5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week

“Lexi Freiman shitposts from the bottom of her heart.”

Our smorgasbord of sumptuous reviews this week includes Ron Charles on Paul Lynch’s Prophet Song, Valeria Luiselli on Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo, Justin Taylor on Lexi Freiman’s The Book of Ayn, Jessica Ferri on Blake Butler’s Molly, and Mark O’Connell on Werner Herzog’s Every Man for Himself and God Against All.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s book review aggregator.

*

“If Paul Lynch’s Prophet Song were a horror novel, it wouldn’t feel nearly as terrifying. But his story about the modern-day ascent of fascism is so contaminated with plausibility that it’s impossible not to feel poisoned by swelling panic. I woke up three mornings in a row from nightmares Lynch had sown in the soil of my jittery brain … Lynch keeps the details of this national emergency vague. We hear the helicopter blades and the explosions, but mostly we see ‘the wheel of disorder coming loose’ as it’s reflected in Eilish’s eyes. And why not? The tune may differ, but every authoritarian regime sings the same lyrics: Subversive forces inciting discord, unrest and hatred against the state must be destroyed. Eilish sees that agenda from the truly domestic side …

To borrow a phrase from Hemingway, the moral bankruptcy of fascism arrives in two ways: gradually and then suddenly. But no matter how horrific events in this novel become—and they become unspeakably horrific—Eilish clings to the fantasy that this untenable situation can be managed, that the brutality of a police state can be effectively avoided or assuaged. Every page vibrates with the alarm: GET OUT! But Eilish’s faith in the future becomes a kind of curse. Every time she’s told to take her children and flee the country, it’s impossible not to relish the satisfying pity of foreknowledge, the same incredulity we feel whenever we read those sepia tales of oppressed people who tarried too long in burning regions. Lynch rips away that easy condescension. He knows free will turns out to be a political fiction once people are snagged in the gears of despotism … maybe this dystopia is exactly what’s required to rattle us from complacency, from the comforting illusion that fascism only happens far away or long ago.”

–Ron Charles on Paul Lynch’s Prophet Song (The Washington Post)

“Readers of Latin American literature may have heard one of the many versions of this story: It is 1961 and Gabriel García Márquez has just arrived in Mexico City, penniless but full of literary ambition, trying desperately to work on a new novel. One day, he is sitting in the legendary Café La Habana, where Fidel Castro and Che Guevara were said to have plotted the Cuban Revolution. Julio Cortázar walks in, carrying a copy of Juan Rulfo’s novel Pedro Páramo. With a swift gesture, as if he’s dealing cards, Cortázar throws the book on García Márquez’s table. ‘Tenga, pa que aprenda,’ he says. ‘Read this and learn.’ That night, García Márquez reads the novel in a single, feverish, sleepless sitting. He is so deeply haunted by this slim book, set in a rural village full of ghosts and echoes from the past, that he reads it again that same night, and starts memorizing it. The next day, he is finally able to begin writing One Hundred Years of Solitude…the kernel of this literary legend—the bedazzlement, the rapacious reading, the swell of inspiration — remains true …

Pedro Páramo, first published in Mexico in 1955, often produces a feverish response. Jorge Luis Borges said it was one of the greatest works of literature ever written. Susan Sontag called it one of the masterpieces of the 20th century. Enrique Vila-Matas has said that it is the ‘perfect novel.’ Roberto Bolaño’s 2666 would probably not exist without it. The book shows its readers how to read all over again, the same way The Waste Land or Ulysses does, by bending the rules of literature so skillfully, so freely, that the rules must change thereafter …

It is a story of all revolutions: the landless against the landlords, the dispossessed against the powerful. It is a story of usurpation, extraction and sexual violence. Of stealing land, settling it and exploiting it and its people. In other words, it is a story of nation-building in the Americas … The dead, tormented by lives they can no longer participate in but which their memories replay, over and over again, produce a steady undercurrent of murmurs, laments, mutterings, chatter, whispers, quiet confessions.”

