5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week

“What sets Taffa's memoir apart is its study of the political, racial and ancestral forces that shape a life.”

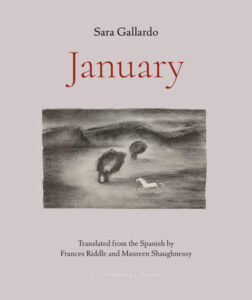

Our quintet of quality reviews this week includes Becca Rothfeld on Sloane Crosley’s Grief Is for People, Sophie Mackintosh on Martin MacInnes’ In Ascension, Lily Meyer on Sara Gallardo’s January, Kristen Martin on Deborah Jackson Taffa’s Whiskey Tender, and Heller McAlpin on Tommy Orange’s Wandering Stars.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s home for book reviews.

*

“In short, they were best friends, and Grief Is for People is a moving and much-needed tribute to this vital but often unsung human relationship. If Crosley’s descriptions of love for Russell are often dazzling and unexpected, her meditations on grief are occasionally clichéd. But bromides are par for the course when it comes to bereavement, and this, too, is part of the indignity of loss … Grief may follow a familiar path in every instance, but Russell himself was fiercely original, and Crosley paints a vivid and moving portrait of a singularity …

Not a philosophical meditation on grief but an honest account of its cruelties and contradictions. It contains no lessons, no morals and no solutions. It is not didactic. It is as messy, rollicking and chaotic as life isnot a philosophical meditation on grief but an honest account of its cruelties and contradictions … Crosley holds Russell in her heart with humor and humanity, and although she emphasizes that writing is not a consolation or an act of therapy, it is nonetheless a testament.”

–Becca Rothfeld on Sloane Crosley’s Grief Is for People (The Washington Post)

“How to comprehend the vastness of the cosmos; how to comprehend not just the mystery of our place and purpose within it, but also our own lives as we live them on earth? Martin MacInnes’s Booker-longlisted third novel, In Ascension, is an elegiac voyage through these questions, a vaulting exploration of the interplay between the micro and the macro, the human and the otherworldly … Leigh’s connection to, and reverence for, the natural world is profoundly moving. MacInnes’s descriptions are lush, almost devotional at times—‘outlines of animals burst in rapturous communication’; ‘fractal sponges and long, leaflike creatures built completely from repetition, self-similar organisms stating themselves again and again’ …

Occasionally, during sections detailing Leigh’s research and training, I wanted to return to the tense, shivering fascination of deep-sea discovery. Yet amid the recounting of preparation exercises and laboratory experiments, I came to appreciate this pacing as an exercise in readerly patience, a necessary preparation mirroring Leigh’s own. The payoff is worth it. When the mission takes Leigh into the unknowable reaches of interstellar space, we are enveloped in an ever deeper sense of interconnectedness, of patterns bigger and more beautiful than us. Human beings hurt each other, but remain drawn to each other. A clouded lake shore is as alien, and as astonishing, as anything found outside our planet.”

–Sophie Mackintosh on Martin MacInnes’ In Ascension (The New York Times Book Review)

“I got pregnant on purpose, at the time I thought was right, having wanted a baby since I was too young to bear one, and in those tired-tired months I could not stop thinking about the legions of pregnant people who were as ground down and physically miserable as me—or much more so—but not by choice. The Argentine writer Sara Gallardo’s short and hair-raisingly good 1958 novel January…focuses on one such person … María Sonia Cristoff, an Argentine fiction writer and journalist, has said that Gallardo’s writing ‘harmonizes with marginalized voices…without ever reducing them to victims,’ a compliment that, while true and serious, does not do January full justice. Gallardo, who lived a life of great choice and mobility, writes with a deep sense of kinship about the social factors—class, race, gender, religion, and rurality—that converge on poor, pregnant Nefer to take her liberty away …

Gallardo narrates Nefer’s attempts to come up with some of her own in breathless gasps of prose and brief, ellipsis-heavy bursts of dialogue. Shaughnessy and Riddle are attentive to rhythm in their translation, stacking clauses and repeating words in ways that are uncommon—and sometimes frowned upon—in English but suit the novel’s tempo … January was the first Argentine novel to deal with abortion, and it became a touchstone in Argentine feminists’ twenty-first-century fight for the right to choose. In 2020 abortion was legalized up to fourteen weeks, a restrictive deadline that still represented a major victory. Argentina’s legal code holds medical professionals to a minimum standard of abortion and postabortion care that includes ‘dignified treatment, privacy, confidentiality, autonomy’—the very things Nefer is denied.”

–Lily Meyer on Sara Gallardo’s January (The New York Review of Books)

“Taffa wrestles with why such stories have so often been silenced—and, relatedly, how the American Dream that her parents bought into came at the expense of ties to her Native culture … In its mesmerizing dive into tumultuous childhood stories and its excavation of a particular place and time, Whiskey Tender recalls Mary Karr’s now-classic memoir The Liars’ Club. What sets Taffa’s memoir apart is its study of the political, racial and ancestral forces that shape a life …

Whiskey Tender is ultimately a record of Taffa’s dual quest for belonging and a sense of self. She would eventually find harmony between these two pursuits by confronting the atrocities her people endured, pushing past the ‘silence and shame’ that permeated her family, and attuning herself to what her ancestors truly valued: ‘the beauty of the earth.’ She comes to realize ‘that we should think of the United States as one big reservation, that our ancestors’ blood and bones permeated the dust at the edge of every sunset.’ Indeed, while some reviewers have already qualified her book as a ‘Native memoir,’ Taffa’s story is in fact distinctly American, full stop, and one that a country afraid of its own history needs to hear.”

–Kristen Martin on Deborah Jackson Taffa’s Whiskey Tender (The Washington Post)

“An eloquent indictment of the devastating long-term effects of the massacre, dislocation and forced assimilation of Native Americans, it is also a heartfelt paean to the importance of family and of ancestors’ stories in recovering a sense of belonging and identity … A somewhat manic polyphonic construction that deploys first, second, and third person narration in its determination to capture the perspectives of its varied cast … Orange has a predilection for repeating words that concern endurance and survival, which results in incantatory phrases that loop and curl in on themselves, as does his narrative. His language soars as he writes of ‘the kind of love that survives surviving’ and stories that ‘take you away from your life and bring you back better made.’ He offers both as possible keys to ‘making this place more than its accumulated pain.’ Wandering Stars more than fulfills the promise of There There.”

–Heller McAlpin on Tommy Orange’s Wandering Stars (NPR)