25 Essential Notes on Craft from Matthew Salesses

Rethinking Popular Assumptions of Fiction Writing

1. Craft is a set of expectations.

2. Expectations are not universal; they are standardized. It is like what we say about wine or espresso: we acquire “taste.” With each story we read, we draw on and contribute to our knowledge of what a story is or should be. This is true of cultural standards as fundamental as whether to read from left to right or right to left, just as it is true of more complicated context such as how to appreciate a sentence like “She was absolutely sure she hated him,” which relies on our expectation that stating a person’s certainty casts doubt on that certainty as well as our expectation that fictional hatred often turns into attraction or love.

Our appreciation then relies on but also reinforces our expectations.

What expectations, however, are we really talking about here?

In her book Immigrant Acts, theorist Lisa Lowe argues that the novel regulates cultural ideas of identity, nationhood, gender, sexuality, race, and history. Lowe suggests that Western psychological realism, especially the bildungsroman/coming-of-age novel, has tended toward stories about an individual reincorporated into society—an outsider finds his place in the world, though not without loss. Other writers and scholars share Lowe’s reading. Examples abound: In Jane Eyre, Jane marries Rochester. In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth Bennet marries Mr. Darcy. In The Age of Innocence, Newland Archer, after some hesitation, marries May Welland. (There is a lot of marriage.) In The Great Gatsby, Nick Carraway returns to the Midwest and Daisy Buchanan returns to her husband.

Some of these protagonists end up happy and some unhappy, but all end up incorporated into society. A common craft axiom states that by the end of a story, a protagonist must either change or fail to change. These novels fulfill this expectation. In the end, it’s not only the characters who find themselves trapped by societal norms. It’s the novels.

3. But expectations are not a bad thing. In a viral craft talk on YouTube, author Kurt Vonnegut graphs several archetypal (Western) story structures, such as “Man in a Hole” (a protagonist gets in trouble and then gets out of it) and Cinderella (which Vonnegut jokes automatically earns an author a million dollars). The archetypes are recognizable to us the way that beats in a romantic comedy are recognizable to us—a meet-cute, mutual dislike, the realization of true feelings, consummation, a big fight, some growing up, and a reunion (often at the airport). The fulfillment of expectations is pleasurable. Part of the fun of Vonnegut’s talk is that he shows us how well we already know certain story types and how our familiarity with them doesn’t decrease, maybe only increases, our fondness for them. Any parent knows that a child’s favorite stories are the stories she has already heard. Children like to know what is coming. It reduces their anxiety, validates their predictions, and leaves them able to learn from other details. Research suggests that children learn more from a story they already know. What they do not learn is precisely: other stories.

Craft is also about omission. What rules and archetypes standardize are models that are easily generalizable to accepted cultural preferences. What doesn’t fit the model is othered. What is our responsibility to the other? In his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell famously theorized a “monomyth” story shape common to all cultures. In reality, his theory is widely dismissed as reductionist—far more selective than universal and unjustly valuing similarity over difference. It has been especially criticized for the way its focus on the “hero’s journey” dismisses stories like the heroine’s journey or other stories in which people do not set off to conquer and return with booty (knowledge and/or spirituality and/or riches and/or love objects). It is important to recognize Campbell’s investment in masculinity as universal.

Craft is also about omission. What rules and archetypes standardize are models that are easily generalizable to accepted cultural preferences.

Craft is the history of which kind of stories have typically held power—and for whom—so it also is the history of which stories have typically been omitted. That we have certain expectations for what a story is or should include means we also have certain expectations for what a story isn’t or shouldn’t include. Any story relies on negative space, and a tradition relies on the negative space of history. The ability for a reader to fill in white space relies on that reader having seen what could be there. Some readers are asked to stay always, only, in the negative. To wield craft responsibly is to take responsibility for absence.

4. In “A Journey Into Speech,” Michelle Cliff writes about how she had to break from accepted craft in order to tell her story. Cliff grew up under colonial rule in Jamaica and was taught the “King’s English” in school. To write well was to write in one specific mode. She went to graduate school and even published her dissertation, but when she started to write directly about her experience, she found that it could not be represented by the kind of language and forms she had learned.

In order to include her own experience, Cliff says she had to reject a British “cold-blooded dependence on logical construction.” She mixed vernacular with the King’s English, mixed Caribbean stories and ways of storytelling with British. She wrote in fragments, to embody her fragmentation. She reclaimed the absences that formed the way she spoke and thought, that created the “split-consciousness” she lived with.

