5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week

“The novel runs on an engine that relentlessly converts suffering, usually of the inner-turmoil variety, into comedic relief.”

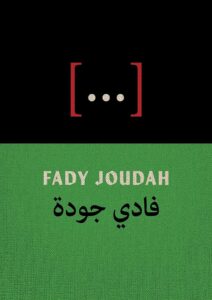

Our cauldron of commendable reviews this week includes Dwight Garner on Blake Butler’s Molly, Lauren Michele Jackson on Percival Everett’s James, Eman Quotah on Fady Joudah’s […], Emily Witt on Lucy Sante’s I Heard Her Call My Name, and Hannah Gold on Alexandra Tanner’s Worry.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s home for book reviews.

*

“It’s an atrocity exhibition. Butler taps a vein of garish and almost comic malevolence that keeps flowing … It’s a disordered book, almost Lovecraftian at times in its airless luridness. By the end, the writing has become both tedious and odious. But the first 125 pages or so are electric and sharply observed. These pages have a midnight sort of impact many novelists would kill to smuggle into their fiction … He is unsparing about Brodak’s flaws, but his tone is warm and sympathetic. If you squint, you can see this tell-all, train-wreck memoir as an act of love. This is true even though, as the observant writer and undertaker Thomas Lynch reminds his readers, ‘the dead don’t care’ … In some respects, they are a typical couple in their 30s. They own a decent house. Their work—writing—matters most to them both. In other respects, they are the Morticia and Gomez of the ATL, edgelords with good power cords, with a neurotic need to flee anything that evokes, to borrow from Luis Buñuel, the discreet charm of the bourgeoisie … It is all so much that, near the end, when Butler’s suffering, self-loathing, addiction to cliché and self-help verbiage extend to dozens of pages, you want to send him up on a Ferris wheel and strand him at the top for an hour or two … People often mistake dark things for deep things. My feelings about this book are mixed, but I won’t forget reading it. It makes you look up at the sky, fearful of what might fall out of it. That sky might seem to bellow, to borrow one of the many maledictions in Cormac McCarthy’s 2022 novel Stella Maris: ‘Your life is set upon you like a dog.’”

–Dwight Garner on Blake Butler’s Molly (The New York Times)

“In conferring interiority (and literacy) upon perhaps the most famous fictional emblem of American slavery after Uncle Tom, Everett seems to participate in the marketable trope of ‘writing back’ from the margins, exorcizing old racial baggage to confront the perennial question of—to use another worn idiom—what Huck Finn means now. And yet, with small exceptions, James meanders away from the prefab idioms that await it … Jim’s worries for his own family, a wife and child he’s left behind in bondage, must be slotted into the spaces between the boy’s gabbing, his questions, his anxieties. Jim’s sentiment toward Huck is unruly in its ambivalence: he is simultaneously protective and resentful, both relieved and uneasy when the two are separated, which in Everett’s novel they often are. With the boy in tow, Jim is mobile but stuck.

Writing himself into being means leaving Huck, and much of Huck, behind … he shows how nineteenth-century America (no less than present-day America) plays fast and loose with its most valued idioms—that is, race and money—and the material consequences, alternately grave and fortuitous, of doing so … Everett, like Twain, has often been called a satirist, but ‘satire’ is ultimately a limp and inadequate label for what Everett is up to with this searching account of a man’s manifold liberation. ‘How much do I want to be free?’ Jim asks himself early in the novel. Huck won’t be of much assistance in answering that question, and neither will Twain, for that matter.”

–Lauren Michele Jackson on Percival Everett’s James (The New Yorker)

“Palestinian American poet, translator, and physician Fady Joudah’s […], his sixth collection of poetry, takes on the inadequacy and necessity of language to convey the pain and hope of Palestinians right now … How do we read and understand these lines when we perceive them to have been preceded by a blank space? A line we cannot make meaning of because of its absence? Does the missing line suggest the tens of thousands of missing Palestinians in Gaza, buried under rubble or buried anonymously? Or the thousands of Palestinians Israel has detained, the thousands missing from their homes and families and communities? Does it suggest endless displacement? Does the silence force you to listen? …

In his collection, Joudah pushes against a challenge Palestinian poetry faces, perhaps especially poetry written in English, where poets, as much as they resist doing so, are expected to explain the Palestinian condition. The problem, of course, is not the poetry itself or the Palestinian-ness of the poet, but rather the ongoing, relentless occupation and Nakba. The feeling of being stuck in a time loop, so that a poem written in 2021 or 2014 or 2011—or 1982—about the state of occupation and apartheid, bombardment, and impending Palestinian death, reads like it could have been written today, and vice versa … Joudah’s poems and the work of these other poets cannot simply be words we read. To read the work of Palestinians now and not also speak out or take action to end the genocide, to return all Israeli and Palestinian hostages home, and help strive for freedom and liberation for all is a betrayal of epic proportions. We can’t allow ourselves to feel catharsis. We must really listen so the future we look back from is the future we want and need.”

–Eman Quotah on Fady Joudah’s […] (The Markaz Review)

“In a work that is otherwise marked by clarity and self-awareness, there is something willful about these efforts to avoid appearing ‘defensive.’ The logistics of a recent transition in upstate New York, where Sante lives, are different than they would be in a story about transitioning in Florida right now; the national context in which dozens of laws have been passed with the intention of erasing trans people from public life and hindering their access to health care goes unmentioned in her memoir, and there’s little acknowledgment that transition is not only a reckoning with the self but with a society. But it’s understandable to want to shield one’s own life story from right-wing hatred or identitarian jargon, and to downplay the entanglement of gender and government in order to focus on the quieter experience of self-inquiry, to hold it separate from the outrage cycle. Sante’s experience speaks to how transphobia gets metabolized in the mind, even for someone in a social circle in which she was rarely exposed to outright bigotry.”

–Emily Witt on Lucy Sante’s I Heard Her Call My Name (The New Yorker)

“In a much-memed scene from the second season of Fleabag, the protagonist is in the middle of confession with her hot priest crush and divulges a flash of what feels like genuine, abject self-discovery. ‘I just think I want someone to tell me how to live my life,’ she says. Now picture the Father is replaced by a Mother (or, better yet, a Mommy), the confessional by a cellphone screen in a Brooklyn apartment, the 30-something British antihero by a 20-something Jewish American woman, and you can begin to imagine the essence of Alexandra Tanner’s fabulously revealing debut novel, Worry …

Tanner works wonders with little character development (I’d call it ‘character entrenchment’) and hardly any plot (eventually, Jules and Poppy go to Florida for Thanksgiving), trusting humor to structure the story all the way through. The novel runs on an engine that relentlessly converts suffering, usually of the inner-turmoil variety, into comedic relief … Speaking from experience, Worry also nails what it was like to be a youngish media worker in Brooklyn in 2019—desperate for meaningful success in a crumbling industry, addicted to the fleeting dopamine hits of social media, online shopping and clicking ‘send’ on grant applications. It’s funnier than it should be … Some stories give you the unvarnished truth, some the varnished one. Worry is generous and wise enough to give both.”

–Hannah Gold on Alexandra Tanner’s Worry (The New York Times Book Review)

Book Marks

Visit Book Marks, Lit Hub's home for book reviews, at https://bookmarks.reviews/ or on social media at @bookmarksreads.