20 Ways to Be a Great Literary Citizen, According to Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

Advice on dealing with envy, gout, and rivals you'd like to put to death

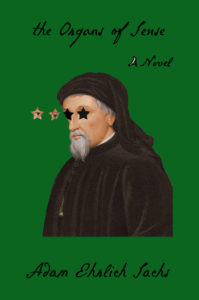

Unlike the reclusive Spinoza, the philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was a spirited participant in the Republic of Letters, not just a reader and writer but an energetic correspondent and an enthusiastic member of countless literary communities. One unexpected benefit of making him a main character in my new novel, The Organs of Sense, was becoming acquainted with his model of literary citizenship, which even today offers a great deal of useful wisdom for writers who wish to be good literary citizens.

1. Read widely…

The polymathic Leibniz read across all genres: poetry, history, law, philosophy, theology, linguistics, medicine, and mathematics, among many others.

2. …and in more than one language.

He understood German, Latin, French, Greek, English, Italian, Dutch—and also Hebrew, Chinese, and Sanskrit.

3. Workshop with friends.

Leibniz was always on the lookout for new communities with which to share his work. He presented papers to scholarly societies across Europe and toward the end of his life even sought to establish an Imperial Society of Sciences in Vienna.

4. When other writers succeed, cheer them on.

After the success of Spinoza’s Tractatus Theologico-Politicus, Leibniz sent an adulatory letter to the “celebrated doctor and profound philosopher,” praising his book.

5. At the same time, cheer on those who trash the suddenly successful writer’s book.

“You have treated this intolerably impudent work . . . as it deserves,” Leibniz wrote to Jakob Thomasius when the latter panned the Tractatus.

6. Secretly badmouth the successful writer to a considerable number of other writers.

To Johann Georg Graevius: “I deplore that a man of such evident erudition should have fallen so low.” To Antoine Arnauld: a “horrible book.”

7. Believe in your work, and yourself.

“I have solved the great problem of the union of the soul and the body,” Leibniz writes.

8. Encourage others to publish vicious takedowns of the suddenly successful writer’s book, even if many such takedowns have already been published.

“Piety urges that he should be refuted by a man of solid learning in oriental letters, such as you,” Leibniz wrote to a Professor Spitzel. Professor Spitzel, referring Leibniz to the various earlier refutations, declined.

9. Point out that the suddenly successful writer is a Jew.

“The author,” Leibniz points out to Professor Spitzel, “is a Jew.”

10. When you hear that another negative review is, to your delight, forthcoming, curry favor with the successful writer by tipping him off to it. Curry favor and enjoy the negative review simultaneously.

Pierre-Daniel Huet, tutor to the Dauphin, had been kind to Leibniz; nevertheless, Leibniz alerted Spinoza that Huet had a Tractatus refutation in the works.

11. Lend a hand at your local library.

Leibniz served as librarian in the court of the Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg.

12. But demand to be called “privy councillor” instead of “librarian.”

He also demanded to be paid a privy councillor’s salary rather than a librarian’s salary.

13. And instead of acquiring, cataloguing, and shelving books, spend most of your time in the library designing an elaborate system of windmills and pumps with which to extract water from the silver mines of the Harz Mountains. Earn the undying enmity of the Harz Mountains silver miners. Devote so little attention to the library itself that whenever the Duke asks to visit it—i.e., asks to visit his own library—you have to tell him that he can’t, that the library has not yet been put in order, but that the windmill system is nearing “such a state of perfection that I am certain that it will please the world marvelously.”

14. While still referring to the suddenly successful writer as a Jew, our Jew, or the famous Jew, obtain an unpublished copy of his next book and announce plans to write your own book on a suspiciously similar topic: The same day a mutual friend tipped him off to the contents of Spinoza’s Ethics, Leibniz announced plans to write a book called The Elements of a Secret Philosophy of the Whole of Things, Geometrically Determined.

15. Say yes, and then follow through.

Whenever possible, Leibniz said yes—to new projects, new pen pals, new writing assignments. When the Duke asked him to write a History of the House of Brunswick, Leibniz said yes.

16. If you can’t follow through, blame your gout.

Blaming gout, Leibniz foisted the History of the House of Brunswick onto his assistant, Eckhart. “The gout is just an excuse,” Eckhart wrote.

17. Become a literary citizen of the world. Spend time in a foreign literary community by hatching an insane plot to launch a new Holy War against the infidels of Egypt, a plot so deeply deranged that when you finally manage to present your plan to Louis XIV, a king who enthusiastically led France into four major wars, he’s so appalled by the idea of a new crusade that he literally responds, “I have nothing to say.” Do all of this just to live in Paris for a bit.

Bored in Mainz, eager to hobnob with the literati of Paris, Leibniz devised a crusade that he insisted to his bosses in Mainz had to be pitched to the French immediately, in person, by him, or else Europe would be subsumed by a huge war which would kill 100,000 men. The plan worked: Leibniz lived in Paris for four fun years.

18. After the early death of the successful writer, the one you’ve been completely obsessed with your whole life, argue that he, a man who once welcomed you into his home, should have been burned to death at the stake. Rethink this slightly—“I do not yet dare to decide if one has the right to sentence [him] to the ultimate punishment”—but add that he had “no conscience” and in the end wasn’t really a writer at all.

“What he knew best was to make lenses for microscopes,” Leibniz wrote.

19. Frantically skim the successful writer’s posthumous papers to make sure none of your sycophantic letters to him have survived.

One did, the one addressed to the “celebrated doctor and profound philosopher.” Leibniz panicked.

20. Attend events.

Leibniz always supported fellow writers by showing up to their events.

__________________________________

The Organs of Sense by Adam Ehrlich Sachs is out now via Farrar, Straus & Giroux.

Adam Ehrlich Sachs

Adam Ehrlich Sachs is the author of three books: Gretel and the Great War, The Organs of Sense, and Inherited Disorders. His fiction has appeared in The New Yorker, n+1, and Harper's, and he was a finalist for the Believer Book Award and the Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature. He has received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and the American Academy in Berlin, and he lives in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.