5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week

“When Cunningham writes like himself, and not like an apostle, he is one of love’s greatest witnesses.”

Our feast of fabulous reviews this week includes Hillary Kelly on Michael Cunningham’s Day, Rachel Syme on Babra Streisand’s My Name is Barbra, Ryan Chapman on Lexi Freiman’s The Book of Ayn, Eliza Goodpasture on Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters, and Laurie Hertzel on Claire Keegan’s So Late in the Day.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s book review aggregator.

*

“Michael Cunningham is possessed by a spirit, one whom a good deal of contemporary writers find it hard to shake: Virginia Woolf walks the hallways of his novels … with new emergencies rushing by us each day, I find it harder and harder to abide literature concerned with the pandemic itself, rather than its long-tail outcomes. (Woolf’s own Mrs. Dalloway—an obvious influence on Day—benefited from being set after, not during, the flu epidemic of 1919-20.) And yet, Day is not really about the pandemic at all, and its first section, set long before anyone besides virologists had ever uttered the word coronavirus, is by far its strongest. Cunningham scatters his characters to their separate emotional exiles with an aim to bring them together at day’s (and Day‘s) end. Dispersal is his forte … Cunningham beautifully pries apart the notion of what it means to have outgrown something, to be living in the liminal space between an earlier self and a future self, to be

unable ‘to reenter the orderly passage of time.’ Day is even set on a date New Yorkers will recognize as a kind of faux spring, when, in defiance of the calendar, the earth stays hard and the flowers huddle underground … In this novel that puzzles over the elasticity of all kinds of love—familial, parental, erotic, queer, fraternal, ambiguous—I yearned for Cunningham to forget his literary peers and stick with his own special talent … When Cunningham writes like himself, and not like an apostle, he is one of love’s greatest witnesses.”

–Hillary Kelly on Michael Cunningham’s Day (The Los Angeles Times)

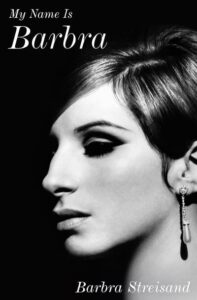

“It has been a robust year for celebrity memoirs…There’s the sob story, the gallant bildungsroman, the louche chronicle of various addictive behaviors, the righteous making of an activist, the victory lap. Streisand’s book, in its sheer breadth and largesse, attempts to be all of these things, and thus becomes something incredibly rare. Call it the diva’s memoir, an act of bravura entertainment and impossible stamina. The diva’s memoir is, by definition, a somewhat delusional form, in that its author lives in a very different world from the rest of us, and has a different sense of scale …

If something interests her, then it is interesting, full stop. In a way, she draws on an old-fashioned idea of celebrity: to be a star is to be golden, and to make everything you touch look the same. And would we want anything less? Streisand has never thought it necessary to contain herself, and there’s no reason to start now. The audio version of My Name Is Barbra is forty-eight hours long—the longest author-read memoir at Penguin Random House. It is also, I would argue, the superlative way to experience Streisand’s opus. She ad-libs at will; she refuses to say the word ‘farts.’ Sometimes she sounds like a tired bubbe, sometimes a grand dame. But she’s her best, as ever, when she’s singing….The sound is pure, exultant catharsis. It will make you believe in something, if not quite as much as the singer believes in herself.”

–Rachel Syme on Babra Streisand’s My Name is Barbra (The New Yorker)

“Putting Rand in the title of one’s satirical novel feels like a dare, or at least—in a hyper-polarized time—a provocation. The good news is Freiman has written one of the funniest and unruliest novels in ages. It shakes you by the shoulders until you laugh, vomit or both … Freiman scratches at the difference between knowing and knowingness, and how our blind spots can subsume our personality … Rife with dissatisfactions—to its credit—and with self-aware jokes and serious questions about self-awareness. Also: serious questions about jokes … Ultimately, though, the author torques her contrarianism past trolling, past knee-jerk philosophizing and past satire, alchemizing a critique of literary culture in all its ideological waywardness.”

–Ryan Chapman on Lexi Freiman’s The Book of Ayn (The Los Angeles Times)

“The feminism in this book challenges the idea that all art by women is feminist, and that all feminist art must be by or about women. It universalises, instead of essentialising. Elkin centres the book around second-wave feminism … Elkin seeks to demonstrate that any universal concept or theory about art is impossible. In a project that is fundamentally based on embodiment, there is only the individual’s reaction. The feelings we have in our bodies about what we see and experience are the truest theory—or perhaps they are beyond theory, and beyond the bounds of judgment … Instead of separating the art from the artist, she fuses the two together completely, provoking new, deeper questions about how feminism can and must evolve to engage with those who do things differently—the monsters in our midst.”

–Eliza Goodpasture on Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art (The Guardian)

“The chasm between men and women is so vast in Claire Keegan’s story collection, So Late in the Day, that her characters might as well speak different languages. (In two of the three stories, they do.) Each of these tight, potent stories takes place over just a few hours, and each explores the fraught dynamics between two people, a man and a woman … Keegan’s stories are built around character rather than action, but they never flag. The tension builds almost imperceptibly until it is suddenly unbearable. As in her stunning, tiny novels, Foster and Small Things Like These, she has chosen her details carefully. Everything means something…Her details are so natural that readers might not immediately understand their significance. The stories grow richer with each read …

All three stories pivot on a clash of expectations and desires, with women wanting independence and adventure and men expecting old-fashioned subservience and feeling baffled when they do not get it. That bafflement carries an ominous undercurrent; a threat of danger runs through each tale … they have new and powerful things to say about the ever-mystifying, ever-colliding worlds of contemporary Irish women and the men who stand in their way.”

–Laurie Hertzel on Claire Keegan’s So Late in the Day (The Star Tribune)