To own her writing—I am paraphrasing—was to own herself. This is craft.

5. Craft is both much more and much less than we’re taught it is.

6. In his book on post–World War II MFA programs, Eric Bennett documents how the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, the first place to formalize the education of creative writing, fundraised on claims that it would spread American values of freedom, of creative writing and art in general as “the last refuge of the individual.” The Workshop popularized an idea of craft as non-ideological, but its claims should make clear that individualism is itself an ideology. (It shouldn’t surprise us that apolitical writing has long been a political stance.) If we can admit by now that history is about who has had the power to write history, we should be able to admit the same of craft. Craft is about who has the power to write stories, what stories are historicized and who historicizes them, who gets to write literature and who folklore, whose writing is important and to whom, in what context. This is the process of standardization. If craft is teachable, it is because standardization is teachable. These standards must be challenged and disempowered. Too often craft is taught only as what has already been taught before.

7. In the West, fiction is inseparable from the project of the individual. Craft as we know it from Aristotle to E. M. Forster to John Gardner rests on the premise that a work of creative writing represents an individual creator, who, as Ezra Pound famously put it, “makes it new.” Not on the premise that Thomas King describes in The Truth About Stories: A Native Narrative: that any engagement with speaking is an engagement with listening, that to tell a story is always to retell it, and that no story has behind it an individual. Each “chapter” of King’s book, in fact, begins and ends almost the same way and includes a quote from another Native writer.

Audre Lorde puts it this way: “There are no new ideas. There are only new ways of making them felt, of examining what our ideas really mean.” (My italics.)

It is clear in an oral tradition that individual creation is impossible—the authors of the Thousand and One Nights, the “Beowulf poet,” Homer, were all engaging with the expectations their stories had accrued over many tellings.

Craft is the cure or injury that can be done in our shared world when it isn’t acknowledged that there are different ways that world is felt.

Individualism does not free one from cultural expectations; it is a cultural expectation. Fiction does not “make it new;” it makes it felt. Craft does not separate the author from the real world.

When I was in graduate school, a famous white writer defended Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (whose craft was famously criticized by author Chinua Achebe for the racist use of Africans as objects and setting rather than as characters) by claiming that the book should be read for craft, not race. Around the same time, another famous white writer gave a public talk in a sombrero about the freedom to appropriate. Thomas King, on the contrary, respects the shared responsibility of storytelling and warns us that to tell a story one way can “cure,” while to tell it another can injure.

Craft is never neutral. Craft is the cure or injury that can be done in our shared world when it isn’t acknowledged that there are different ways that world is felt.

8. Since craft is always about expectations, two questions to ask are: Whose expectations? and Who is free to break them?

Audre Lorde again: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

Lorde presents a difficult problem for people who understand that freedom is never general but always freedom for someone: how to free oneself from oppression while using the language of one’s oppressors? This is a problem Lorde perhaps never fully “solved.” Maybe it has no solution, but it can’t be dismissed. When we are first handed craft, we are handed the master’s tools. We are told we must learn the rules before we can dismantle them. We build the master’s house, and then we look to build houses of our own, but we are given no new tools. We must find them or we must work around the tools we have.

To wield craft is always to wield a tool that already exists. Author Trinh Minh-ha writes that even the expectation of “clarity” is an expectation of what is “correct” and/or “official” language. Clear to whom? Take round and flat characters. In Toward the Decolonization of African Literature, authors Chinweizu, Onwuchekwa Jemie, and Ihechukwu Madubuike complain that African literature is unfairly criticized by Western critics as lacking round characters. E. M. Forster’s original definition of roundness is “capable of surprising in a convincing way.” Chinweizu et al. point out that this definition is clear evidence that roundness comes not from the author’s words but from the audience’s reading. One reader from one background might be convincingly surprised while another reader from another background might be unsurprised and/or unconvinced by the same character.

Whom are we writing for?

9. Expectations belong to an audience. To use craft is to engage with an audience’s bias. Like freedom, craft is always craft for someone. Whose expectations does a writer prioritize? Craft says something about who deserves their story told. Who has agency and who does not. What is worthy of action and what description. Whose bodies are on display. Who changes and who stays the same. Who controls time. Whose world it is. Who holds meaning and who gives it.

To wield craft is always to wield a tool that already exists.