–Valeria Luiselli on Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo (The New York Times Book Review)

“The novel is smart enough to know where the line is. Anna’s lacerating sense of humor is in no small part an evasive maneuver against abyssal despair. She is achingly lonely and—her skepticism of trauma discourse notwithstanding—her whole life has been defined by grief … The Book of Ayn is a story about downward class mobility. Beneath its comic surface, and for all its gleeful sleaze, it’s about the shrinking of horizons and the foreclosure of dreams, the endemic tragedies of failing democracies and middle age …

Literature is a difficult genre to neatly define, but you could do worse than start with Anna’s own notion of ‘a natural and necessary thinking-through-of-things.’ Next, maybe look to Fitzgerald’s ‘The Crack-Up,’ where he asserts the value of being able ‘to hold two opposing ideas in mind at the same time and still retain the ability to function.’ Anna, of course, is defining jokes, and Fitzgerald ‘the test of a first-rate intelligence,’ but I still feel like we’re getting somewhere. A work of literature should serve as an intellectual proving ground for both author and reader (otherwise we might as well be watching television) and all the best books are at least a little funny. This one is very funny …

Freiman’s sentences are swift and vivid, her paragraphs precision machines. Even her goofiest set pieces and illest-advised riffs feel propulsive and pull their share of narrative weight. The Book of Ayn, like Inappropriation before it, finds genuine pathos and imaginative empathy in the absolute last places you’d think to look for them or, frankly, hope to find them. Lexi Freiman shitposts from the bottom of her heart.”

–Justin Taylor on Lexi Freiman’s The Book of Ayn (Bookforum)

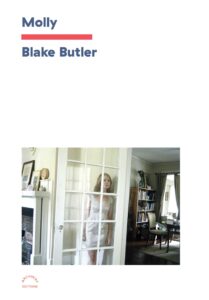

“When a writer took her own life on March 8, 2020, at age 39, her husband tweeted into the void: ‘My partner Molly Brodak passed away yesterday. I don’t know how else to tell it.’ Three years later, Blake Butler is telling the story of Molly’s death and the 10 years they spent together in a terrifyingly intense and eerily spiritual book …

Molly forces its reader to look deeply into the well of intergenerational trauma, neglect and, most of all, responsibility—the artist’s responsibility to art and themselves, our responsibility to one another as human beings … The structure of the book mimics the experience of grief: shock, devastation, seething anger and—not acceptance, exactly, but perhaps grace … Butler may not have known ‘how to tell’ Molly’s story at the beginning. He may have wished he had told it sooner, but Molly reveals that the black hole of grief, in the eye of the right beholder, spits something back out on the other side. All writing that matters is a matter of life and death. If nothing else it shows that, even in the wake of absolute horror, there is more than silence.”

–Jessica Ferri on Blake Butler’s Molly (The Los Angeles Times)

“What kind of life should an artist live? In a way this is a nonquestion, in that the only serious answer is whatever life might facilitate the production of art. But it’s a question that presented itself to me with maddening insistence as I read the German filmmaker Werner Herzog’s extravagantly titled new memoir, Every Man for Himself and God Against All. Herzog is a figure of such storied romance and such implacable charisma that to read about his life is to feel that you yourself have been going about the thing all wrong—certainly if you are any sort of artist, and perhaps even more so if you are not. As I turned the pages of Herzog’s book, and was shunted from one insane episode to the next, I was gripped by the tightening conviction that my own life was, by comparison, barely a life at all. I was not born into a country at war with the world. I have never been shot, or stabbed my own brother. I have never worked as an arena clown riding bullocks at a Mexican rodeo. I have never journeyed from Berlin to Paris on foot as a kind of magical-realist intervention to forestall the death of a beloved mentor. I have never cooked and eaten my own boot in fulfillment of a lost wager. I have never hauled a 320-ton steamship over a hill in the Amazon rainforest. I have never fallen into a crevasse while mountain climbing in Pakistan. I have never taken a trip to Plainfield, Wisconsin, with the intention of digging up the corpse of Ed Gein’s mother. I have never been bitten on the face by a rat while delirious with dysentery in a garden shed in Egypt. I have never swapped my only good shoes for a bathtub filled with fish in order to feed a film crew in the Peruvian jungle. I have never even met—let alone threatened to murder as a means of extracting a powerful cinematic performance from—the dangerous madman Klaus Kinski. And more’s the pity, I have to say—on all counts, with perhaps the exception of the rat bite/dysentery scenario.”

–Mark O’Connell on Werner Herzog’s Every Man for Himself and God Against All (The New York Review of Books)