5 Book Reviews You Need to Read This Week

"It insists on patience as it doles out its pleasures."

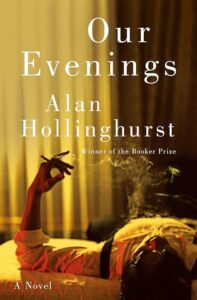

Our basket of brilliant reviews this week includes Brandon Taylor on Karl Ove Knausgaard’s The Third Realm, John Jeremiah Sullivan on Aaron Robertson’s The Black Utopians, Ed Park on Tricia Romano’s The Freaks Came Out to Write, Christopher Taylor on Anne Enright’s The Wren, the Wren, and Hamilton Cain on Alan Holliinghurst’s Our Evenings.

Brought to you by Book Marks, Lit Hub’s home for book reviews.

*

“Karl Ove Knausgaard does not write books—he writes cycles. From his six-volume masterwork of autofiction, My Struggle, to the exquisitely lyrical meditations that make up his nonfiction quartet named after the seasons, Knausgaard operates at the scale of the epic or the saga; and while his work is deeply contemporary, in mode and concern it seems to issue out of some older phase of life that demanded such a scale … These page counts are reminiscent of fantasy or science fiction novels, which also operate at an epic scale and seek to re-create within themselves a cosmic totality.

Reading these revisited scenes, one feels the potential limitations of the project Knausgaard has set for himself. These events were granularly conveyed in The Morning Star, so even seeing them from another angle might stretch a taut line to the point of breaking. But Knausgaard expands the world of the story as well, adopting a meanwhile, elsewhere approach to bring us new dramatic episodes.

The Third Realm is the strangest of the novels in the series so far, and there are genuinely scary moments in the book that I will not spoil. It feels as if we’ve crossed some boundary of plausible deniability in the books, moved beyond a time when we might have accounted for the visitations, visions and other occurrences by some rational explanation.

Certainly, it is a book that rewards prior knowledge—one of the dangers of writing a series or a cycle. But it is also one of the most genuinely suspenseful, alluring books I’ve ever read. Novel by novel, Knausgaard is replenishing some feral charge to the world. This book made me afraid of the dark again.”

–Brandon Taylor on Karl Ove Knausgaard’s The Third Realm (The Washington Post)

“Looked at from a certain surface-level perspective, the whole notion of Black utopianism can seem to entail a paradox. As the literary scholar Charles Scruggs put it more than 30 years ago in Sweet Home: Invisible Cities in the Afro-American Novel, ‘Given what we know about the position of Black Americans within a racist society, the idea of a Black utopian city may seem absurd on the face of it.’

Yet the opposite observation seems equally true. Those with the least to lose, socially and economically speaking, are often the most receptive to radical thinking on how to reorder human society, and the most fluent in wielding it, at least in the imaginative realm. To quote Aaron Robertson, in his interesting and idiosyncratic new book, The Black Utopians, ‘The apparent persistence of abysmal realities for Black people, and the certainty that there exists much more besides, is the soil from which Black utopianism emerges’…

The thing Robertson does set out most emphatically to do—to consider the question, ‘What does utopia look like in Black?’—he does in an original and compelling way. The letters from his father are among the most effective and affecting parts of the book. He seems to have realized that he possessed, in his old man’s words, a living specimen of the subject that really calls to him in The Black Utopians, not the history of Black utopias so much as the psychology of Black utopianism, a pain that can make utopian spaces not just tempting or inspiring but vitally necessary. At the book’s strongest moments, we sense in the eccentricity of its design not a ramshackle structure but the quality that, according to Robertson, utopia ‘always describes’: ‘a perpetual opening.’”