Nobel Prize–winning author Toni Morrison suggests in Playing in the Dark that the craft of American fiction is to use Black people and images and culture as symbols, as tools. In other words, the craft of American fiction is the tool that names who the master is. To signify light as good, as we are taught to do from our first children’s stories, is to signify darkness as bad—and in this country lightness and darkness will always be tied to a racialized history of which people are people and which people are tools. To engage in craft is always to engage in a hierarchy of symbolization (and to not recognize a hierarchy is to hide it). Who can use that hierarchy, those tools? Not I, says Morrison. And so she sets off to find other craft.

10. In his book The Art of the Novel, Czech author Milan Kundera rejects psychological realism as the tradition of the European novel. He offers an alternate history that begins with Don Quixote and goes through Franz Kafka. He offers this history in order to make a claim about craft, because he knows that craft must come from somewhere. Contrary to psychological realism’s focus on individual agency, Kundera’s alternate craft says that the main cause of action in a novel is the world’s “naked” force.

Kundera wants to decenter internal causation (character-driven plot) and (re)center external causation (such as an earthquake or fascism or God). He insists that psychological realism is no “realer” than the bureaucratic world Kafka presents in which individuals have little or no agency and everything is a function of the system. (This is also a claim about how to read history.) Only our expectations of what realism is/should be make us classify one type of fiction (which by definition is not “real”) as realer than another. Any novel, for Kundera, is about a possible way of “being in the world,” and Kafka’s bureaucracy came true in the Czech Republic in a way that individual agency did not.

Another advocate of Kafka’s brand of “realism” is the author Julio Cortázar. Cortázar is usually considered a fabulist or magical realist. Yet in a series of lectures collected in Literature Class, he categorizes his own and other “fantastic” stories as simply more inclusive realities. He uses his story “The Island at Noon” as an example, in which a character dives into the ocean to save a drowning man, only to find that the man is himself. The story ends with a fisherman walking onto the beach we have just seen, alone “as always.” The swimmer and the drowner were never there. Cortázar says this story represents a real experience of time in which, like a daydream, it becomes impossible to tell what is real and what is not. Time, fate, magic—these are forces beyond human agency that to Cortázar allow literature to “make reality more real.”

In Toward the Decolonization of African Literature, Chinweizu et al. encourage African writers to remember African traditions of storytelling. They identify four conventions from a tradition of incoporating the fantastic into everyday life: (1) spirit beings have a non-human trait that gives them away, such as floating; (2) if a human visits the spiritland, it involves a dangerous border-crossing; (3) spirits have agency and can possess humans; and (4) spirits are not subject to human concepts of time and space.

Craft tells us how to see the world.

11. The Iowa Writers’ Workshop established craft’s current focus on style and form, writes Eric Bennett, a focus which also conveniently served four related agendas: (1) it overthrew the domination of totalitarian manipulation (if Soviet) or commercial manipulation (if American) by being irreducibly individualistic; (2) it facilitated the creation of an ideologically informed canon [of dead white men] on ostensibly apolitical grounds; (3) it provided a modernist means to make literature feel transcendent for the ages [rather than tied to time and place]; and (4) it gave reading and writing a new semblance of difficulty, a pitch of rigor appropriate for the college or graduate school classroom.

In other words, it made literature easy to fundraise for, and easy to teach.

12. We have come to teach plot as a string of causation in which the protagonist’s desires move the action forward. The craft of fiction has come to adopt the terms of Freytag’s triangle, which were meant to apply to drama, and of Aristotle’s poetics, which were meant to apply to Greek tragedy. Exposition, inciting incident, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution, denouement. But to think of plot and story shape in this way is cultural and represents the dominance of a specific cultural tradition.

Craft tells us how to see the world.

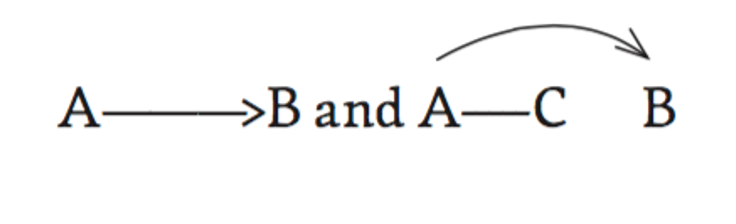

In contrast, Chinese, Korean, and Japanese stories have developed from a four-act, rather than a three- or five-act structure: in Japanese it is called kishotenketsu (ki: introduction; sho: development; ten: twist; ketsu: reconciliation). Western fiction can often be boiled down to A wants B and C gets in the way of it. I draw this shape for my students

