5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week

“Her books for adults are rich and complex, revealing the stickiness of human coexistence.”

Our five-alarm fire of fantastic reviews this week includes Lily Meyer on Han Kang’s We Do Not Part, Lauren Christensen on Charlotte Wood’s Stone Yard Devotional, Lauren LeBlanc on Tove Jansson’s Sun City, Stuart Dybek on Bob Johnson’s The Continental Divide, and Sam Sacks on John McGahern’s The Pornographer.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s home for book reviews.

*

“…rendered with somber yet startling beauty by co-translators e. yaewon and Paige Aniyah Morris. Within Han’s translated body of work, We Do Not Part reads as a companion to Human Acts. While the other three novels are narrower and more domestic in focus, We Do Not Part also takes on a tremendous historical trauma. Its central subject is the suppressed memory of another mass killing, the Jeju Massacre, a yearslong extermination of suspected leftists on the island of Jeju after the Korean Peninsula was partitioned. Around 30,000 people, roughly a tenth of Jeju’s population, were murdered. Although the Korean army carried out the executions, South Korea was under U.S. military rule at the time; the United States has never admitted responsibility.

We Do Not Part bears witness—or, rather, demands that Kyungha bear witness—to these deaths. In that sense, it is a straightforwardly political novel, but that by no means requires it to be a straightforward one. It certainly isn’t a direct investigation of either Han’s life or the effect that writing Human Acts had on her. Kyungha may share some biographical details with her creator, but what matters more is her commonality with countless readers: Burdened by what she’s learned about her country’s historical atrocities, she badly—’resolutely,’ as she repeatedly puts it—wants to avoid learning more. She can’t. Fate won’t let her. We Do Not Part is as supernatural as it is historical. It’s a tale of ghosts and omens, of dreams bearing messages, of many linked kinds of haunting. The novel takes Kyungha on a terrifying journey toward knowledge, one that manages to thin the line between life and death while leaving the one between past and present impassably thick. It has as much in common with the Mexican modernist Juan Rulfo’s pitch-black masterpiece, Pedro Páramo, an eerie critique of caciquismo set in a town where everyone is dead, as it does with Human Acts. Both books ask the same question of their protagonists and their audience alike: After an atrocity, what does it mean to bear witness—and when do witnesses get to close their eyes?”

–Lily Meyer on Han Kang’s We Do Not Part (The New Republic)

“Stone Yard Devotional is the diary of a person with more days behind her than ahead, tired of trying and failing to rescue the planet from man-made destruction, wanting to make her way home. Apocalypse is not so much the plot of the book as its anchor, grounding the novel’s ruminations on forgiveness and regret, on how to live and die, if not virtuously, then as harmlessly as possible. The novel is, in many ways, an extended meditative vigil.

…

“The wrestling in this novel is with the nature and meaning of penance, atonement. Upon learning that Helen will be the one to transport Sister Jenny’s bones back to Australia, the narrator recalls their last encounter, decades ago, at a protest against logging. It’s an excruciating scene of absolution sought and denied, of quiet humiliation: ‘I told her that I was to this day ashamed of what we had done, and that I was deeply sorry for my part in it,’ she says, but it takes Helen a minute to even remember her. ‘I can see why that might have been a big … incident … for you,’ she finally replies, as intimidatingly self-assured now as she was as a child. ‘But for me, that day was nothing.’

Activism, abdication, atonement, grace: In this novel no one of these paths is holier than another; Wood is more invested in noticing the human pursuit of holiness itself. ‘Not denounced, not forgiven,’ the narrator and her sins swing in the uncomfortable uncertainty of the living. Nothing can exempt a person from this moral stain, from mortality—not even being a nun on the edge of the earth.”