–John Jeremiah Sullivan on Aaron Robertson’s The Black Utopians: Searching for Paradise and the Promised Land in America (The New York Times Book Review)

“The Voice became many things to me: a place of drudgery and triumph and endless office politics, a writing school, a talent pool, my crucible and passport. For all its flaws, it is still the most diverse place I’ve ever worked. Eventually, I would move off the copy desk, file pieces almost weekly (a speed that alarms me now), and ultimately helm the Voice Literary Supplement. It all ended for me in the summer of 2006, when I was laid off with four other senior editors. In the aftermath, wounded but wiser, I distanced myself from the Voice. For a long time, I referred to it as the Paper That Shall Not Be Named. It meant so much to me, until it didn’t.

Perhaps I kept my distance too well. I recognize both the best and worst of my longtime employer in Tricia Romano’s excellent The Freaks Came Out to Write: The Definitive History of the Village Voice, the Radical Paper That Changed American Culture, but I do not appear in it. And though I was fascinated and occasionally shocked to read the thought-bombs of many former colleagues, my closest associates are nowhere to be found. (Romano and I overlapped; she was the nightlife correspondent, and a friendly face in the office.) At times, reading it felt like seeing photos on a realtor’s website of someplace I used to live, all Edwidgean traces erased…

Freaks charts the rise and fall of a true force in the counterculture—an improbable stab at utopia that gained unbelievable cachet, only to be brought down inexorably by some of the energies and economies it helped to pioneer. At its best, the book shows how a New York newspaper’s particular brand of journalism—a mix of personal take, zealous muckraking, and hunger for the new—had repercussions in the culture at large. If the New York Times was the paper of record, the Village Voice was the B-side you kept coming back to.”

–Ed Park on Tricia Romano’s The Freaks Came Out to Write: The Definitive History of the Village Voice, the Radical Paper That Changed American Culture (Harper’s)

“The relationship between Nell and Carmel is filled with exasperation and misunderstandings, but also affection. Putting it at the center of the novel lets Enright do several things. It gives the figure of the millennial sex novel heroine—slightly flat, by design, in Conversations with Friends—a deep, richly imagined backstory of which she’s only partly aware. It lets Enright stage scenes of intergenerational puzzlement, some funny…some complex and resonant…And it displaces male power from the focal point of the story, making Felim an ugly blur in the foreground and Phil a shadowy, mythic presence in the background…

…what’s distinctive about The Wren, the Wren has less to do with plot development or even the energy and finesse with which it handles different voices and textures than with the way it plays the movement of the story against the movement of thought and feeling. Just as Enright’s sentences are carefully worked but also close to ordinary speech, the novel is filled with time shifts and changes of perspective but also traces an emotional line that’s clear and direct. Like all of Enright’s fiction, it’s stringently unsentimental but in the end not cold.”

–Christopher Taylor on Anne Enright’s The Wren, the Wren (New York Review of Books)

“Structured like a memoir, Our Evenings is no page-turner; it moves with the heavy tread of a royal procession. It insists on patience as it doles out its pleasures. Yet Dave is a captivating protagonist, threading narrative lines as Hollinghurst skewers the hidden and not-so-hidden bigotries that define Britain …

As in his earlier books, the author perfumes his tale with eroticism, an emphasis on same-sex seduction, yet his reach is broader here, surveying a constellation of male relationships. Lovers vanish; friendships wither on the vine; mentors rarely falter; husbands hang on during tough times. Always Dave, a modern Telemachus, searches for scraps of information about his absent father.

Hollinghurst wears his influences like a greatcoat: Jacobin dramatists, Henry James and E.M. Forster in particular. But the clothes suit him as he finds Dave’s voice—and the novel’s—amid the layers. With each decade Dave tightens his grip on us, linking the bloom of queer equality and social acceptance with the canker of xenophobia. The book’s final section feels both shocking and inevitable, as Hollinghurst homes in on the values sacrificed when grievances dictate why we give and withhold compassion

Our Evenings is that rare bird: a muscular work of ideas and an engrossing tale of one man’s personal odyssey as he grows up, framed in exquisite language, surrounding us like a Wall of Sound.”

–Hamilton Cain on Alan Holliinghurst’s Our Evenings (The New York Times Book Review)