This kind of story shape is inherently conflict-based, perhaps also inherently male (as author Jane Alison puts it: “Something that swells and tautens until climax, then collapses? Bit masculo-sexual, no?”). In East Asian fiction, the twist (ten) is not confrontation but surprise, something that reconfigures what its audience thinks the story is “about.” For example, a man puts up a flyer of a missing dog, he hands out flyers to everyone on the street, a woman appears and asks whether her dog has been found, they look for the dog together. The change in this kind of story is in the audience’s understanding or attention rather than what happens. Like African storytellers, Asian storytellers are often criticized for what basically amounts to addressing a different audience’s different expectations—Asian fiction gets labeled “undramatic” or “plotless” by Western critics.

The Greek tragedians were likewise criticized by Aristotle. In his Poetics, Aristotle does not just put forward an early version of Western craft (one closely tied to his philosophical project of the individual) but also puts down many of his contemporaries, tragedians for whom action is driven by the interference of the gods (in the form of coincidence) rather than from a character’s internal struggle. It is from Aristotle that Westerners get the cultural distaste for deus ex machina, which was more like the fashion of his time. Aristotle’s dissent went forward as the norm.

13. Craft, like the self, is made by culture and reflects culture, and can develop to resist and reshape culture if it is sufficiently examined and enough work is done to unmake expectations and replace them with new ones. (As Aristotle did by writing the first craft book.)

We are constantly telling stories—about who we are, about every person we see, hear, hear about—and when we don’t know something, we fill in the gaps with parts of stories we’ve told or heard before. Stories are always only representations. To tell a story about a person based on her clothes, or the color of her skin, or the way she talks, or her body—is to subject her to a set of cultural expectations. In the same way, to tell a story based on a character-driven plot or a moment of epiphany or a three-act structure leading to a character’s change is to subject story to cultural expectations. To wield craft morally is not to pretend that those expectations can be met innocently or artfully without ideology, but to engage with the problems ideology presents and creates.

In my research for this book, I found various authors (mostly foreign) asking how it is that we have forgotten that character is made up, that it isn’t real or universal. Kundera points out that we have bought unreflexively into conventions that say (a) that a writer should give the maximum information about a character’s looks and speech, (b) that backstory contains motivation, and (c) that writers somehow do not have control over their characters. Nobel Prize winner Orhan Pamuk, in The Naive and Sentimental Novelist, complains that creative writing programs make it seem as if characters are autonomous beings who have their own voices, when in fact character is a “historical construct . . . we choose to believe in.” To Pamuk, a character isn’t even formed by an individual personality but by the particular situation and context the author needs her for. When it’s all made up, he suggests, character is more nurture than nature. If fiction encourages a certain way that a character should be understood or read, then of course this way must influence and be influenced by the way we understand and read each other.

14. To really engage with craft is to engage with how we know each other. Craft is inseparable from identity. Craft does not exist outside of society, outside of culture, outside of power. In the world we live in, and write in, craft must reckon with the implications of our expectations for what stories should be—with, as Lorde says, what our ideas really mean.

15. Consider the example of the Chinese literary tradition, which we will get to later in the book. Western critics have generally called traditional Chinese fiction formless. Yet Chinese critic Zheng Zhenduo, who studies the Chinese novel’s historical trajectory, says one characteristic of Chinese fiction is that it is “water-tight,” by which he means that it is structurally sound. They are describing the same fiction but different expectations.

Craft does not exist outside of society, outside of culture, outside of power.

While Western narrative comes from romantic and epic tradition, Chinese narrative comes from a tradition of gossip and street talk. Chinese fiction has always challenged historical record and accepted versions of “reality.” Western storytelling developed from a tradition of oral performances meant to recount heroic deeds for an audience of the ruling class. Like Thomas King, author Ming Dong Gu, in his book Chinese Theories of Fiction, describes writing as something more like “transmission” than like “creation.” More collective and less individual.

16. Chinese American author Gish Jen claims in Tiger Writing that her fiction combines Western and Eastern craft. She makes a case for an Asian American storytelling that mixes the “independent” and “interdependent” self: the individual speaker vs. the collective speaker, internal agency vs. external agency.

