15 Great Books That Would Make Terrible Movies

From Calvino to Acker to Knausgaard, Put That Camera Down

These days, it seems every book you’ve ever heard of has also been made into a movie—or at least been optioned by some giant-eyed producer (looking at you, Scott Rudin). I ask you: is nothing sacred? Well, of course nothing’s sacred, but that doesn’t mean that there aren’t some books that really shouldn’t be made into movies—mostly because those movies would be terrible. After all, there’s a special unhappiness that comes from seeing a book you love get horribly mangled on the big screen (that 1995 adaptation of The Indian in the Cupboard broke the heart of at least one Lit Hub editor). Once you’ve seen something like that, you just can’t unsee it. To that end, here are a few books that the staff of Literary Hub begs Hollywood to please never ever make into blockbusters. (Unless, you know, you can do it right and prove us wrong. . . )

Kathy Acker, Blood and Guts in High School

Kathy Acker, Blood and Guts in High School

Adapting any book into a movie can have a literalizing effect, which proves especially tricky for surreal or hyperbolic texts like Kathy Acker’s Blood and Guts in High School, a graphic coming-of-age story replete with incest, pedophilia, trafficking, and a smorgasbord of violence both sexual and otherwise. (A representative line from early in the novel—Janey is 10, and the him in question is her father: “Janey fucks him even though it hurts her like hell ‘cause of her Pelvic Inflammatory Disease.”) Beyond the ethical and logistical challenges that attempting to film Blood and Guts would pose, some things . . . just don’t translate!

Karl Ove Knausgaard, My Struggle

Karl Ove Knausgaard, My Struggle

While the Venn diagram of Karl Ove Knausgaard fans and people who appreciate slow cinema may be close to a perfect circle, a hypothetical adaptation of My Struggle still seems like a terrible idea. Sure, plenty of films have made art from banality, but the scale of Knausgaard’s project presents a problem for this cinematic approach: Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, which follows a single mother’s cooking and cleaning in minute detail, takes place over the course of three days; My Struggle is a lifetime. And then there’s the question of how to represent Knausgaard’s mediating perspective, his essayistic digressions on art and fascism. Perhaps not even the most franchise-desperate executive in Hollywood could justify producing 20 hours of long takes in which a handsome Scandinavian bathes his children while dissecting the meaning of Hitler in affectless voiceover.

Italo Calvino, If on a winter’s night a traveler

Italo Calvino, If on a winter’s night a traveler

The problem with Calvino’s masterpiece (at least for film adaptation purposes) is that it is primarily a book about the nature and the experience of reading, and it just doesn’t seem like you can get that across without the whole “reading it” bit. The novel is the story of “you” (the reader, reading this book by Italo Calvino) trying to finish one novel and winding up reading the opening chapters of ten different ones, each with a different style, setting, and tone, each cutting off at a climactic moment, plus falling in love, sort of, with a girl who likes books. It makes for an exhilarating novel, but it would be one confusing film. On the other hand, there is a Weekend at Bernie’s-style section that I’d love to see dramatized, so here’s a free idea: someone should put on a short film festival with all the entries being adapted chapters from If on a winter’s night a traveler.

Rabih Alameddine, An Unnecessary Woman

Rabih Alameddine, An Unnecessary Woman

This novel is just so rooted in the exceptional consciousness of its narrator—the titular “unnecessary woman,” a misanthropic septuagenarian living in Beirut who has dedicated her life to translating novels no one will ever read—and so little actually happens in the present action of the film, that it would be something of a challenge to translate it (aha) to screen. Film is for action and visual beauty; literature is for internal life and memory.

Vladimir Nabokov, Pale Fire

Vladimir Nabokov, Pale Fire

Would a Pale Fire movie start with a recitation of John Shade’s 999-line poem? How would Kinbote/Botkin/King Charles’ exegesis of the poem, which he undertakes sitting in a “wretched motor lodge” facing the “very loud amusement park,” be depicted? What about the Zemblan delusions of the Prince on the run? Because Nabokov’s unreliable narrator exists (or doesn’t) in multiple dimensions as multiple characters, it’s unlikely anyone would option it (and no, I haven’t seen Blade Runner 2049 and I don’t understand how it relates to the novel, conspiracy theorists).

Junot Díaz, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

Junot Díaz, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

You’d think a bildungsroman about a kid who loves science fiction could easily make its way into film. But Diaz’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel is fundamentally a literary text that relies on the reader knowing other literary texts to understand its complexity (the title is an allusion to Oscar Wilde, the footnotes, the allusions, the Spanglish, the ending that puns on Conrad). It’s so thoroughly of the world of literature that to take it out of that context is to miss the point of the project. But if some director out there can figure out how to portray the Dominican folklore all-encompassing fuku, more power to you.

Chris Ware, Building Stories

Chris Ware, Building Stories

Graphic novels are an obvious go-to for film adaptation, but Chris Ware’s experimental Building Stories resists visual translation. Comprised of 14 standalone comics, there are over 87 billion ways of reading the book. The story itself focuses largely on interiority; pages are often filled with characters (including the house itself) reflecting in silence. The multi-perspective, nonlinear aspect does seem ripe for an anthology series, but Ware keeps the story firmly planted on the page. His compositions and attention to detail keeps readers engaged in empty rooms, and it’s hard to imagine a camera doing the same.