–Lauren Christensen on Charlotte Wood’s Stone Yard Devotional (The New York Times Book Review)

“Though Jansson’s global fame still derives from those cheeky Moomins captured in comics and illustrated novels, her books for adults are rich and complex, revealing the stickiness of human coexistence. Jansson conveys a wry, layered empathy rooted in her Nordic traditions, informed by her queerness, and tested by her encounters with American morals and migratory habits. Thanks to a steady parade of recent reissues with introductions by Ali Smith, Lauren Groff, and others, this mature work has quietly developed a readership in the United States. A recent film adaptation of her sweet autobiographical novel The Summer Book may win new converts, but true enthusiasts will seize on the latest rerelease, Sun City, which explores an aspect of American life—the isolation of the aging—that often goes unseen.

…

“Sun City operates as a series of vignettes without a strong unifying plot—appropriate for a work about idiosyncratic humans who may share a pretty veranda lined with rocking chairs but occupy hermetically sealed worlds of their own … Americans are often said to prize their personal space, but from Jansson’s perspective, the distance among these residents is a chasm, which prevents them from connecting with others. Their private histories remain fixed in amber rather than coalescing into a collective culture.

…

“If Sun City represents Jansson’s thoughts on American society—particularly the way it treats its elders—it feels less like a quirky collection of tales, of the sort that made her famous, and more like a moral indictment. It may well be a product of extreme culture shock.”

–Lauren LeBlanc on Tove Jansson’s Sun City (The Atlantic)

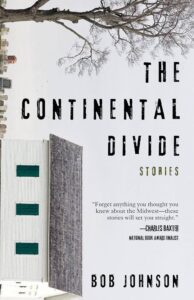

“The Continental Divide, Bob Johnson’s debut collection of 14 stories, begins with an epigraph from Jeremiah: ‘The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately wicked; who can know it?’

Epigraphs can be forgotten, if read at all, but this one continued to resonate after the tour de force title story that opens the book. As one potent story segued into another, alternative epigraphs started occurring to me. From Blake: ‘Some are Born to sweet delight/Some are Born to Endless Night.’ Johnson’s stories dwell in the latter. From Flannery O’Connor: ‘She would of been a good woman … if it had been somebody there to shoot her every minute of her life.’ That iconic story, ‘A Good Man Is Hard to Find,’ ends with the kind of violence that is a go-to in several of Johnson’s stories. Think Flannery O’Connor meets Quentin Tarantino.

There’s an entertaining cinematic quality to these narratives. Several generate physical action that, besides wickedness, is driven by rage—fights, accidents, assaults, pederasty, filicide, matricide. Johnson’s way with action and dialogue is skillful enough to be a stylistic signature. It’s taut, visceral, and yet doesn’t cross (as Hollywood can) into carnography.

…

“Johnson’s inventive, assured writing delivers what one hopes for in a first book, pages that breathe with life, and the introduction to a writer who has absorbed the echoes of iconic storytellers, but whose already identifiable voice is his own.”

–Stuart Dybek on Bob Johnson’s The Continental Divide (The New York Times Book Review)

“In McGahern’s books, Beckettian rejection collides with an impeccably classical style. He describes the jarring emptiness of Catholic ritual in prose of such sonorous beauty that it achieves the soothing rhythms of prayer.

…

“Absent in The Pornographer is the drama of lapsed faith, its narrator’s belief in any higher power having disappeared long before the story begins. Having gained distance from the raw wounds of grief (and having moved away from a direct representation of his mother), McGahern describes the aunt’s funeral in perfect accordance with her negative epiphany…Clear and precise, rhythmic without being insistent, and despite the cynicism of the imagery, strangely tender, the writing achieves a formal elegance that sacralizes its sacrilege. Fatalism feels startlingly exalted.

…

“The idea of empty time—of minutes and hours ticking by unfulfilled—haunts McGahern’s characters, lending an atmosphere of eerie philosophical dread to the realistic depictions. It is in these tableaux of monotonous waiting that Beckett’s influence is most recognizable…In The Pornographer, Beckett’s lanky shadow hovers over the narrator’s invocation of nothingness in an inner monologue that adopts the stressed cadences of liturgy.”

–Sam Sacks on John McGahern’s The Pornographer (Harper’s)

Book Marks

Visit Book Marks, Lit Hub's home for book reviews, at https://bookmarks.reviews/ or on social media at @bookmarksreads.