The difficulty for Jen in her fiction was not in finding it a Western audience but in representing her Chinese values. As Jen writes, “existing schema are powerful.” Growing up with American and European fiction, she struggled to represent her culture and self. The kind of agency a Western protagonist has was compelling to her—she describes it almost as a seduction—being so different from her family life. Tiger Writing actually begins with Jen analyzing her father’s memoir, which is mostly family history and only gets around to himself in the final third. The suggestion is that family history, the ancestral home, their immigration to America, is exactly what defines her father, rather than any individual characteristic. Jen compares the memoir to a Chinese teapot, which unlike an American teapot is worth much more used than new, prized for how many teas have already been made in it, so that the flavor of a new tea mixes with the flavors before it.

17. “Know your audience” is craft. Language has meaning because it has meaning for someone. Meaning and audience do not exist without one another. A word spoken to no one, not even the self, has no meaning because it has no one to hear it. It has no purpose.

Chinweizu, Jemie, and Madubuike employ the metaphor of an artist’s sketch. Responding to Western critics who claim African fiction has too little description and weak characterization, they compare the relationship between craft and expectation to the relationship between a sketch and its evocation of a picture. “It perhaps needs to be stressed that the adequacy of a sketch depends upon its purpose, its context, and also upon what its beholders accept as normal or proper.” In other words, “the writer’s primary audience” may find the sketch enough to evoke the picture even if the European audience cannot. It shouldn’t be the writer’s concern to satisfy an audience who is not hers.

African fiction is written for Africans—what is easier to understand than that? Not that other people can’t read it, but, as Chinweizu et al. tell us, it might take “time and effort and a sloughing off of their racist superiority complexes and imperialist arrogance” to appreciate it.

When the Thousand and One Nights is translated into English, translators often cut stories. The Nights is a story about storytelling, full of framed narratives, stories within stories within stories. Like Chinese fiction, it is often accused of the opposite sins of African fiction—of having too many digressions and extraneous parts. Part of the necessity of abridgment is that the Nights is extremely long, and part is that different versions of the Nights include different groups of stories—it might be impossible to include every story or to know what a complete version of the Nights would even look like, as every telling is a retelling—but stories that get cut out as extraneous are never actually pointless. Author Ulrich Marzolph argues convincingly that repetition of similar stories and themes and motifs is not a failure of craft but “a highly effective narrative technique for linking new and unknown tales to a web of tradition the audience shares.” Children learn the most from stories they already know.

Similar abridgments occur in translations of traditional Chinese fiction. Again, these are often cases of translators misrepresenting the audience. In Chinese fiction, repetitions and digressions like those in the Nights are called “Casual Touches” and are a sign of mastery. According to author Jianan Qian, it takes a very good writer to be able to add “seemingly unrelated details . . . here and there effortlessly to stretch and strengthen a story’s meanings.” What is considered “good writing” is a matter of who is reading it.

18. There are many crafts, and one way the teaching of craft fails is to teach craft as if it is one.

19. Author Jennifer Riddle Harding writes about what she calls “masked narrative” in African American fiction, in which Black authors wrote to two audiences at the same time: a white audience they needed in order to have a career and a Black audience who would be able to understand a second, “hidden” meaning through context clues that rely on cultural knowledge. As an example, Harding analyzes a story by Charles W. Chesnutt about a white-presenting woman who wants to know who her mother is, and a Black caretaker who allows the woman to think her mother was white—though a Black audience would realize that the caretaker is the actual mother.

Language has meaning because it has meaning for someone. Meaning and audience do not exist without one another.

Different expectations guide different readings. “The black story had to look like a white story,” writes the author Raymond Hedin, while also speaking to a Black audience via the same words.

In other words, the plot of external causation that Kundera would like to return to never disappeared; it was simply underground. In America, coincidence and fate have long been the domain of storytellers of color, for whom the “naked” force of the world is an everyday experience. In the tradition of African American fiction, for example, coincidence plots and reunion plots are normal. People of color often need coincidence in order to reunite with their kin.

20. Adoptee stories also frequently feature coincidence and reunion. Maybe that is why I am drawn to external causation, to alternative traditions, to non-Western story shapes. Like Jen, I grew up with fiction that wasn’t written for me. My desire to write was probably a desire to give myself the agency I didn’t have in life. To give my desires the power of plot.

Cortázar calls plot, that string of causation, an inherent danger to the realistic story. “Reality is multiple and infinite,” he writes, and to organize it by cause and effect is to reduce it to a “slice.” Plot is always a departure from reality, a symbol of reality. But the power of stories is that we can mistake the symbolic for the real.

21. In Maps of the Imagination, author Peter Turchi writes about invisible conventions such as organizing prose in paragraphs, capitalizing the first letter of a sentence, assuming that the fictional narrator is not the author. These conventions become visible when they are broken. To identify them (these are tools: whose tools are these?) is the first step toward making craft conscious. Craft that pretends it does not exist is the craft of conformity or, worse, complicity.

