to say is, after all, a convenient reason to think about him all the time. Anglophone readers of Coetzee, arriving late to the concert of Beatriz and Witold, know well that frustration and fealty are perfectly compatible. Coetzee told the Barcelona-based newspaper Crónica Global that the Spanish translation of The Pole ‘better reflects my intentions’ than the original English does. As we read the book, we are, like Beatriz, left to wonder not only what the words on the page mean but if the writer might have intended to say something else entirely. What was absent in the original that could be found only in translation? The novel presents words and what we desire to say as two points on a map, as far apart as the poles. To confront the distance between them is daunting, but love pushes us along.”

–Jennifer Wilson on J. M. Coetzee’s The Pole (The New Yorker)

“By embedding crucial context in naturalistic dialogue, Kiesling is able to establish the historical conjuncture in which her book is set without resorting to dull exposition. But this formal choice is more than just a canny bit of craft; it also hints at the novel’s true subject. Recognizing the epistemological impasse that Bunny runs up against in her quest to master the industry’s inner workings, Mobility is not really about oil qua oil, but the way it is narrativized—both for good and for ill … Over the course of Mobility, Kiesling develops a critique of the fossil fuel industry’s use of women as both a shield and a source of legitimacy. This applies to women on the outside: A recurring motif is the line, supplied by industry flacks like Bunny, that it’s thanks to oil and gas that mothers can give birth in brightly lit, temperature-regulated hospitals, full of high-tech devices made from petrochemical byproducts, rather than in unsanitary sheds, the United States’ high rate of maternal mortality be damned. But it’s women working on the inside who prove to be most useful to the industry. Of course, the benefits flow both ways: On the one hand, the industry’s embrace of corporate feminism allows individual women to recast their environmentally destructive and highly remunerative work as a radical riposte to the old boys’ club. More significantly, this PR strategy plays into the narrative that a lack of diversity, not a profit motive antithetical to life, is responsible for oil’s gravest ills. In this way, reforming the energy industry’s relationship to women and other minorities becomes a metonym for reforming the industry itself … Given the destructiveness of Mobility’s final act, it’s tempting to read it as an environmentalist parable, or even an intervention. But the novel is fundamentally ambivalent about the usefulness of stories in fighting climate change … Stories, Kiesling suggests, can make us feel better about the path of least resistance, or they can prompt us to consider the cost of our familiar comforts. But given that they tend toward tidy resolution, stories are more likely to produce inertia than action on a mass scale. This makes them no match for the resources of an industry that scaffolds our geopolitical order and produces trillions of dollars in profits a year.”

–Jess Bergman on Lydia Kiesling’s Mobility (The Nation)

“In an age of democratized self-expression, you need not be Serena Williams or Prince Harry to write a memoir—or for people to want to read about your life. Not all of these first-person works are good, but more of them means that some will be good, even fascinating. Take an ever-swelling corner of the memoir market: those written about theAsian American experience. Identity, in these books, is a constant theme, but refreshingly, it plays out in all sorts of different registers…The most compelling of these create space for bigger questions—about the historical legacy of marginalization, or the nature of belonging—through the details of a particular set of lives. A recent entrant into this arena reassures me that the proliferation of first-person storytelling is yielding outstanding works. Fae Myenne Ng’s Orphan Bachelors, an aching account of the author’s family in San Francisco’s Chinatown at the tail end of the Chinese Exclusion era, is an exemplar of the historical memoir … Beyond telling her family’s story, Ng memorializes an enclave stuck in time, its demographics twisted by cruel constraints. She shows that Exclusion has a reverberating and painful afterlife that dictates the limits of inclusion: One does not simply lead to the other … The story it tells is, in one sense, simply about the aches and dramas of a single family. But in another, its scope is more deeply existential. It considers the unjust constraints that can make unhappiness feel like fate, and the role that stubborn fealty can play in helping a family, somehow, stay together … In a way, the secret that Ng reveals about this era—across fiction and memoir—is how the trauma of Exclusion is transferred from one generation to the next: the complications of true and fake family histories, the desire of the younger generation to unburden themselves of that difficult inheritance, the impossibility of actually escaping it.”

–Mae Ngai on Fae Myenne Ng’s Orphan Bachelors (The Atlantic)

Book Marks

Visit Book Marks, Lit Hub's home for book reviews, at https://bookmarks.reviews/ or on social media at @bookmarksreads.