John le Carré, The Honourable Schoolboy

John le Carré, The Honourable Schoolboy

James Bond in Macau? Expensive, but Hollywood’s happy to pay. A broken-down spy hanging out in Hong Kong questioning his mission while everyone decent surrounding him dies? Well, the BBC certainly won’t put up the money (if they wanted to, they would have filmed this one long ago), and Hollywood, while wonderful at funding large, expensive productions, is reluctant to embrace unhappy endings unless part and parcel of a low-budget film. The Honourable Schoolboy could perhaps be adapted into an honorable miniseries, but the catch-22 remains relevant—anyone with the money to film The Honourable Schoolboy couldn’t possibly be interested in adapting it accurately, and vice versa. A Groucho Marx quote comes to mind: “I don’t want to belong to any club that will accept people like me as a member.” I wouldn’t want The Honourable Schoolboy to be filmed by anyone with the money to film it.

Mark Z. Danielewski, House of Leaves

Mark Z. Danielewski, House of Leaves

I’m pretty confident that no one will ever attempt to adapt House of Leaves for the screen. Even if you could somehow distill the essence of this rabbit-hole genre mash-up (haunted house tale, love story, satire of academic criticism all rolled up in a bulging, nightmarish package) into an intelligible three act movie, you’d still have to contend with the multiple unreliable narrators, the storylines that weave creepily and inexplicably around and through each other, the footnotes upon footnotes upon footnotes that speak to different narrative strands, the mysterious color-coded words, the sentences that can only be read in a mirror, and God only knows what else Mark Z. Danielewski buried in there. It’s a terrifying, utterly compelling book, but it would be a bloated, messy shitshow of a film.

Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

Gabriel García Márquez, One Hundred Years of Solitude

The book is a wondrous fusion of myth and history. García Márquez doesn’t just create an entire multi-generational family, he builds and lovingly furnishes a dreamscape within which they can tease out the mysteries of life and death. How are you going to cram all that into a film? You’re not; there’s just too much going on. Also: too many damn characters. How are you gonna pay for all those Buendías? The catering budget alone would bankrupt the production by the end of Day 1.

Georges Perec, An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris

Georges Perec, An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris

Perec was, by far, the life of the Oulipo party, and no amount of self-imposed literary axiom could restrain the joy of his writing—he always seemed to be having more fun than everyone else. However, this incredible little book—a compact series of quotidian observations limited to the immediate neighborhood around Paris’s unheralded (but quietly wonderful) Cathedral Saint Sulpice—would make for a terrible movie: either voice-over with Parisian streetscapes, or just relentlessly dull Parisian streetscapes. Neither of these approaches would get at the uncanny way Perec inhabited the observational eye, blurring the subjective/objective line while conjuring the slyest kind of poetry from the otherwise hyper-mundane.

Anne Garréta, Sphinx

Many Oulipian works, it seems, would not translate well to the screen. The scaffolding around which Sphinx is constructed is genderlessness; its two main characters, an unnamed narrator and a cabaret dancer referred to as A***, are never assigned gender in the text. The imaginative space left by absence of most defining physical characteristics would be lost as soon as they were embodied by actors.

Roberto Bolaño, 2666

Roberto Bolaño, 2666

Please, just don’t do this. Even if you do happen to have the grim genius of Michael Haneke combined with the epic-level hubris of Stephen Spielberg, it just won’t work. You will either amputate so much of the source material as to render it all meaningless, or you will create something so bloated and strange and personal to you as a director that it will also be meaningless. (It was attempted for stage a few years back—clocking in at five-plus hours. So.)

Renee Gladman, Event Factory

Renee Gladman, Event Factory

The city of Ravicka is surreal and absurd—its physical presence seems to slip away while it’s constructed. The narrator, a “linguist traveler,” is fluent in the native language but unable to communicate. As she tries to better understand the city—meeting natives, going to events, searching for the city’s center—she finds herself pushed further to the outside. So much of the story is centered around disorientation, a feeling that would be lost once you tried constructing a set of Ravicka.

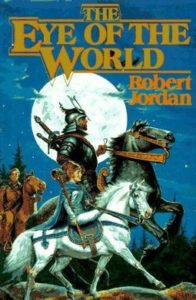

Robert Jordan, The Wheel of Time series

Robert Jordan, The Wheel of Time series

While the Wheel of Time series would arguably make for better television than George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones series, given that it is actually finished, it is still virtually unfilmable on either the big or small screen. The minimal presence of magic is what makes Game of Thrones even remotely adaptable, and Robert Jordan’s books are all about the magic, with one of the most thoroughly developed magical systems ever found in fantasy literature. The sprawling cast of characters, numerous settings, epic battle sequences, and hilariously gendered magic (men have to control their raging magic, while women have to surrender to it) all make us root for keeping this 14-book series off our screens and firmly in our imaginations.