22. Here is a convention up for debate, one in the process of becoming visible: in an essay on the pathetic fallacy, author Charles Baxter argues that setting in literary realist fiction should less often reflect the protagonist’s inner state. Baxter has seen too much rain when the hero is sad, too many sad barns when the hero has lost a child (as in the famous John Gardner prompt). In reality, rain is not contingent on emotion and objects do not change their appearances to fit people’s moods. (The Gardner prompt, to describe a barn from the perspective of a grieving father, is more about what a person in a certain mood would notice—but the point holds.) Baxter thinks realism should do more to resist story conventions and accurately represent reality.

Yet on screen, the pathetic fallacy seems widely accepted (especially if there is no voiceover to provide a character’s thoughts), and student fiction seems more and more influenced by film expectations than prose expectations.

Different expectations guide different readings.

For a few months, I read almost exclusively fiction by a trio of Japanese writers, Haruki Murakami, Yoko Ogawa, and Banana Yoshimoto. Each seems to offer a world that is very shaped by the interiority of the protagonist. In Murakami’s work, it’s a fair critique to complain that female characters seem to be who they are because the male protagonists want them to be so. In Yoshimoto’s work, characters often seem created solely for their effect on the protagonist: a psychic gives the protagonist a crucial warning, or a dying character shows the protagonist how to live. In Ogawa’s work, settings and even mathematical equations represent emotion. There are foils and mirrors and examples of how to act and how not to act and sexual fantasies and supernatural guides and exactly the right wrong partner. In truth, these worlds that seem half the protagonist’s imagination give great pleasure. There is a kind of structural pleasure that comes from seeing the pathetic fallacy played out on a grand scale. It’s not the pleasure of reality, but of what we sometimes feel reality to be, a way of being in the world.

23. Why, when the protagonist faces the world, does she need to win, lose, or draw? This is a Western idea of conflict. What if she understands herself as a part of that world, that world as a part of herself? What if she simply continues to live?

24. In Tiger Writing, Gish Jen cites a study in which whites and Asians are asked to identify how many separate events there are in a specific passage of text. Whites identify more events, because they see each individual action, such as “come back upstairs” and “take a shower,” which appear in the same sentence, as separate events—while Asians do not. Jen writes that the American novel tends to separate time into events and to see those events as progression, as development—a phenomenon she calls “episodic specificity.” At first, she believed herself to be culturally disadvantaged, as a writer, but then she found Kundera and his idea of the novel as existential rather than a vehicle for plot.

In “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” author Zora Neale Hurston identifies characteristics of African American storytelling, such as adornment, double descriptions, angularity and asymmetry, and dialect. All are things often edited out of workshop stories in the name of craft. Hurston identifies them in order to legitimize them. Craft is in the habit of making and maintaining taboos.

25. The considerations here are not only aesthetic. To consider what forces have shaped what we think of as psychological realism is to consider what forces have shaped what we think of as reality, and to consider what forces have shaped what we think of as pleasurable, as entertaining, as enlightening, in life.

Craft is support for a certain worldview.

Realism insists on one representation of what is real. Not only through what is narrated on the page, but through the shape that narration takes.

Craft is support for a certain worldview.

If it is true that drafts become more and more conscious, more and more based on decisions and less and less on “intuition,” then revision is where we can take heart. Revision is the craft through which a writer is able to say and shape who they are and what kind of world they live in. Revision must also be the revision of craft. To be a writer is to wield and to be wielded by culture. There is no story separate from that. To better understand one’s culture and audience is to better understand how to write.

__________________________________

From Craft in the Real World: Rethinking Fiction Writing and Workshopping by Matthew Salesses. Used with the permission of Catapult. Copyright © 2021 by Matthew Salesses.

Matthew Salesses

Matthew Salesses is the author of The Hundred-Year Flood, an Amazon bestseller and Best Book of September; an Adoptive Families best book of 2015; a MillionsMost Anticipated of 2015; and a best book of the season at BuzzFeed, Refinery29, and Gawker, among others. He is also the author of I’m Not Saying, I’m Just Saying and the nonfiction work Different Racisms: On Stereotypes, the Individual, and Asian American Masculinity. Adopted from Korea at age two, Matthew was named by BuzzFeed in 2015 as one of “32 Essential Asian American Writers.”